Our first visits to our future Harlem house were conducted by flashlight because much of the building had been boarded up. It was impossible to work out what certain parts had once been like. Empty for eight years, it had previously been an SRO, a synagogue and school, and some kind of clinic. Tiny closets held unpleasant bathrooms, stuffed in after the fact. There was graffiti on the walls. The basement held two or three inches of water. The blocked drains had overflowed, ruining the ceilings. It was in many respects disgusting.

But it had been built as a grand family home, and behind the iron-spot Roman brick façade lay a stack of four oval rooms. Four! One would have been exciting enough. The house had kept nearly all its original fireplaces and a great deal of its paneling and plasterwork. It had been built in 1890 by the baking-soda magnate John Dwight, co-founder of Arm & Hammer. His initials were embossed in plaster on the dining-room ceiling.

Not long after we bought the house, members of the Dwight family got in touch to say they had photographs of the building from the 1920s, made when the family had left Harlem. Would we be interested?

Would we be interested! The album, together with the original blueprints, answered nearly all of our questions. Every room, except the bathrooms and the cellar, had been photographed. “It’s the Rosetta stone,” said our contractor, Mike Casey. Our architect Sam White (the great-grandson of Stanford White) said he had never worked with such a well-documented house.

We are not aiming to take it back to the 1890s but to act freely within the general idiom of the original structure. Nearly every room has been restored to its first configuration. The floors, all surviving, were sanded and stained (originally they were carpeted wall-to-wall). The walls are generally painted in rich colors, not beige or taupe. We’ve stripped much of the astonishing carved paneling and made an effort to restore the original architecture of some mutilated rooms.

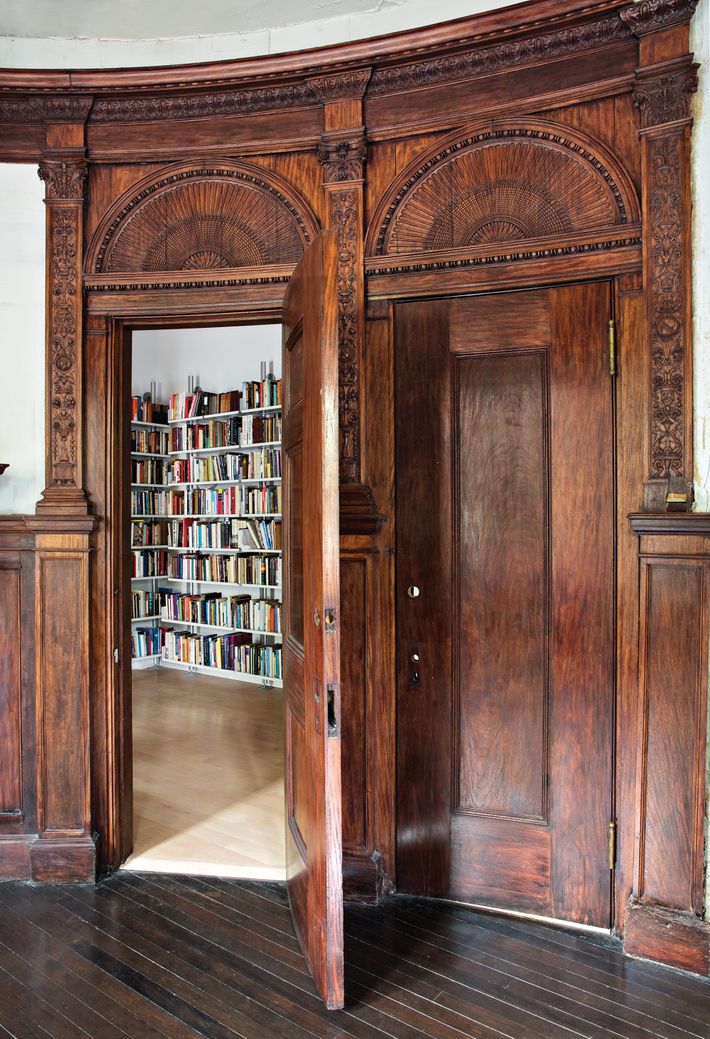

It’s more than we intended to take on. Very much more. But it has its own great satisfactions, chief of which is preservation. We are sure that had we not been the buyers, this battered house would have been gut-renovated, its curved mahogany doors slung in the Dumpster. Instead, they are on their hinges to stay, 125 years after they were hung there.

