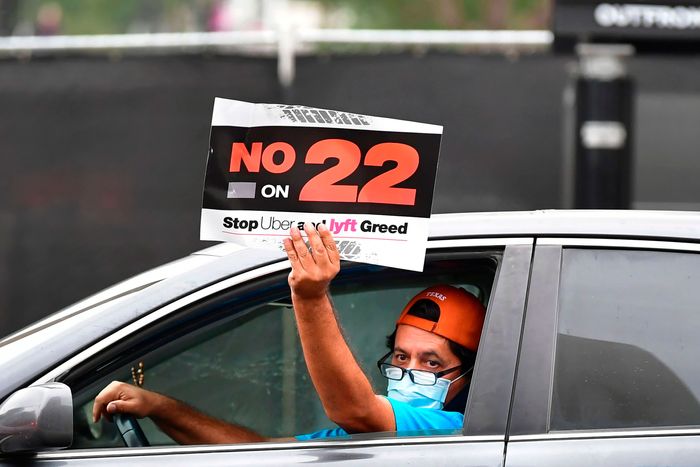

Uber didn’t turn a profit this year. Or last year, or the year before that. But 2020 was good for the rideshare company in one respect. In California, Uber won a crucial public referendum. Proposition 22 allows Uber and companies like it to classify gig workers as independent contractors, and not as employees, who are entitled to certain labor protections. And Uber, like any self-respecting tech company, is already thinking about how to scale up its success. The company’s CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, wants to codify Proposition 22 at the national level. As a new year dawns, Uber looks formidable.

But a scrappy new platform hopes to become a thorn in Uber’s flank. Though the Drivers Cooperative has existed for under a month, its three co-founders tell Curbed that their democratic worker-owned platform has the potential to siphon off drivers from an exploitative rideshare industry. Erik Forman, Alissa Orlando, and Ken Lewis all come from disparate backgrounds; Forman was formerly the education director of the Independent Drivers Guild, Orlando worked for Uber corporate before quitting over the company’s treatment of drivers, and Lewis has driven taxis and black cars in the city for decades. They’re united now in a single conviction: Rideshare companies have taken power away from drivers, and drivers have to reclaim it.

The cooperative model, Forman explained, is “owned by either the workers or the consumers that patronize it or some combination of both.” Applied to the gig economy, the result is a platform owned by the people who use it — in this case, the drivers themselves. Drivers would still be independent contractors, but because they will own the platform, they have more control over their working conditions and will be able to elect the cooperative’s board. Forman and his co-founders said that, without executives or investors around to take cuts of their profits, drivers will be able to keep more of their fares — and riders will pay lower prices.

“It is in fact a democratic organization,” Lewis said, and he believes this egalitarian streak will attract fellow drivers. “Drivers have expressed to us over and over that they feel alienated by the apps. They know they work with thousands of drivers, but they don’t meet them,” he added, and pointed out that this isolation only benefits rideshare companies. An alienated workforce is more difficult to organize and less likely to challenge the image a company presents to consumers. Uber and Lyft did not invent this brutal capitalist logic; it is endemic in the U.S., and has been since industrialization. Nor is it unusual for corporations to present a benevolent face to the public while grinding workers down in private.

The Drivers Cooperative holds up a mirror to the rideshare industry at a crucial moment in its evolution. To win a nationwide version of Proposition 22, Uber needs political support, and not just from anti-union Republicans. Both Uber and Lyft attracted senior-ranking veterans of the Obama administration, and both have representatives on the Biden-Harris transition team. So Uber can’t satisfy itself with selling a service people want; it must also appeal to the liberal conscience. To that end, Uber says that it is anti-racist, queer positive, and pro-worker. As one September ad proclaimed, with Uber, “opportunity is everywhere.” The company has insisted that Proposition 22 will help gig workers. By exempting drivers from AB 5, a previous law which classified them as employees, Uber claimed that Proposition 22 would protect flexible scheduling while granting independent contractors new benefits. If the referendum failed, the company said its workers would suffer, and it would have to raise fares to pay for higher wages. That was a marketing fiction, as organizers and drivers themselves made clear at the time. Weeks after it won Proposition 22, Uber raised fares in California anyway. Drivers, meanwhile, are still working multiple jobs to survive. In theory, a platform like the Drivers Cooperative could offer them an alternative.

Forman, Orlando, and Lewis aren’t the first people to propose a co-op competitor to big rideshare. The general concept has circulated among drivers and organizers for years, both in the U.S. and overseas. But Uber and Lyft have established such dominance over the rideshare industry that any new competitor faces a serious existential challenge. “Lyft cannot catch up to Uber, with all of their venture-capital money,” said Bhairavi Desai of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, a union for yellow-cab, black-car, and rideshare drivers in the city. Taking on major rideshare companies, she added, “would take a tremendous amount of capital. And the only way you balance against that is with a conscientious ridership.” For a co-op to succeed, consumers would have to turn on Uber and Lyft — out of principle or because they found lower fares somewhere else.

Right now, Desai said, that enlightened ridership simply doesn’t exist. “I think that’s a real disadvantage,” she explained. “It doesn’t mean it’s impossible to create enough of a market share where co-op holders can make a decent living. But it does seem impossible to reach the level of market share that Uber and Lyft have at this point.”

Beyond the basic question of their viability, platforms like the Drivers Cooperative provoke another, more philosophical reckoning. Can the rideshare industry even be reformed, or is exploitation simply part of its DNA? But co-op advocates, including Forman, Orlando, and Lewis, point out that exploitation is rampant in the transportation industry at large. Medallion debt has so devastated yellow-cab drivers in New York that several have died in high-profile suicides over the past several years. In a broader sense, to sell your labor for profit in America means exposing yourself to exploitation of some kind, whether you’re employed by Amazon in a warehouse or whether you drive a cab. The rideshare industry exists, and the behemoths controlling it are poised for even greater wealth and power. On Monday, Spectrum News reported that gig companies, including Uber and Lyft, will launch a new coalition with the Arc of Justice and the New York conference of the NAACP to lobby against stricter regulation and oversight in Albany. Circumstances demand creative solutions.

Including, perhaps, an app. It’s easy to slot the Drivers Cooperative into a ready joke: Want to democratize your industry? There’s an app for that. But the co-op model behind the app does call Silicon Valley on a crucial bluff. A mythology powers tech companies and gave rise to the lords of gig work. There’s genius behind Uber and Lyft — genius and the promise of a more efficient and lucrative way to work. But strip that mythology away and what’s left is exploitation. There’s nothing original about the way Silicon Valley treats its workers.

“The legal structure coming from Silicon Valley is not about technology. That is a farce,” said Orlando, who helped lead Uber’s operations in Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya. “The technology of a ride-hailing application is highly, highly commoditized. What powers the Silicon Valley giants is capital.” When the Drivers Cooperative launches its app in early 2021, it won’t have “all the bells and whistles,” she said, because they don’t have billions of capital at their disposal. They’re betting on people instead: on guerrilla marketing, on word of mouth, on the drivers who will define the co-op’s future.

“We’re doing what we can to transform this industry within a market that was created by Uber, by Lyft, and, before them, by taxi base owners,” Forman said. “There are limits to what you can do as one company, but we’re going to do everything possible.”