Last March, my mom mailed me two homemade masks: one that’s a bit too thin to wear on its own and another that’s sewn together from a white handkerchief edged with scalloped lace. Neither of them fits all too well (and the latter looks a lot like a sanitary napkin), so I retired them after a couple of wears. But I’ll always keep them as mementos of the thoughtfulness shown by my family and as symbols of my 2020 life. Someone else may feel a similar attachment to a homemade mask or perhaps to the frying pan they hit during the 7 p.m. cheers for essential workers. For others, perhaps it’s a flyer for a mutual-aid group they participated in or a sign they carried during a protest. For doctors at Mount Sinai, it may even be a ventilator they had to build during a shortage.

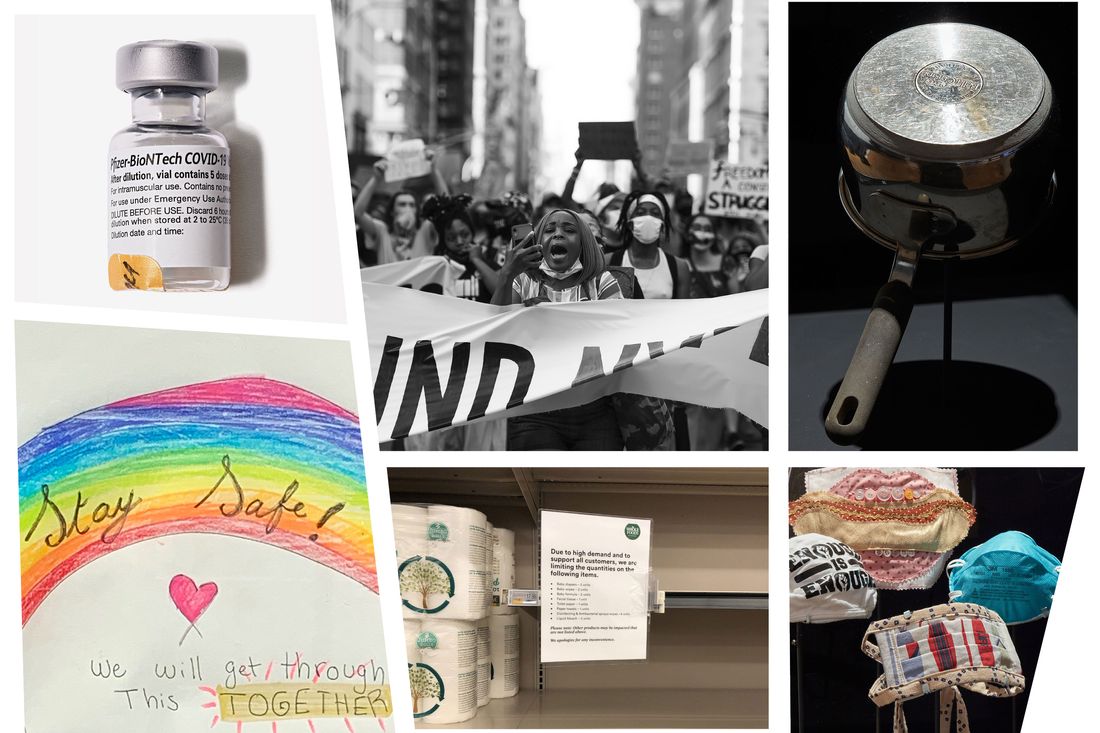

All of these things — homemade masks, pots, protest signs, and that cobbled-together ventilator — are among the dozens of artifacts the Museum of the City of New York has collected over the past year, sifted from the 20,000 submissions sent in response to a public call the museum issued in April for digital media representing the pandemic.

Along with MCNY, other museums and cultural institutions have been racing over the past year to collect and preserve the items, memories, and experiences of the pandemic. Some hasty acquisitions have led to debacles, like the Whitney Museum’s lowball acquisition of photography through a mutual-aid charity sale, which the artists protested because the museum would normally have paid much more for their work; the Whitney canceled the exhibition after public pressure.

