This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The world of tidily ordered forms is a convenient fantasy. The real world gloops and glops. Here and there, it bulges. It sags. It was once considered modern to architect this chaos into order, to machine the wet muck of existence into clean lines and hard edges. That is not the modern of Gaetano Pesce, the Italian-born industrial designer–artist–architect–prophet, who has been plying his alternate vision in resin, foam, fabric, and polyurethane for more than half a century. These days, he does his conjuring out of a pungent, hard-candy-colored studio in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. On a day this past July, just before the monthlong annual summer holiday that is an Italian nonnegotiable even for an Italian who has spent four decades in New York (somehow never losing his gravelly Italianglish), Pesce was holding court there for a procession of gallery swans, museum factotums, and press attachés who had come to discuss the various Pesce retrospectives and shows around the globe.

Court is a comfortable posture for Pesce, who is imperial in his bearing and imperious in his pronouncements. An audience with the man is an opportunity for oratory, as he makes his argument against the rigid, linear world the rest of us live in unquestioningly. “Horrible,” says Pesce, gesturing vaguely at the concrete-and-glass buildings outside his window. “International Style” — the reigning aesthetic of design since the 1930s, meant to mimic the efficiency of machines, and what most of us most often associate with the word modern — “is a horrible way to make architecture. Architects don’t know that they do something that is an image of non-freedom.”

In here, freedom (according to Pesce) reigns. Your path may be blocked by a lipstick-red polyurethane foot the size of a motorbike or a resin bookcase in the shape of its creator’s face. In an upstairs archive, rows and rows of vases in lollipoplike resin stand sentry, the accessible souvenirs and satellites of Pesceworld. Major pieces, like that face bookcase or that foot, will run you $180,000 and up. Presiding above it all is Pesce himself, an imp in Issey Miyake, delighting in his creations, wonky and Wonka. Which makes him sound a bit more benign than he is. He’s a bomb thrower, a “prince of disorder,” in the words of Glenn Adamson, a prominent Pesce scholar. “Gaetano goes toward trouble,” says his friend and champion Murray Moss, who helped popularize Pesce’s work in the U.S. at his influential Soho design store, Moss.

Who else would propose to an Italian company that it make ashtrays in the shape of Christ’s crucified hand so you could tap your ashes directly into His bloody stigmata? (It was 1969; the company declined.) Or make models out of raw meat for an exhibition at the Louvre, then let them putrefy until the museum was overwhelmed by the smell? “There are lots of my colleagues who do decoration or nice things,” he says. “I don’t care about that.”

In the world of design — not to say decoration — not many names break through to broad public consciousness. You may know Charles and Ray Eames, Mies van der Rohe, Gehry, Noguchi. No rapper has yet name-checked their Pesce in a verse, though if you know what to look for, you’ll have noticed that KAWS has a Pesce, as does Urs Fischer, as does Selling Sunset’s Christine Quinn, and that one of his armchairs recently made a cameo on the new Gossip Girl. And then there are the retrospectives: one coming to Shenzhen, China; another in Genoa; an exhibition in Aspen. Here in New York, a show of new pieces opens this week at the Salon 94 gallery, which has represented him, and directed Pesces into important apartments and collections, for several years.

At 82, Pesce has lived long enough to see his work lauded as the harbinger of the “new domestic landscape” and derided as dated and sexist; even as it has been welcomed into every major design-museum collection, to his acolytes, it is underappreciated and undervalued. The pendulum swings, swings, swings. But if Donald Judd and Pesce represent two extremes of contemporary design — monasticism and mishegoss — we are very much in the throes of a Pesce moment. His fervid energy, his experimental daring, and his celebrations of error and uncertainty all make him look more and more like a visionary of our chaotic, cheerfully toxic present. “You would have to call him pre-digital,” says Kathryn Hiesinger, a senior design curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art who curated a show of Pesce’s work there in 2005, emphasizing his love of handwork and craft over internet-age perfection — which has come back around. The taffy colors, organic forms, and plasticky materiality of so much contemporary design, crafted by creators decades younger than Pesce and disseminated everywhere on Instagram, owe much to his influence as our éminence gloop. “It is so right now,” says designer Katie Stout, whose squidgy organic forms suggest Pesce’s and who calls him an inspiration. “The internet is obsessed with slime and anything adjacent to slime.”

