It was, meteorologically speaking, a perfect forecast. “Significant and life-threatening flooding,” reported the National Weather Service’s New York office on the morning of September 1, as the still-churning remnants of Hurricane Ida headed northeast. “Widespread major flood impacts, especially in urban areas and areas of steep terrain,” it warned. “Areas that don’t normally experience flash flooding, could.” But after the suddenness and severity of the storm and its flooding became clear, a lot of people began to question whether that information had made it into New Yorkers’ decision-making that night. The following morning, as dozens of people had been killed in flooded basement apartments and in cars on roadways, New York Governor Kathy Hochul specifically singled out emergency-alert systems when she asked what had failed. “Is our communication system adequate to let people know in homes and on subways that this is dangerous?” she asked. “Are alerts going out on people’s cell phones? How do we communicate? And are we doing a good enough job? Because I’m not going to stand here and guarantee it won’t happen again tomorrow.”

Conveying the deadly risk of fast-rising waters is the biggest challenge with flash flooding, says Matt Lanza, a meteorologist and managing editor for Space City Weather in Houston, where in 2017 he had to convey the risks of an unfathomable flooding forecast during Hurricane Harvey that ended up becoming the most extreme rain event in U.S. history. “If you go too far, people will tune you out. But if you are up front right away, they’ll listen.” Even though New Yorkers had experienced major flash flooding from Hurricane Henri less than two weeks earlier, Ida’s rainfall prompted the city’s first ever “flash flood emergency.” It’s a newer term, Lanza says, created by the National Weather Service in the past decade to go one step beyond a flash-flood warning and communicate urgency. And it’s likely not a term that New Yorkers were familiar with. “Sometimes you get so hung up on getting the forecast right that you’re conveying all the meteorology, but that’s not what always helps people in their exact situations,” he says. He wonders if language similar to Houston’s warnings about Harvey might have been more helpful, suggesting something along the lines of “Look, we’ve seen flooding a lot around here, but this is the next level, comparable to any of the worst events you can ever remember.”

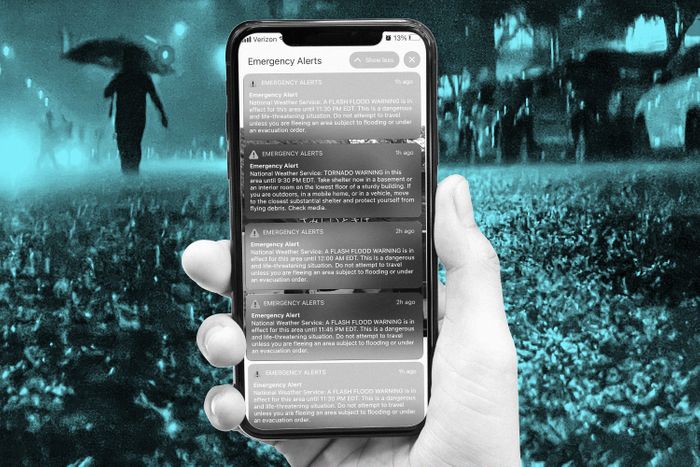

There’s also a question of accurately communicating the danger, since most — not all, but most — New Yorkers are getting this information as push notifications to their phones. On the night of September 1, the National Weather Service sent repeated wireless emergency alerts to all newish phones targeted to a specific geographic area. In addition, people who had signed up for Notify NYC, the city’s emergency alert system — just over 900,000 New Yorkers, getting notices in 13 languages plus American Sign Language — also received alerts, and as the flooding intensified so did the messages; Notify NYC eventually sent 29 of them. The overlapping messages from multiple agencies sometimes confused recipients, illustrating a problem with the way information about this emergency was received: within a single six minute period, some New Yorkers received both a tornado warning alert and a flash flood alert, providing contradicting guidance to simultaneously “take shelter now in a basement” and “do not travel unless you are fleeing an area subject to flooding.”