We wanted to know what has been filed away in the hard drives and archival storage units of our cultural institutions for the past year. In the following selection of artifacts and mementos, what starts to come into focus is a collection of humble ephemera that feel instantly evocative (things you probably have already thrown away), along with items from the cityscape that were once as novel as the coronavirus itself but have since become normalized (such as social-distancing arrows). Archiving and collecting aren’t neutral acts; cultural institutions now seem to be more aware that they have reflected society’s biases in choosing whose histories and experiences they preserve. Some are intentionally collecting the stories of historically underrepresented groups and social movements, which are important to the narrative of 2020. But few of the items below have been exhibited, so the question still looms: What will we even want to remember of this past year? And what should we? These choices will become the Museum of 2020.

Museum of the City of New York

At MCNY, a jury of curators, essential workers, photographers, artists, activists, and historians sorted through 20,000 submissions from the public to choose artifacts for “New York Responds,” an exhibition about the city’s reactions in the first six months of the pandemic. The show opened on the museum’s terrace over the summer when the building was still under lockdown; it is now on display inside the museum until May 9 and is available for viewing online.

“New York Responds” includes photographs and artifacts that speak to the isolation New Yorkers have felt, the health-care crisis we couldn’t avoid, and the protests that filled the city’s streets. One oral-history video MCNY acquired features a Bronx woman speaking about losing many of her friends to the virus and the disproportionate impact the pandemic has had on low-income Black and Latino people. “It’s like a whole history of people were wiped out,” she says.

To Whitney Donhauser, director of the Museum of the City of New York, the rapid, wide-ranging collection process reflects her view of how museums should better respond to their communities. “In 2020, we’ve learned so many communities have felt marginalized and discriminated against, and so [our responsibility was] making sure that all voices are heard,” she says.

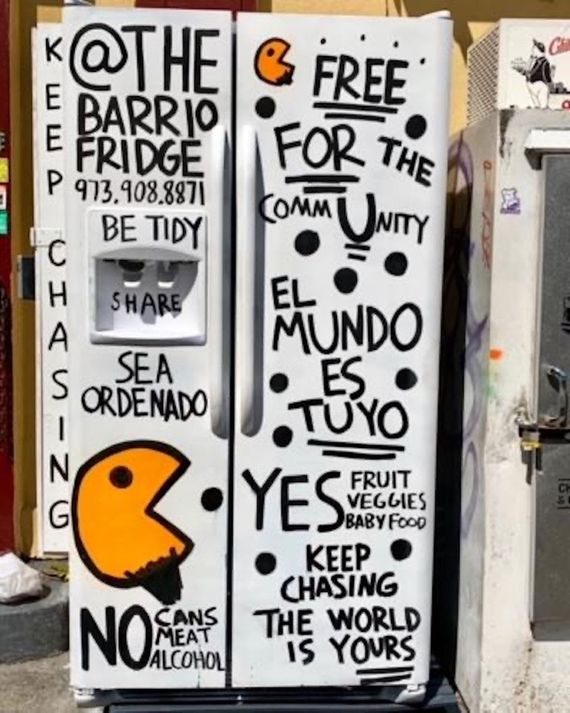

The Center for Brooklyn History

The Center for Brooklyn History (formerly the Brooklyn Historical Society until its merger with the Brooklyn Public Library in October 2020) began collecting for its COVID-19 project last April. Because of the initial uncertainty about how COVID-19 was spread and the attendant stay-at-home orders, asking for physical donations from the public early on wasn’t feasible (it was too risky for donors to mail things, and there was no staff on hand to receive and catalogue them). So the center asked for digital photographs of a long list of items, including the rainbow artworks people taped up in their windows, grocery-store lists and receipts (all those beans!), lesson plans, rent-strike and eviction notices, and mutual-aid flyers.