For those who follow in Pesce’s bright shadow, his cheerful sacrilege is an invitation to go wild. “I feel like there’s a moment when everyone discovers that work in art school. It’s permission to make something really messy and then say that it’s done,” says Misha Kahn, another young Brooklyn designer whose furniture is sometimes compared to Pesce’s. “When you’re first trying to bust out of a bubble of rigidity, it’s a magical world to stumble upon.”

Pesce was born in 1939 in La Spezia on the Ligurian coast. His father, an officer in the Italian navy, was killed in World War II, and his mother raised Gaetano and his two siblings with the help of her extended family in Padua and Este and her husband’s in Florence. As a student, he was drawn to the arts — “Conversations about music and art,” he told Marisa Bartolucci, one of his biographers, “helped us to survive.” He revered Dalí and Duchamp and was drawn early and enduringly to experimentation, co-founding in 1958 the artists’ collective Gruppo N in Padua, one of a number of coteries devoted to artistic “research.”

After deciding “architecture was the most complex of all the arts,” he enrolled in architecture school in Venice but bridled at its rigidity and traditionalism. It wasn’t the right kind of modern for him, nor did he want to be constrained by just one métier. “When I finished the school of architecture, I realized that nobody taught me materials from my own time,” he says. “So I sent a letter to chemical companies to ask if it was possible to visit them. And two answered. I went and I saw incredible things.” It inaugurated an ongoing investigation into new materials like polyurethane foam and resin — gooey, pliable, light refracting, but indestructible. “Resin is better than glass,” he tells me. “You work today; tomorrow, it’s ready.” (He eventually did extend his experiments to glass, but he tweaked the technique; he demanded the development of a gun with which to shoot molten glass into a roaring furnace.)

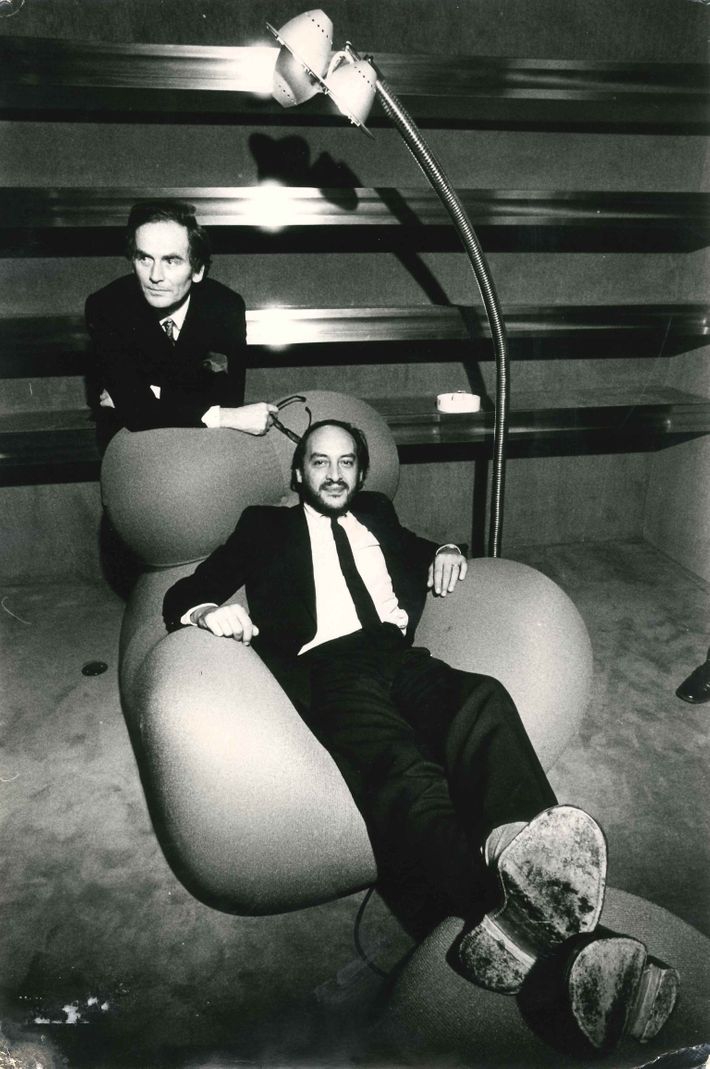

Italy in the 1960s was the crucible of innovation in industrial design, the ferment that produced Gae Aulenti and Joe Colombo. Pesce and another designer, Milena Vettore, set up a small studio in Padua and got to work. A meeting with Cesare Cassina, the furniture manufacturer, led to an ongoing collaboration, which allowed Pesce the freedom to experiment and produce, in small editions, some of his most influential works. (Vettore died in 1967.)

