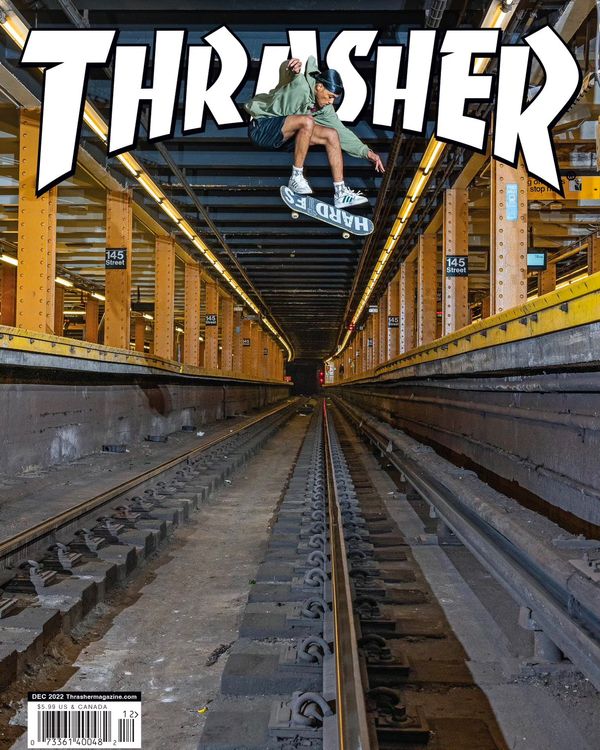

Los Angeles photographer Atiba Jefferson was on a commercial shoot in New York last April when skateboarder Tyshawn Jones asked him if he could get a picture of him jumping over the train tracks at the 145th Street subway station in Manhattan. It wasn’t an unusual request per se. Jones, the best athlete skating has ever seen, has worked with Jefferson, its preeminent photographer, for about a decade now, on some of his most famous tricks. But to properly frame Jones hurling across the gap on his board, Jefferson would have to get down on the tracks.

“It was told to me that the track wasn’t live,” Jefferson said in a phone call from a skate trip in Buenos Aires. “It was.” The first time a D train came roaring into the Sugar Hill stop, he scrambled out with his Canon R5 and cut his hand open. But eventually he learned a better way to dodge the 85,000-pound subway cars rushing his way: standing very carefully on the third-rail guard to boost himself up.

Since Jones went pro at 13, he’s made his career with explosive feats turning New York into his playground: endless hops over Department of Sanitation trash cans, improvising on backhoes turning into Park Avenue traffic, olliing over the 33rd Street Street entrance for the 6 train. The 23-year-old from the Bronx didn’t pick the 145th Street station at random. The platform, two levels below the NYPD Transit Bureau District 3 Station, is about twice as wide as the system’s average. A skater has roughly 30 feet of smooth concrete — maybe a little more if they’re coming in at an angle — to pick up enough speed to jump over the nine-foot gap and the yellow tactile strips. “It’s not a lot,” said Jefferson. On the other side, there’s about half as much real estate to successfully land and slow down or turn to avoid skidding out into the next train gap. The run-up is just long enough for a civilian to think they could make it at a sprint. The gap is wide enough to stop most people from trying.

Coming up short wasn’t really a problem. Jones has an alchemical mix of what skaters refer to as “pop” — the talent, coordination, and all-important vertical to get high enough in the air to make impossible feats look casual. On the first few goes, he cleared the gap but couldn’t quite stay on the board as he came down. Before 5 a.m. and the beginning of the morning rush, Jones flew over the tracks — over Jefferson, over the third rail, and over the spectating rats — and stuck the landing. The smack of the hard polyurethane wheels reverberated in the station. The few friends he had gathered as witnesses roared.

In the shot, recently published as the December cover of the skate magazine Thrasher, Jones is floating in the empty metal corridor. Crouching on the track bed, Jefferson estimated that he was at least nine feet above him. “It’s Michael Jordan from the free-throw line — something that historically hasn’t been done,” Jefferson said.

Or at least not with this much style; the train gap has been cleared before. In 2013, Koki Loaizao ollied over the tracks — the most simple aerial trick in skating, using one’s feet to throw the board into the air. (The MTA called the feat “just plain dumb.”) The video was presented as the first successful jump over the gap, but a year after it went up, someone in the comments of the skate site Quartersnacks posted a video of a guy named Mike from the Bronx jumping the tracks at a similarly proportioned platform at the Fordham Road station in 2012. Mike’s surname has been lost to time.

Last year, Brandon Bonner from Virginia flew in to clear the gap at 145th by placing a sign over the rumble strips for a frontside 180 — basically an ollie where you spin the board half a rotation so the wheels in the back end up in the front. “You have to block it out and think that nothing is going to go wrong, that it’s a normal little street gap or something,” Bonner said. “I was just going for it to charge as fast as I could to make sure I could get it.” As for Jones’s achievement, Bonner said, “that shit looks super-good.”

“You want to bring that speed to the table, and Tyshawn has always been famous for having, like, immaculate pop,” Bonner added. “He’s got some pop out of this world, really.”

“He didn’t do a basic trick like an ollie,” said Jefferson. “He did a kickflip. It’s the difference between a run-and-jump and basically a backflip.” The maneuver involves pressing your back foot down to pop the board in the air while sliding your front foot to the left so it rotates under you to expose the wheel side of the board before catching it with your feet when it turns upright. Now imagine doing all that over a massive gap of certain doom — and at just the right speed to make ensure the name of his company emblazoned on the board makes it into the shot. By clearing the tracks with the hardest trick yet, the king of New York skating has put his name on a classic New York spot.

“He ollied the entrance, he kickflipped the train tracks — it can’t get any more Cinderella story than that,” Jefferson said. “Once I saw he made it, I knew that this was a special photo for me. That’s the only reason I got down on the tracks. Trust me, I tried to shoot it without getting down there.”