I first became aware of Minoru Yamasaki’s work in the summer of 2001, when I was standing at the foot of the World Trade Center wondering how it could be that I had just graduated with a degree in architecture and I had no idea who had designed the Twin Towers. Fifteen years later, well into my career as a contemporary artist, I started working on this book, uncertain about the practice of making physical objects after seeing so much art work damaged during Hurricane Sandy. I began with the idea of writing generally, but almost immediately arrived at the idea of looking at Yamasaki’s work more closely. It was then that I came to appreciate how extraordinary his story really was. Not only that his two best-known projects — the Pruitt-Igoe Apartments in St. Louis and the World Trade Center in New York — were both destroyed on national television, but also how his unorthodox interpretation of modernism has been relegated to the margins of American architecture history. I wanted to capture his story somehow, but not in a traditional mode of architectural storytelling. I wanted to write about architecture in a way that felt closer to how I experienced it, and the only way to do that was to include myself in the narrative. The following excerpt from Sandfuture includes episodes from my own experience of 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy, spliced together with biographical passages from Yamasaki’s early life and his time working as the lead architect of the World Trade Center.

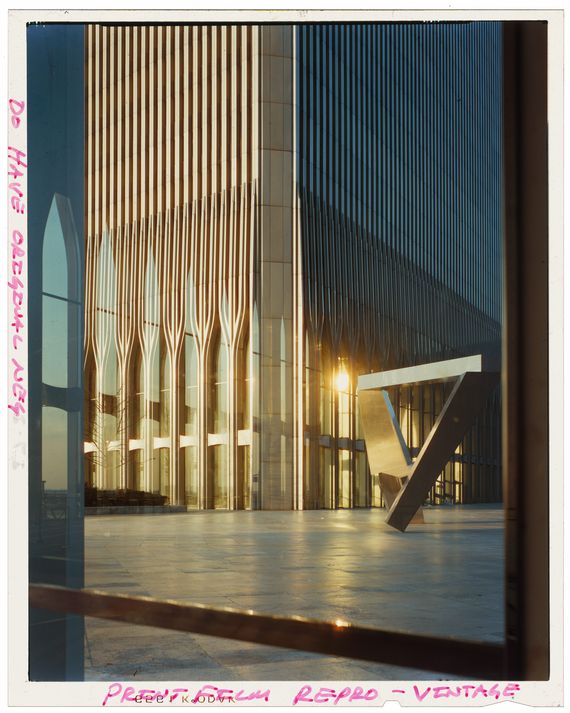

At night, alone in the plaza, you could lean your body against the chamfered corners of the aluminum façade, roll your head back and look straight up the side of the building. It was like lying on your back in the middle of an aluminum road. It was vast and, in that vastness, more closely resembled a naturally occurring phenomenon than something man-made. And there were two of them. You could stand in the space between them, where the air vibrated with silent energy, and believe you were standing between the tines of a tuning fork. Clouds would catch on the upper floors as they passed over the city, subtly altering the weather. They were alpine — a pair of aluminum mountains. They induced vertigo. They exceeded haptic experience. They failed as buildings, but they were brilliant as objects.

When I imagine a work of art being destroyed it is almost always by fire — the spontaneous combustion of linseed oil in rags or nitrate film in storage vaults, Orwell’s memory hole or Savonarola’s bonfire of the vanities. Pinochet burned Gabriel García Márquez. The Nazis burned Thomas Mann. Franz Kafka burned 90 percent of his life’s work and requested that more be burned upon his death (it was not). Vladimir Nabokov and Emily Dickinson left similar instructions. Herman Melville burned his manuscripts and letters. Agnes Martin may or may not have burned all of her paintings when she left New York. Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio, Taliesin, burned to the ground after his cook locked Wright’s mistress, her two children, and several carpenters in a dining room, doused the house with kerosene, lit it on fire, and attacked anyone who escaped with a hatchet — there are still letters in Wright’s archives with singed edges. A prison guard burned the only manuscript of Jean Genet’s Notre-Dame des Fleurs so that Genet had to write it again from memory. Malcolm Lowry saved Under the Volcano from his burning cabin but lost In Ballast to the White Sea. Guy Montag burned libraries in Fahrenheit 451, and Don Quixote’s priest and barber burned the romances that turned the hidalgo mad. Nearly 300 sculptures and drawings by Auguste Rodin were lost in the smoldering ruins of the World Trade Center.