The world was watching. “The emergence of Italy during the last decade as the dominant force in consumer-product design has influenced the work of every other European country and is now having its effect in the United States,” wrote Emilio Ambasz of the Museum of Modern Art, introducing the 1972 exhibition of Italian design, “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape,” that brought Pesce’s work to the U.S. (Pesce’s contribution to the show was the “discovered” plans of “a small subterranean city, belonging to the epoch known as ‘The Period of the Great Contaminations’; location: Southern Europe [Alps],” which he had purportedly unearthed, alongside a short film documenting its inhabitants. The brief biography of Pesce in the catalogue describes an omnivorous artistic practice, including “silk-screen, programmed art, kinetic art, serial art, assemblage and bricolage, film, audiovisual presentations, and multimedia events involving light, movement, and sound.”)

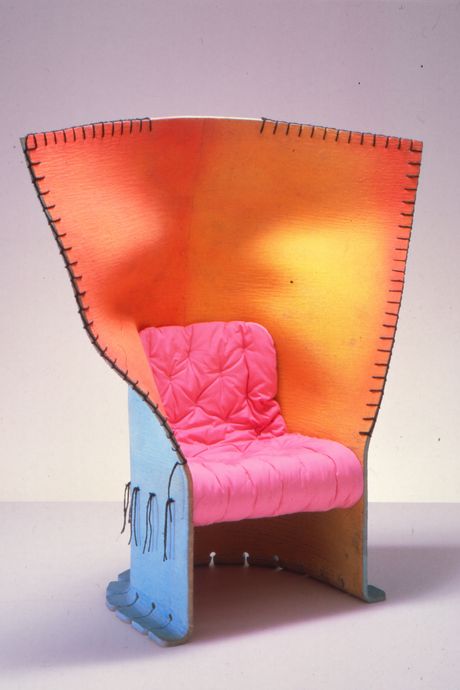

Pesce spent the ’60s and ’70s living and lecturing all over Europe, with stops in Helsinki, London, and Paris. He thrilled to the idea that furniture, in addition to being functional, could be narrative, polemical, transformational. You could literally bring a message home. He didn’t shy away from the political and had an appetite for heresy: Much of his earlier work plays with Catholicism, like the Golgotha table (1972), a tomb-shaped slab named for the hill Christ was crucified on, which drips with red “blood” — and drips, in a very Pescean touch, upside down. There are also Golgotha chairs made of resin-soaked fiberglass cloth, as if the Shroud of Turin had been freeze-dried. “It’s an incredible way, a new way, to tell a political statement,” he says. “Not through a paper, not through a movie, not through an article, not through a book, but through a chair. Why is important? Because the chair goes in each family, and someone who wants to understand, they understand that chair has a message.”

Pesce’s messages ring differently in different ears. One of his most famous pieces, the Up 5 (Donna) (“woman”) or Mamma chair, is, essentially, an upholstered foam woman, a buxom, feminine figure whose sitter nestles in her lap. Mamma’s ottoman (technically Up 6) is a round ball attached to her by a (umbilical?) cord: mother’s little ball and chain. Pesce says he intended it as a statement on the lack of freedom allowed to women, which is not to say women themselves have always seen it that way. In 2019, on the occasion of its 50th anniversary, a giant version of the chair riddled with arrows, in a Saint Sebastian touch, was installed in Milan for the city’s design fair, and an Italian feminist group protested it. “Some say it is a sex symbol,” Pesce says. “Others say this is the symbol of the mother. For me, it is a symbol of the woman victim of prejudice.” Any offended sensibilities or alternate interpretations don’t bother him. “It’s not necessary that everybody understands,” he says. “When I was going to school, I would say that, me, I understood 50 percent of what they were saying.” In any case, it hasn’t hurt Mamma’s ubiquity much. Gilberto Negrini, the CEO of B&B Italia, which produces the chair (it was re-introduced in 2000), says it is among the company’s best-selling armchairs and got a major boost from its semi-centennial. “We have created a second mold to be able to fulfill orders,” he said recently, “and a third one is about to arrive.”