Renovation architect: Sam White

Built: 1890

Before: A battered beauty that had lived multiple lives.

After: A detailed restoration that’s only partway complete.

*This article appears in the Winter 2016 issue of New York Design Hunting.

The home in the 1920s.

The second-floor parlor in the 1920s.

When the house served as a synagogue, the second-floor parlor was the sanctuary, with a platform and ark set in front of the fireplace. The elaborate plasterwork of the ceiling was intact. The 18th-century mirror came from Florian Papp, on Madison Avenue. The yellow paint is Benjamin Moore’s “Sunshine.”

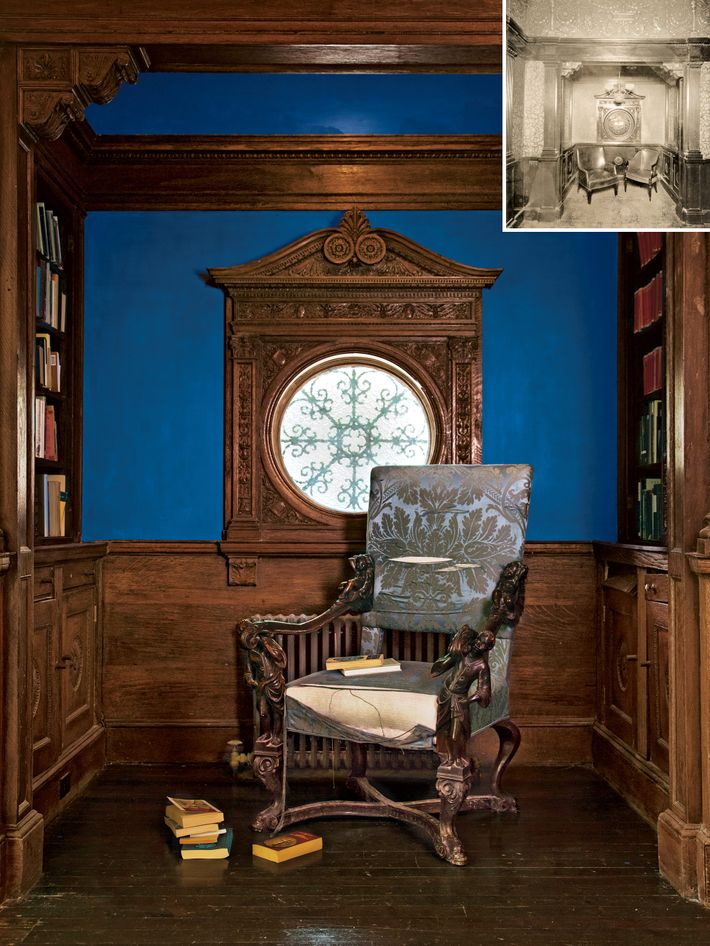

The porthole once held stained glass (top right) and will again; the window is now being restored. The alcove is paneled and framed in deeply carved oak. On the bookshelves, Greek texts go on the left, Latin (in the red-jacketed Loeb Classics editions) on the right.

The oval dining-room ceiling retained some of its plaster ornamentation but lost its elaborate wreathlike border (bottom right). The carved mahogany woodwork had all been painted and needed to be stripped, a painstaking, slow process. The chimneys and hearths are, like the rest of the house, a work-in-progress: Three have been lined and made safe for fires.

The library in the 1920s.

The library on the second floor is in a 1920s extension to the house, with more modern finishes and a new maple floor. The bookshelf system is from Vitsoe, designed by Dieter Rams in 1960. The mahogany doors curve, following the oval shape of the room. The hardware — much of which was gone — was, unlike the woodwork, relatively ordinary and is gradually being replaced.

The kitchen in the 1920s.

The kitchen had been chopped into three rooms. The tiled niche had been behind a wall and was left in its beautifully distressed state. Old photos revealed that the stove had been in the same spot a century ago. The Emeco chairs are made from recycled plastic Coca-Cola bottles strengthened with glass fiber. Both the chairs and the light fixture came from Design Within Reach.