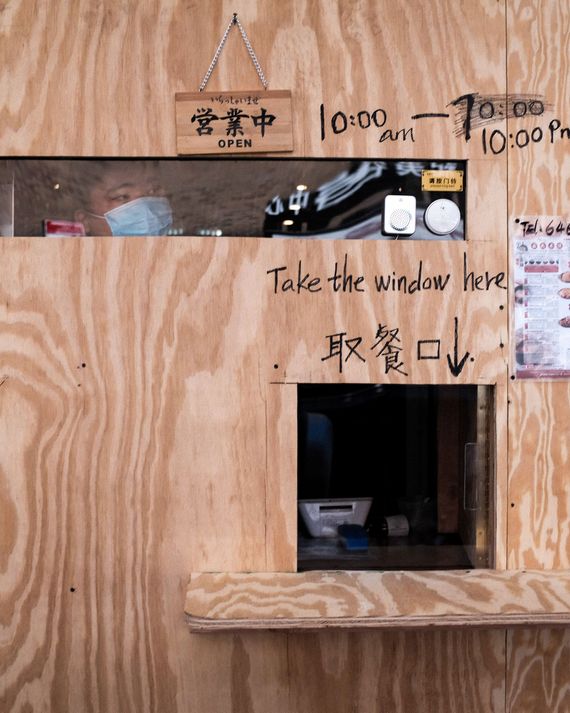

“What we really wanted were things that could fall through the cracks of history,” says Amy Lau, an archivist at the center. “Since people have lost their jobs and are struggling, what we were trying to do through [grocery-store receipts] was figure out what people have prioritized in their life as a necessity.” The digital collection includes images of drugstore signs informing shoppers about shortages, social-distancing markers in parks and businesses, and glimpses of private moments like at-home haircuts. Lau’s personal favorites include a sign on a Midwood halal cart that reads, “Free Meals for Everyone.”

At the onset of the pandemic, the center received an outpouring of photographs taken outdoors and in public, but as time passed, submissions became more introspective and interior. “When you collect for an event, the event usually happens over the course of a week,” Lau says. “And because this pandemic is just ongoing and we don’t know when it’s gonna end, it’s been a very different kind of collecting initiative.”

Lau is now focused on gathering submissions related to the recent wave of anti-Asian attacks that New Yorkers and the country as a whole are experiencing. She has invited one of her friends who has been keeping a diary throughout the pandemic to submit the entries that address these experiences, and she will be keeping an eye out for more artifacts relating to this issue. “This is another area I’m concerned about disappearing too,” says Lau. “That in the future, when people talk about COVID-19, that this gets glossed over.”

Queens Memory

The COVID-19 Project, initiated by the local community archive Queens Memory, was launched after a March New York Times article reported on 13 deaths at Elmhurst Hospital but didn’t say anything about who these people were. That was a turning point for Meral Agish, the community coordinator of Queens Memory. “It was this feeling of, We’re the epicenter of the epicenter, we’re all bewildered, and we’re all freaking out, and we’re looking at this black hole of no knowledge of what the future holds,” Agish says. “Then there’s this realization that Queens Memory is an archive of the people. Let’s see what we can do.”

The curatorial approach of Queens Memory, an archive supported by the Queens Library and Queens College, CUNY, aims to be as comprehensive as possible so any resident of Queens can visit the site and feel as though their experience is represented.

The Queens Memory team, which typically interviews people in person, quickly pivoted to Zoom interviews, posted its online submission form in four languages, and launched an Instagram account to collect as many memories as it could. One woman submitted a video of Mount Hebron Cemetery, near her home, the normally peaceful environs of which were being interrupted by the near-constant sound of heavy machinery digging new graves. Someone else expressed gratitude that their family was safe as a caption to a photograph taken in front of the Lemon Ice King of Corona. These personal artifacts are all available to view via a searchable, geotagged database.