In 1980, Pesce moved to New York to begin teaching at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and has lived and worked here ever since. (For a while, he also had a home in Bahia, Brazil.) “I had the impression that New York was decaying, declining,” he says. In response, he created a cartoonish sofa with blocky pillows representing buildings and an orange semi-circular sun descending behind them to be called Sunset on New York. “But then I realized that it was not declining,” he says. “I did the sofa anyway. The title is Sunset in New York.”

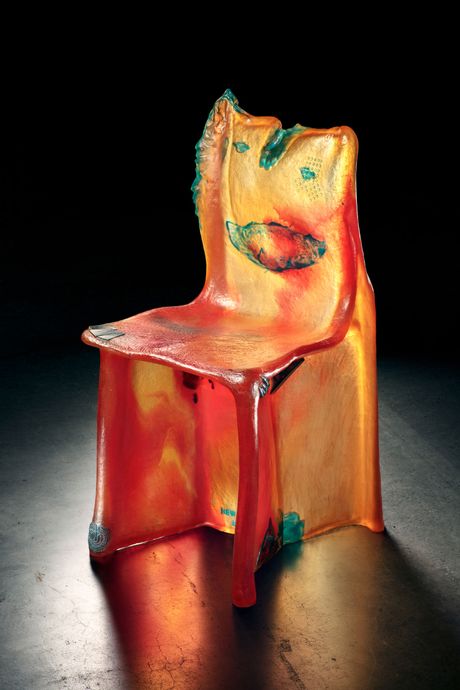

Once he’d had that epiphany, Pesce never left. “There is not a better city,” he says. It is “a very powerful place for information, for understanding the time, the reality.” New York brought a bit more jollity to his work. His Pratt chairs (1984) added a zany entropy to his process: Although the mold for each one is the same, the composition of the resins used for the initial run of nine was variable, making each goopily unique. (The first in the series was so soft that it collapsed.) Many are embedded with a daffy smile. “Some people ask me, ‘Why you do things that are smiling?’ ” Pesce says. “I say, ‘Because we need to transfer something that is positive and not tragedy.’ People, they have already a lot of tragedy.” That transfer has been positive for Pesce, too. New editions of the Pratt chair are now among his most sought-after pieces and go for around $30,000 — if you can get one.

Pesce’s renown continued to grow in the States, as did his commissions. In 1993, he designed an “organic building,” in Osaka, Japan, whose exterior is studded with live plants, slyly anticipating the “green” architecture of today. In 1994, he was commissioned to design the cutting-edge, open-plan, hot-desk headquarters of the advertising agency Chiat/Day, where employees were given loaner laptops and mobile phones and were asked to keep their personal effects in lockers. Pesce’s preoccupations with organicity and egalitarianism seem prescient now but were a matter of heated debate back then. (“We must pierce the totalitarian façade!” he yelled to his collaborators on the Chiat/Day project.) Critics were entranced. “It is a remarkable work of art,” wrote Herbert Muschamp in the New York Times. He was wowed by Pesce’s brightly colored resin floors, the plastic chairs, all evidence of a “giddy, even clumsy, yearning to kick off the dust and embrace a future as yet unrevealed.” Muschamp mused, “Who cares if we get lost, meet a dead end, run out of gas? At least no one will die of boredom.” As it turned out, workers didn’t like it much (one former employee compared it to “working inside a migraine”), and the agency cleared out in 1999. Relics from the space still regularly turn up at auction and on 1stDibs, where a door covered in toy cars and with a drippy resin handle can be yours for $7,900.

Not everyone thrills to the throbbing energy of a Pesce interior. But those who do, do. Ruth Lande Shuman, who met Pesce at Pratt, where he was her master’s-project adviser, commissioned him to redesign her entire Park Avenue apartment around the time of the Chiat/Day offices, after fretting that its “Miesian” (as in van der Rohe) style didn’t reflect her personality. (She fretted about it partly because Pesce came to dinner and told her so.) The apartment, scarcely altered since, is a shrine to Pesce. “It’s a joy every single morning,” she told me, “to wake up and feel supported by this energy, this energy of ideas and color.”

