It’s easy to convince yourself, after a year in virtual space, that most of the world’s knowledge is either online or can be acquired with a couple of Amazon clicks. Spend five minutes with Julie Golia — curator of history, social sciences, and government information at the New York Public Library — and you’ll realize how wildly wrong that is. “One thing that historians learned this year is that digitization can never replace the archives,” she says. A single collection (out of many at the NYPL) “will have tens of thousands of pieces of material.” Billions of pages are a long way from being scanned. But also, their physicality is information: what was filed next to what, who’s next to whom, which pages are most worn from handling. “That’s information that digitization wipes away.”

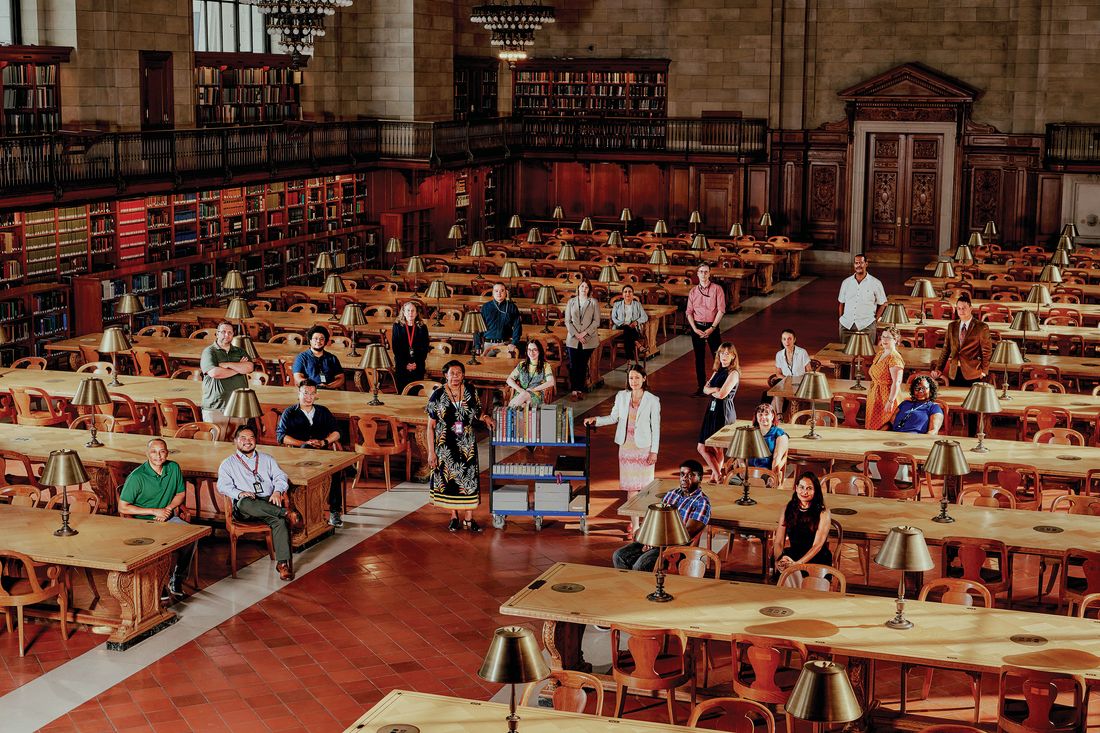

The research library in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, a.k.a. the Main Branch on 42nd Street With the Lions Outside, closed at the start of the pandemic in March 2020. A few months later, about 80 librarians and staff began filtering in “on an A-B schedule,” explains operations manager Fernando Martinez. His team started helping to field digital requests: Patrons could ask for 10 percent of a book or up to 50 pages to be photographed page-by-page. A couple of big book scanners were set up in the landmark Rose Main Reading Room. “It’s really an art to get a good scan,” Martinez says. “The windows are big, so we have aluminum shades on a tripod to direct light, and we dimmed the chandeliers.” In nine months, the staff scanned 151,000 pages for scholars around the world. When researchers were let back in by appointment, the microfilm requests came in a flood. At first, “we didn’t have enough machines.”

Now that the librarians are back en masse (the building fully reopened on July 6), so is their collective knowledge, a lot of which comes from simply spending time there. “Some of our collections use finding aids” — that is, indexes — “that were collected 50, 60 years ago,” explains Golia, “and that description has not been updated. So our librarians are indispensable. When I need an expert opinion on what we have on the history of, let’s say, Black women suffragists, I look in our finding-aid portal, but I also call Cara and Tal and Meredith. They always know more than the catalogue does.”

More From This Series

- Give the Liberty Their Crown

- U.S. Women’s Soccer Fans Are Having a Moment

- Pilgrimage to the Meadowlands (Taylor’s Version)