A/P/A Voices

For A/P/A Voices, a digital COVID-19 public-memory project launched in May 2020 by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU, the priority has been to collect Asian American narratives that have been omitted from or misrepresented in the mainstream conversation. “So often, we’ve been seeing depictions of Asian Americans in the media as objects of curiosity or of anger, particularly in this moment,” says Diane Wong, an ethnographer and a professor at Rutgers University who is one of the project’s organizers. “What’s important for us is to be able to provide a space to document the complex, messy, and multifaceted experience of Asian Americans in their own words.”

For Wong, one of the more telling donations to the archive is a Zoom screenshot of tenants in Manhattan’s Chinatown organizing rent strikes. “I think it just really wonderfully captures the different forms of creative resistance that we’re witnessing,” she says.

A/P/A Voices is also collecting oral histories of the social-justice demonstrations that arose during the pandemic. Narrators in the collection speak about marching in protests against the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade. The archive organizers haven’t limited the scope of their collection to what might be stereotypically considered Asian American– or Pacific Islander–related issues but have included pieces linked to other social movements addressing racism, state violence, and housing justice. “Intersectionality and cross-racial solidarity are both really important themes that emerged through the conversations and interviews,” Wong says.

Smithsonian Museum of American History

In March, the Smithsonian Museum of American History announced that it had acquired a coronavirus-vaccine vial and its associated packaging from Northwell Health’s first doses administered in the United States. It also acquired the hospital ID badge, scrubs, and vaccination record of Sandra Lindsay, an ICU nurse at the Long Island Jewish Medical Center in Queens whose vaccination was televised in December.

As one may expect from a history museum with a national scope, the institution’s collecting initiatives related to COVID-19 are broad and include digital photography of everyday experiences, along with artifacts related to the agriculture industry and food shortages, the experiences of refugees, political campaigns, changes in how people worship, and the experiences of communities of color, which include a focus on Puerto Rico. And there are some “celebrity” acquisitions, too: Dr. Anthony Fauci gave the museum his personal 3-D–printed model of the SARS-CoV-2 virion.

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The Cooper Hewitt, a Smithsonian museum focusing on design, is in the process of developing a strategy to acquire artifacts from the past year. The Cooper Hewitt didn’t have a rapid-response strategy (this is a fairly new practice in museum collecting), but in September, it introduced its Rapid Collecting Initiative to try to address some of its shortcomings in this area. After soliciting opinions from museum staff, trustees, volunteers, and curators about which items to acquire, the museum received about 81 nominations — including New York governor Andrew Cuomo’s COVID-19 “New York Tough” poster (of “Boyfriend Cliff” infamy) and the Washington Mystics’ Jacob Blake T-shirt that remembered the Wisconsin man’s shooting by police. The museum is still reviewing them, and as of now, nothing from 2020 has been accessioned into its permanent collection.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

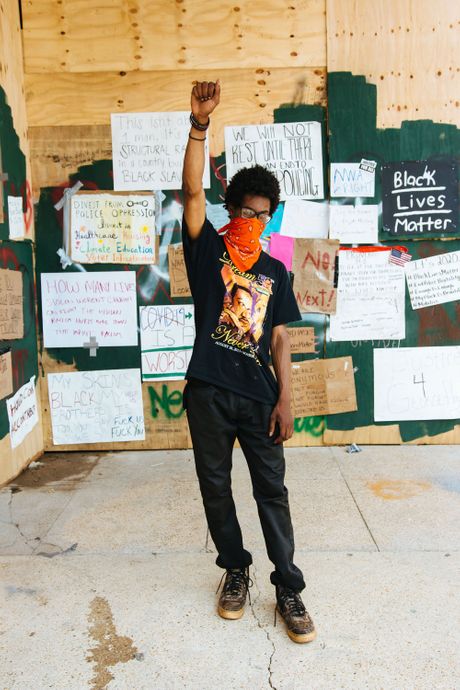

Lafayette Square, a park near the north end of the White House, was the focal point of last summer’s protests against the killing of George Floyd. It was where, in June, Black Lives Matter protesters defied a curfew set by Washington, D.C., mayor Muriel Bowser and where they were tear-gassed and beaten by the police and the National Guard when law enforcement wanted to clear the space for a Trump photo op. Days later, Bowser painted “Black Lives Matter” in 35-foot yellow letters on the street leading to the park and renamed the area Black Lives Matter Plaza as a way to signal allegiance to the movement. (Her record tells another story.) Those letters were then copied on streets across the country, from Oakland to Raleigh.