“Her apartment makes Pee-wee’s Playhouse look as anodyne as Charlie Rose’s set,” this magazine wrote in 1997, finding it “the perfect foil to the currently voguish minimalist-mausoleum look.” The mood was already shifting, according, at least, to the great man himself. “Slowly,” Pesce told an interviewer at the time, “the world catches up with Pesce.”

These days, the world has caught up with him. It is Pesce who has outlived most of his contemporaries, colleagues, and rivals, Pesce who is around to greet new generations of fans, riding the wave of another boom. (“How is he still alive using all this toxic material for so long?” wonders Stout. “Until now, I’m pretty good,” Pesce tells me. “And I don’t use masks, I don’t use anything. Sometimes we have someone coming from the City of New York, they make inspection, we receive a fine, et cetera, et cetera. If you put the resin in the bathroom, in the drain, disaster. But if you use the material with respect, is not a problem.”)

The introduction of affordable, licensed Pesce resin pieces — as opposed to his studio-made artworks — has opened up his oeuvre to a much larger clientele. Two years ago, Fabiana Faria and Helena Barquet began carrying these accessible, commercially produced items at Coming Soon, their Lower East Side design shop. They had sourced Pesce pieces for interior-design clients and loved his work but weren’t sure how it would be taken by a less learned customer. “We thought that maybe the price point would be a little too much for people,” Faria says. “They’re, like, weird looking.” But in fact Pesce is now among the store’s top-five sellers. They’ve had to restock a new coffee-table book, the lavishly photographed Out in the World With Gaetano Pesce, three times.

“There’s no question his influence is widespread,” says Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn of Salon 94, pointing within her gallery’s own roster to designers like Thomas Barger and Jay Sae Jung Oh. When Stout co-taught a class at RISD a few years ago, everything in the furniture department was wildly experimental and very much in the Pesce mode. “Half of it didn’t really work, you know?” she says. “And they’re fully embracing it.”

It’s enough to lead one to wonder if a saturation point is nearing. “The pendulum swing is just about to strike ‘basic bitch,’ ” designer Misha Kahn says. “Once one too many people have a goopy thing in their house, then it’s gonna swing back viciously.” There can be, admittedly, practical issues in living with Pesce’s work, too. Kahn himself owns a Pesce dining table in the shape of Denmark whose jelly legs make it nearly impossible to eat on. “The gallerist was like, ‘Did you realize this was like a table about the instability of the European Union?’ ” he says. Still, Kahn freely admits he is one of the beneficiaries of the rage for Pesce chic. Pesce waves off questions about his influence on younger generations but evidently does have a few thoughts on the subject. “I should have a percentage of everything that that kid ever sells,” he once told a collector of both men’s work. (Pesce says he has no memory of saying so.)

Meanwhile, Pesce’s own market is doing just fine. His prices are rising, and new buyers are discovering him in his ongoing global creep. Rohatyn keeps the commissions coming, although, as she admits, Pesce tends to follow his own inclinations rather than his clients’. “We don’t always know what he’s going to make,” she says. “It’s always so experimental with him that it can take a long time for somebody to get exactly what they want.”

Pesce has little time for a work once it leaves the studio in the clutches of a happy buyer. In Brooklyn, a few floors up from the studio in the Navy Yard, is a separate storeroom he rarely visits, filled tightly with pieces awaiting their next home. The client tends to follow the wishes of the work, rather than the other way around. “Nobody ask anything to me because I am considered someone difficult,” he says. “They say, ‘Don’t work with this guy.’ But we don’t need the people asking me for a chair. We do a chair. Then if someone come here and like the chair, they take the chair.” Al Eiber, a Miami Beach physician and longtime collector and friend of Pesce’s, confirms that the commission process more or less works just this way. That said, he has no complaints. “I don’t want to get his head any bigger, but the guy is a genius,” he told me.