A warmer future with more overlapping climate catastrophes calls for major shifts in the way information about extreme weather is shared with the public, says Gina M. Eosco, manager of the social science program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “We’re working towards taking our forecast information and translating risk in a way that empowers anyone to take action. That’s extraordinarily difficult to do in these circumstances.” Eosco sees Ida’s impact as a call to action to close the gap between physical science, where our ability to predict the movement and intensity of storms has improved exponentially, and social science, which is lagging. In New York City’s situation in particular, language like “seek higher ground” or “avoid crossing streams” isn’t particularly effective to help a densely populated region assess danger, she says. “Maybe it’s ‘go to a higher floor in your building,’ something with more geographic specificity.” Conveying storm impacts also means communicating the specific risk of rising waters to an urban audience that’s surrounded by impervious surfaces. “It’s not just this complex equation of what is possible in our atmosphere, it’s what will happen when it hits the ground,” she says. For New Yorkers, that includes being attuned to elevation and terrain and the status of nearby drainage infrastructure.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, to his credit, had been working long before Ida hit on trying to get that information to New Yorkers. In May, his office released a stormwater resiliency plan, a series of preventative measures, both physical and policy-related, to be put in place over the next five years, including maps showing which streets are most likely to see impacts from rain-driven flooding events. On Friday, he announced the formation of a task force that would fast-track some of those goals as part of the Climate-Driven Rain Response, a citywide action plan specifically for flash floods that’s meant to go into effect within two weeks. Part of that plan, he said, would be geotargeting emergency alerts to specific neighborhoods with high numbers of basement apartments, followed up by sending first responders door-to-door to evacuate people. Deborah Helaine Morris, urban planning professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and former executive director of resiliency planning at New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, agreed that a mayoral taskforce could hypothetically zero in on specific at-risk neighborhoods using a combination of rental registries, housing data, and the city’s census outreach plan. But she’s extremely skeptical of an approach that relies on emergency alerts and door-knocking to help people who are living in informal housing and understandably distrustful of city government. “Even if you have locally known people knocking, they might not open their doors to them, and when you have a time-sensitive emergency like a flash flood that’s not going to work,” she says. “It’s not a real solution to the problem, which is the danger of being in a basement where stormwater can’t be adequately managed.”

Relying too heavily on geotargeted alerts for certain neighborhoods with low-lying apartments also ignores how rising waters can put anyone in the city at risk, says Brenda Philips, a research professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. What she would like to see the task force focus on is establishing flash-flood shelters in safe locations dispersed around the city, akin to the cooling centers that open in extreme heat. Telling people to stay off roads and out of the subway needs to be paired with directions. “When a travel ban is issued, it signifies the seriousness, but there’s still a question of how you get people to understand the risks,” says Philips. “So you need to communicate risk in terms of other situations, because, in some ways, if you haven’t seen it, you don’t know how bad it’s going to get: This is the rain that will flood the subways. Here’s a shelter that’s not at risk of flooding. Check in on your elderly neighbor.” A travel ban also needs to be accompanied by very clear messaging for workers to stay at home, says Eve Gruntfest, founder of WAS *IS, a community of meteorologists focused on the societal impacts of extreme weather. “It’s not enough to say ‘the subways are closed.’ Employers need to tell people they don’t need to come to work — otherwise people will drive or walk or try in other ways so they don’t lose their jobs.” But more travel bans and pre-emptive closures also means leaders might sometimes overcorrect, says Gruntfest. “There has to be tolerance for close calls where the expected rainfall or weather occurs but not precisely where or exactly when it’s forecasted.” Remember the ire from parents when de Blasio closed schools and then the snow didn’t come?

And that process of learning in public is going to be the real challenge for New York, where these flooding events — and there are more to come — are truly unprecedented, says Lanza. That might mean more customized alerts with better neighborhood maps and data visualizations, but it also means putting more social scientists at the table, helping emergency managers craft messages that won’t numb people with the same robotic jargon over and over. “Of course sometimes you’re going to be wrong,” he says. “But the question is, did local leaders get that message out in time?”