After the events at Lafayette Square, Dr. Aaron Bryant, a curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and his colleagues surveyed the posters tacked to the security fence for potential acquisitions, and Mayor Bowser’s office donated three Black Lives Matter Plaza street signs to the NMAAHC in the hope that they will be accessioned into the permanent collection. Bryant thinks the signs and posters are important to the events of last June but doesn’t yet know if they will enter the museum’s collection.

At NMAAHC, any artifact under consideration is formally presented to a committee, and the acquisition involves numerous discussions among the staff. But these meetings haven’t taken place since the pandemic began. Bryant is adamant that he and his fellow curators approach collecting with a wide-open viewpoint — “There is no formula because humanity doesn’t have a formula,” he says. Instead, they are working from a philosophy of “emerging qualitative research” and staying open-minded about discovery as our knowledge of this moment in history continues to evolve.

Rather than view last year’s protests and the start of the pandemic as two discrete sets of events, Bryant has folded them into the 400-year history of Black people in America and, more specifically, the Black Lives Matter movement, which NMAAHC has been collecting from since the Ferguson uprisings of 2014. One item that’s part of this collection is a photograph by Sheila Pree Bright from a 2015 Black Lives Matter protest, which includes a person holding a sign calling for trans rights standing next to someone holding a sign with an anti-capitalism quotation from Martin Luther King Jr. that speaks to the struggle for freedom. Another is a photograph by Devin Allen of three young girls joyfully hugging a man during a 2015 Freddie Gray protest in Baltimore.

“Being Black, protesting, and wanting to fight for democracy and equality come in many different forms,” Bryant says. “It would be nice if people were as simple as a ‘No justice, No peace’ sign, but that’s not what we’re trying to do. We’re not trying to simplify the human experience. We’re trying to show how complicated and how complex that experience is.”

Last June, the museum launched “Voices of Resistance and Hope,” a digital storytelling initiative, as a way for people to share personal reflections in the form of short videos, audio recordings, essays, and photographs. The focus on digital items was due in part to health-and-safety concerns, but now that some museum staff are returning to on-site work, NMAAHC is asking for physical artifacts related to the pandemic and the protest movements, including medical equipment, lesson plans for homeschooling and distance learning, works of art, and homemade signs.

The story of 2020 is still unfolding, and events happening now will continue to impact how we understand what occurred in the not-so-distant past. The verdict of the ongoing Derek Chauvin trial and the current unrest in Minnesota over the police killing of another young Black man, Daunte Wright, just miles from that courtroom are sure to affect how historians look back at Floyd’s killing and the Black Lives Matter protests that dominated the past year. New information about the severity of the pandemic continues to be uncovered, such as how Governor Cuomo’s office deliberately misled the public about COVID-related deaths among nursing-home residents. These additions and corrections to history will change the way artifacts are interpreted as well as their meaning. Take the “New York Tough” poster that Cuomo presented in July as a triumph of his leadership; now, it could be interpreted as a hollow, harmful distraction considering it was unveiled while the nursing-home cover-up was ongoing.

And then there’s the reality that we are all still processing the past year. Natalie Milbrodt, the director of Queens Memory, anticipates receiving more submissions about the pandemic for quite a while. “A lot of times, the people who were experiencing the worst of it were not in a place where they could even think about doing something like sharing their story,” she says. “They were still just overwhelmed by living it.”

Correction: An earlier version of the story incorrectly referred to the police shooting of Jacob Blake as fatal; it was not.