Water feels like a less formidable foe. It drips and dribbles, sluices and sprinkles. Fire rages. A conflagration tears through material with indiscriminate fury, while an inundation rolls passively through channels of least resistance, moving deliberately, inevitably, but without the promise of the catharsis of physical transformation.

Water climbs up onto the narrow swath of park on the Hudson River’s east embankment, washing across the four southbound lanes of the West Side Highway, around the landscaped medians and over the northbound lanes before pooling among the trashcans and hydrants on the corner of 27th Street. From there, the tide flows east in the grooves between cobblestones, carried first by capillary action, then forced from behind by the surge. The surface of the road disappears as the water gradually rises to the level of the concrete curb. It is late in the evening of October 29, 2012. Some water is diverted into manholes and storm drains, but not fast enough to keep pace with the rising tide as the surge pushes massive amounts of seawater up into the South Bay. The current between curbs becomes steadily stronger. The street turns into a wide, flat stream. Gradually, the water breaches the curbs and flows onto the sidewalk. Water backs up against thresholds and weather-stripping and sandbags, finding its way through gaps, into buildings where it crosses polished concrete floors, seeps between floorboards, pools in electrical outlets, and bloats the papered edge of sheetrock walls. Once inside the building, the water seeks its own level, finding new spaces to fill, descending staircases and cascading through trapdoors into the cellars below. The basement spaces are not watertight. Circulation vents, air returns, and unsealed ceiling plenums allow air — and now water — to flow freely between underground rooms. In HVAC parlance, these spaces are “in communication” — as water fills one section of the basement, it fills them all. Every door to the street is the source of a small tributary that runs into a cavernous cellar — an underground swimming pool the size of a city block.

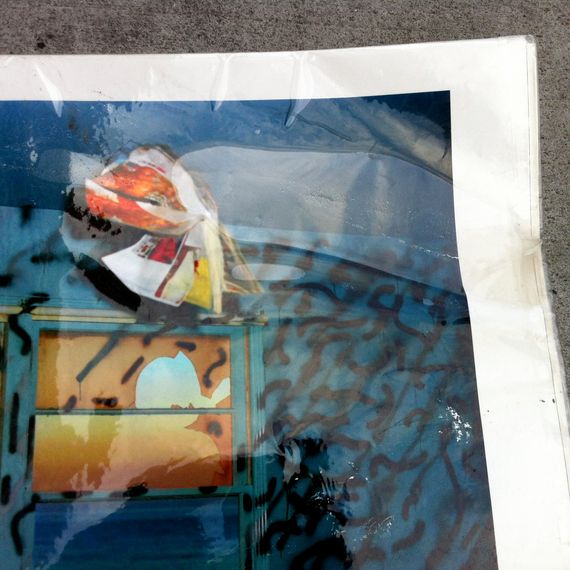

Approximately 2,000 square feet of this basement was under lease, along with the corresponding ground-floor space directly above, to a small art gallery owned by Nina and her business partner Danielle. Accessed through a large trapdoor in the floor of the gallery’s viewing room, their underground space held all the back-of-house fittings typical of the trade — pegboards with spirit levels, spackling knives, tape measures, rolls of low-adhesive masking tape, hex keys, white cotton gloves, and utility knives hanging in neatly organized rows, gray steel shelves stacked with digital projectors and media players with international adapters, large rolls of acid-free glassine, customs forms, ammonia-free Plexiglas cleaner, a tube of mascara, a box of tampons, a lint roller, aluminum Z-clips, brass D-rings, foam blocks, an expired Oyster card, boxes of dead-stock artist publications, and stickers printed with “empty” or “fragile” or “do not open with knife” in thick bold capitals. There were prints stored in steel flat files and paintings in stacked plywood crates with stenciled graphics or filed neatly in carpeted storage racks, each with labels explaining details of provenance. The insurance company had suggested that all work be lifted no less than 18 inches above the basement floor in anticipation of a possible unprecedented weather event. In an abundance of caution, Nina and Danielle had doubled the figure and secured all the work at least three feet above the floor.

As the night wore on, the water level in the basement quickly passed 18 inches, then 36, then 72. It lifted the solid wood stair to the basement upward, uncoupling it from its hardware and setting it adrift. When water rushed between the drawers of the flat file, air pockets trapped at the back of the metal cabinet forced the massive file off the ground completely, causing drawers to slide open and release their contents into the encroaching tide. Later, when the surge receded, these cabinets would look as though they had been dropped from two stories — drawers buckled under their own weight in a heap more than 20 feet southwest of where they had begun. When the water flowing through the trapdoor into the basement had nowhere else to go, it backed up on the first floor, submerging the bottoms of office chairs, filing cabinets, bookshelves, and power strips. By this point, it was a brackish mixture of salt, sewage, dirt, motor oil, and trash rinsed from the street and the cavernous basement spaces no one had seen, much less cleaned, in decades. The tide continued to rise, pushing a grimy high-water mark on the storefronts to 16 inches above street level. It would reach as high as 50 inches elsewhere in the neighborhood.