I ask Pesce if he considers how people live with his work. “They like very much,” he says, shrugging. “I don’t know. Me, I don’t visit.” Alisa Wronski, his right hand at the studio, says, “Once it’s outside of the door, you don’t think about it.” At his home on East End Avenue, dominated by sweeping views of the East River, Pesce keeps a worktable, some books, and only a very few of his own pieces. “I have what is necessary, nothing more,” he says. He recalls the assessment a friend gave him: “Your house is like the house of someone leaving forever, tomorrow morning.”

Pesce’s friends say he is a private person, not shy about touting his own genius — in a speech at one of his openings, he (speaking not as himself but as his own fictional “representative”) declared himself greater than Leonardo and Michelangelo — but not given to more art-world kibitzing than necessary. At Salone del Mobile, the furniture fair that is the highlight of the design world’s annual circuit, and at the Four Seasons Hotel bar, its high-school cafeteria, “you rarely ever caught a glimpse of him,” Murray Moss says.

That hasn’t always endeared him to the crowd. “I understand that he’s not publicly beloved,” Moss says. “He has a lot of people that don’t care for him at all.” Not that Moss, a close friend of nearly 30 years, is among them. But even with him, Pesce could be reserved. “He never used to let me into the studio,” Moss explains. “If I would go there, he would bring something into the hallway. For years.” The isolation of the pandemic seemed to suit Pesce just fine: He spent the last few months holed up sketching and making models by hand. “I work, and when I have time, what I do? I work,” he says, laughing. “The epidemic that we had was fantastic for me because I worked so well. I was never leaving the house.”

As Pesce enters his ninth decade, his concern is what it has always been: to make the work that defines the time, slippery as it is. He tells me, “You want to be correct with your time. We have to understand that time is our master. Maybe some talk about God; me, I talk about time. Time is so free that he can say the contrary now or what he said yesterday. And it’s fantastic because he’s incoherent.” Incoherence is an article of faith and a cardinal virtue for Pesce, one he trumpets often and has done since his first show at the age of 18: When reality is incoherent, how can the work be anything but? “Some critics like to criticize me about this idea,” he says. “They treat me like an idiot.”

So the studio works busily to keep up with him, and his thinking has not slowed much in his later years. “To have ideas is very simple,” he says. “It’s a question to think. Certain ideas come when I am in the toilet. Same thing when I am in an airplane. Same thing when I am here.” His newest creation is a large Ballet table whose legs are feet en pointe; it’s the centerpiece of his upcoming New York show. A group of resin sculptures of pregnant female torsos will make its way to Italy for his museum show there. An exploded cabinet with a Pescean message scrawled inside — “Diversity is humanity’s treasure. Vulgarity and ignorance are invading this country. The future is receding and a nostalgia for a totalitarian regime is resurfacing, threatening freedom. This mess will not last and civilization will continue to grow” — was created for Louis Vuitton.

“I really think that people don’t understand him,” Moss says. “He has a totally classical background — I mean, he is like Yo-Yo Ma playing jazz. He simply applies his gifts to something else than that which you would expect. He is like a Renaissance painter, and I see those things now in the abstract globby colorful pieces.”

To the Pesce faithful, he hides his erudition and his genius in plain sight. We turn to talk about a blue lamp shaped like an elephant. Like much of his work, it is jolly and a little silly and charming and startlingly literal. “Abstraction is over,” he tells me. “Me, I say, ‘Look, we have to connect with people something they recognize.’ ” On the ceiling above us hangs a lamp in the form of a plate of spaghetti. “It’s good, imagining all the restaurants,” Pesce says, when a studio assistant clambers up a ladder to plug it in and the entrée glows. “Will be nice to have on the wall, the spaghetti.”

He has little patience for the pieties of tasteful design, which, in the glow of his studio, suddenly seem a bit constipated. Forget the furrowed brow and the interpretive heuristics. Take the elephant. “For sure, it represents an elephant,” Pesce says. “What does an elephant mean to you?,” I ask him, ready for a soliloquy on memory or age or wisdom. He looks confused. “An elephant is a good animal,” he says. “Yes or no?” He has never seen an elephant charge at people; a lion, yes, but not an elephant. (Elephants sometimes do attack humans when encroached upon, but never mind.) “So I make a lamp, a tribute to the elephant,” he says. “They are nice, and I am sure that people will like.”