In the weeks following the storm, the block was lined with apple-green ServePro trucks — a traveling carnival of license plates that diagrammed the movement of the peripatetic disaster remediation industry — tornados in Oklahoma, wildfires in California, hurricanes in Florida. This is a growth sector, expanding incrementally as warming temperatures increase the frequency of force majeure. The army of private contractors and mercenary janitors in khaki pants and wraparound sunglasses, veterans of Iraq or Katrina or Halliburton, arrived in a caravan and unloaded pumps, vacuums, generators, and air circulators from the backs of vans and trailers and spoke only to the landlord. By the time they had set up, the building looked like a body on life-support, with hoses and wires winding from every door and window out onto the cobblestones.

I spent most of that month underground in a full-body Tyvek suit, tall black rubber boots, a respirator with two hot-pink particulate filter cartridges, a battery-powered headlamp, and elbow-length rubber gloves. The basement vibrated with the buzz of halogen work lights and air filters tethered to gasoline generators on the sidewalk. Each piece of art had been placed in the basement with care, with gloved hands, gentle movements, and attention to surface and structure. Such formalities were no longer necessary. Now, each object could be moved as you would lift a bag of topsoil or an old door, with a grunt or a shove. I pulled 12-foot bands of pastel silicone rubber up out of the basement, each as thick as a brick and cracking on the corners from the cold. There were spindly rebar armatures of oversize haunches and torsos, already touched by rust after the cardboard mâché, which had once given them a papery fleshy mass, was carried away with the receding water. I knew all of this work — each object containing untold hours of labor by people with whom I had also spent untold hours long before I met Nina. Among these artists were colleagues and classmates, the photographer who gave me my first teaching job and the friends who had introduced me to Nina. I knew where most of this work was made, where it was printed or cast, the people who processed the film or worked in the foundry. I had seen many of these pieces in studios in various states of completion or in the galleries or museums through which they had passed on their way here. Now, the act of hoisting each waterlogged piece over my shoulder and carrying it up a ladder and out onto the street gave it a new mass. Feeling the physical weight of each object, the deadweight, on my own body, I could not help but think about what an absurd way of communicating this was—making big cumbersome fragile things and sending them out into the world to be looked at.

Minoru Yamasaki, known to nearly everyone who knew him as Yama, was born on December 1, 1912, in a cold-water tenement overlooking Puget Sound. Minoru’s father, Tsunejiro (but known to everyone as John), an immigrant from Toyama, Japan, worked as a stockroom manager at a shoe store, and his mother, Hana, was a piano teacher. In 1926, when Minoru was a sophomore in high school, his maternal uncle, an architect named Koken Ito, made a visit to Seattle. Koken returned to Japan to practice, but his visit left an enduring impression on his nephew. Minoru entered architecture school at the University of Washington just weeks before the 1929 stock market crash. To pay his tuition, he spent summers working in salmon canneries in Alaska.

Nearly a third of Yamasaki’s autobiographical introduction to A Life in Architecture (1979) — until recently the only comprehensive English-language book on his work — is devoted to these summers. These were the stories he chose to tell about himself. The labor in the canneries was grueling, and the living conditions were squalid, with workers contracting gonorrhea from local prostitutes and beriberi from a lack of proper nutrition (Yamasaki blamed this malnutrition for many of the health problems that would plague him later in his life). Men routinely lost hands and fingers on ten-hour shifts shoving fish into a butchering machine known among the managers as the Iron Chink. One summer, Yamasaki got his drawing hand caught in a canning machine, and it took the men two hours to extract his fingers. The workers, primarily of Japanese and Filipino descent, slept a hundred to a room on straw mattresses soaked in kerosene to keep the bedbugs at bay. The pay was $50 a month for three months of around-the-clock work, six days a week. At the end of each summer, Yamasaki would sail back to Seattle in the unventilated hold of a ship where he slept on a hammock hung among racks of salted herring.

In writings and interviews, Yamasaki often referred to these summers as instilling in him the strong work ethic and appreciation of physical labor that form the foundation of his own personal mythology. In A Life in Architecture, he wrote that “when I looked at the older men around me in the canneries, destined to live out their lives in such uncompromising and personally degrading circumstances, I became all the more determined not to let that be the pattern into which my life would fall.”

In architecture school, his colleagues called him Sockeye. He was a strong student, but the intellectual environment was isolated and the Beaux-Arts curriculum was quickly becoming outmoded as modernism took hold in Europe. “No one there, not even the teachers, knew what was going on in the architectural world,” Yamasaki recalled. “We didn’t even know about the Barcelona Pavilion.” Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s pavilion was just one of the seminal projects completed while Yamasaki was finishing his degree — a list that also includes Richard Neutra’s Lovell Health House, Eileen Gray’s E-1027, Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House, and Alvar and Aino Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium.

Neither the Port Authority nor Yamasaki began with the intention of designing the tallest building in the world. The World Trade Center program called for 10 million square feet of office space — more than existed in the entire city of Detroit at the time — and Yamasaki had to figure out where to put it. After working through over a hundred massing models of variations ranging from a complex of six or eight towers to a single monolithic block, he arrived at a scheme of two 90-floor towers in a staggered configuration, reminiscent of (though in crucial ways not identical to) Mies’s Lake Shore Drive Apartments in Chicago. It was an elegant solution, but it only held 80 percent of the program.

Exactly what happened next is unclear. There are almost no remaining records of the design development stage of the project, no correspondence or meeting minutes, no drawings or memos, because the entire Port Authority archive, which at one point included over 75,000 volumes of blueprints and details of buildings and bridges and tunnels across the region, was incinerated in a subbasement storage cage when the World Trade Center collapsed in 2001. It was, in aggregate, a staggering loss of information that included records not only of the World Trade Center but also every other project in the vast Port Authority portfolio.

There seems to be some agreement that Lee Jaffe, the Port Authority’s director of public affairs, had actually been the first to raise the possibility of the tallest building in the world in a memo several years earlier, though at the time, her suggestion was largely ignored. By his own account, it was Tozzoli who flew to Detroit and told Yamasaki, “President Kennedy is going to put a man on the moon, and I want you to build me the tallest buildings in the world.” Either way, what is clear is that at some point during a regular Friday afternoon meeting at Yamasaki’s office in Michigan, the project shifted in a fundamental way — the program that had begun as a large complex of bureaucratic office towers now called for the two tallest buildings in the world. The brief had changed, and Yamasaki could go along with it or walk away. According to one former employee, Yamasaki was visibly shaken by the turn of events, but by the time he returned to work on Monday morning, he had made a decision. He gathered the office together and announced that they were going to design two buildings taller than had ever been built before. In the following weeks, Yamasaki pushed the two-tower scheme from 90 floors to an unprecedented 110 floors — two high-rises with a combined square footage greater than the Pentagon and a footprint slightly larger than an acre each. Yamasaki’s model makers had to remove the ceiling panels in his office to stand the final scale model upright. Tobin and Tozzoli were thrilled.

Shortly after Yamasaki won the commission, Ada Louise Huxtable, writing in Art in America, quoted an excerpt from a lecture he had given on the Voice of America the previous year. Huxtable often seemed to comprehend the narrative of Yamasaki’s work in a way he never could, and the excerpt was a public reminder of how difficult it was going to be for Yamasaki to frame this audaciously large commission in a way that would sound consistent with his own philosophy of design. In the broadcast, he warned his audience that only the abhorrent “dogmas of totalitarianism demand buildings be powerful and brutal — to impress the masses with the absolute power of the state,” and that an overpowering “monument to the ego of a particular owner or architect is contradictory to the principle that each man who uses the building should be able, through his environment, to have the sense of dignity and individual strength.”

Yamasaki had proposed a World Trade Center that would become “a living representation of man’s belief in humanity and his need for individual dignity.” In a personal letter to Tobin, he described the importance of building at a scale that would be “inviting, friendly, and humane.” Adjusting to the new demands of the Port Authority would require Yamasaki to reconcile this vision with the new mandate to build taller than anyone ever had before.

By using two extremely tall towers, Yamasaki felt he could open the space surrounding the building to create an open urban plaza — it was the logic of the tower in the park stretched to an unprecedented scale. Despite the staggering height of the two towers, Yamasaki imagined the plaza, like the open areas of the Piazza San Marco and Rockefeller Center, as a “great open space with sufficient containment and variety to permit its users to observe and relate the overall scale of the towers to the detail of their parts, making them comprehensible and accessible, not overwhelming and forbidding.” It would be, in Yamasaki’s words, “a Mecca, a great relief from the experience of the narrow streets and sidewalks of the surrounding Wall Street area.” He imagined a plaza encircled by arcades and broad water features, with pedestrian bridges and dense stands of trees, but by the time it was built, all that remained was five acres of empty windswept space and three monumental sculptures — Masayuki Nagare’s black granite Cloud Fortress, James Rosati’s stainless steel Ideogram, and Fritz Koenig’s bronze Caryatid Ball (commonly known as The Sphere), rising from a central fountain.

I was at home in Los Angeles when a representative of the as-yet-unbuilt National September 11 Museum & Memorial contacted my gallery about using one of the photographs I had taken on the morning of September 11, 2001. I wondered where they had seen the images. I had only allowed them to be printed once, in a compilation of psychoanalytic essays about terrorism and war for which I had written an introduction and which, until that morning, I assumed only a handful of people had actually read. The persistence of whoever traced the photographs back to the gallery was admirable, but I still felt nervous about putting the images back into circulation. In the end, I agreed because the honorarium would cover the cost of having the negatives scanned — a task I had put off for nearly a decade. The film had originally been developed at a Rite Aid because it was the only place open, and I had been meaning to transfer the negatives to a more archival platform ever since (it was only a matter of time before the cheap drugstore processing chemicals deteriorated). I had avoided these photographs for the same reason that I avoided most discussions of what Joseph O’Neill refers to in his novel Netherland as “the events synonymous with September 11, 2001” — I was unsure how to reconcile the public fact of what had happened that morning with the role it played in my own personal narrative. By avoiding the subject, I could avoid the absurdity of laying claim to the single most significant global event of the new century as something that also felt so intimate and so intensely my own. I did not get hurt and my ties to those who did were tenuous and remote enough that I felt a certain guilt about acknowledging the undeniable way in which my seemingly chance proximity to the towers that morning — at moments only an arm’s length from the aluminum façade — fundamentally altered the trajectory of everything that followed. The kid working at the Rite Aid told me I should sell the photographs to the New York Post as he handed them across the counter. I had not even seen them yet, but soon everyone I showed them to told me I should sell them to the New York Post. I decided I would only give the museum one photo. The honorarium for one would be more than enough to scan everything, so I signed the release and immediately regretted the decision.

I took exactly 73 photographs that morning, and only the first 2 were particularly remarkable. I had a 35-mm. camera in my bag. I did not own a digital camera yet, and it would be another year or so before most cell phones, including my Nokia, would feature a built-in camera. I took the first photograph, the one that is now in the museum, as I stood on the stoop of my apartment building on Greenwich Street. It is a picture of a crumpled piece of paper burning on the street next to an unfolded cardboard compact disc case, some broken bits of acoustical ceiling panel, a piece of string, a few paper napkins, and a passport. I took the second photograph six minutes later and two blocks further north. From that vantage point, about a hundred feet south of the plaza, the view of the North Tower was completely obstructed by the South Tower, so that all I could see was a plume of smoke rising between the buildings. As I used the camera lens to zoom in on the southeast corner of the South Tower, the second plane hit the south façade just outside the camera’s field of vision. I never saw the plane. The photograph shows the upper midsection of the building in sharp three-point perspective against a clear cobalt sky. The south façade, receding more acutely to the left, is in shadow, while the early morning sun lights the east façade. Three massive explosions project perpendicularly from the south, north, and east façades of the tower — three distinct vectors of cadmium-orange fire, gray smoke, and pulverized debris that look more like cinematic pyrotechnics than anything real.

I have no recollection of the impact making any sound, but I distinctly remember a wave of heat passing over my face followed by a compression in my stomach. I knelt behind a white van and put a new roll of film in the camera. The sky was full of sheets of white office paper suspended in the air like plastic flakes inside a snow globe. The event as we now know it was not yet a complete thought. I got a cup of coffee and started walking uptown. My shoes cut the back of my heel, so I took them off and walked barefoot on the cobblestones along Mercer Street. I turned my phone off and on again — on the screen, a pixelated hourglass spun in search of a signal. I was just below Houston Street when the North Tower collapsed on itself. I withdrew as much cash as the ATM would allow, bought a bottle of water, and continued walking north.

Excerpted from Sandfuture by Justin Beal. Copyright © 2021 by Justin Beal. With permission of the publisher, The MIT Press. All rights reserved. This selection may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.