Even as this stop-and-start year progressed — vaccines and reopenings and a return to something that felt kind of like normal life, followed by variants, supply-chain issues, and a wave of cancellations — real-estate plans churned along. Developers and builders continued to push skyline-, neighborhood-, and city-changing projects forward. A few of the buildings listed below are in the thick of construction, others are opening their doors, and all are, in some fashion, debuting in 2022. The success of at least some now feels like a foregone conclusion — the rich, it seems safe to say, still want to live in New York. But others, like JP Morgan’s supertall office tower rising at 270 Park Avenue, feel much less assured: Will commuters ever flood Midtown on weekday mornings again? Will corporate tenants simply decide to take less space and pay less for it? Will East Side Access, a decades-long dream, be a few years too late for the commuters it was designed to help? Big development projects often feel like an act of fortune-telling — guessing the needs and desires of a city years in the future. But these projects, drawn up in a pre-pandemic world, will emerge in an environment that their developers and designers never saw coming.

9 DeKalb/Brooklyn Tower: At 1,066 feet, this JDS and SHoP Architects collaboration is now Brooklyn’s tallest and an aesthetic rarity among the area’s nondescript glass skyscrapers. (Studio Gang’s 11 Hoyt is lovely, but at 620 feet, it’s petite by comparison.) The building, topped out this fall, has the unusual distinction of containing both rental and condo apartments. (Sales start in 2022.) The project also incorporates the 1908 Dime Savings bank, the landmark next door whose air rights it used to soar and whose domed roof will hold the project’s swimming pool. “Tallest tower” is a fleeting title in New York, especially in an area like Downtown Brooklyn, which is ripe for more skyscraper development, but the tower’s design elements will remain distinctive.

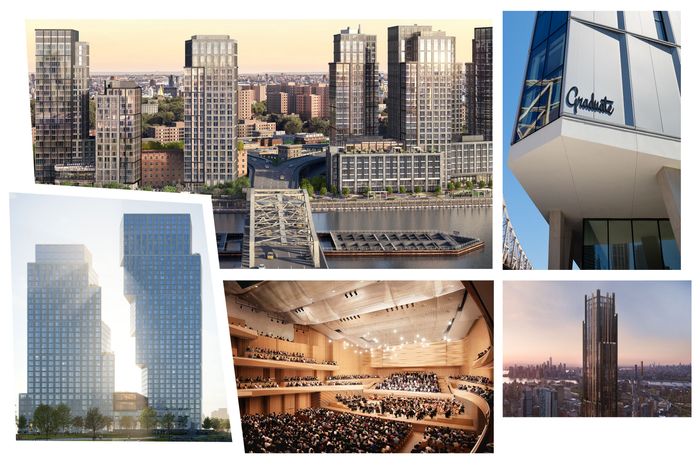

Bankside, Mott Haven: Brookfield’s mixed-use megacomplex in the South Bronx is an unusual development for the borough, which doesn’t see many big new market-rate complexes. Designed by Hill West Architects, New York’s workhorse firm, the nearly billion-dollar project will have seven towers with 1,350 apartments, 30 percent of which will be affordable, as well as retail and community facility space. Though not entirely market-rate, it’s the biggest bet a developer has made on the South Bronx in decades. The project will also open access to Mott Haven’s waterfront for the first time in a century with a public park and esplanade.

Skyline Tower and Sven, LIC: Long Island City’s tallest and second-tallest towers both wrapped up construction during the second half of 2021. Skyline Tower, a condo and the neighborhood’s tallest structure at 778 feet, is the more generic of the two, designed by Hill West Architects and developed by United Construction & Development, FSA Capital and Risland US. Sven, the second-tallest at 762 feet, developed by Durst, was designed by Handel Architects with interiors by Annabelle Seldorf. A rental that’s 30 percent affordable, the building has a curved exterior and is the first New York residential project to feature View Glass, which allows residents to control the tint of their windows through an app. Long Island City’s skyline is one of the city’s most dynamic, even if the predominantly residential nature of the neighborhood’s new development — and the sheer quantity of it — make that easy to forget.

East Side Access: Billions of dollars over budget and decades late, East Side Access, one of the largest transportation infrastructure projects in the U.S., is actually maybe going to be completed this year. The project, first proposed in the 1960s, will extend the Long Island Railroad to a terminal below Grand Central. Once trains start running into the new terminal, some 162,000 people a day will have an easier, faster commute.

David Geffen Hall: It’s basically unheard of for a major construction project to finish two years ahead of schedule. But, in one of the few silver linings of the pandemic, Diamond Schmitt Architects’ $550 million renovation of David Geffen Hall, the Lincoln Center home of the New York Philharmonic, is poised to open this fall, two years early. Because of shutdowns, the project didn’t need to be phased (as had initially been planned). The music will — if everything goes right— sound better, too.

2551 Broadway, Upper West Side: Another looming, utterly unexceptional Extell tower in a sea of looming, utterly unexceptional Extell towers. After building two contentious towers — the 38-story Ariel East and the 32-story Ariel West — on Broadway near 99th Street in the mid-aughts, Gary Barnett has continued to throw up glass tower after glass tower on the Upper West Side. A master of air-rights assemblages, Barnett has arguably done more to reshape the neighborhood than anyone else in recent years, even if the results are undistinguished and the neighbors aren’t very happy about it. He also seems to have cleared away almost all of the remaining lawsuits to proceed with 50 West 66th, which, at 775 feet, would be the Upper West Side’s tallest building yet.

Cornell Tech Campus, Roosevelt Island: The university has finished construction on the Graduate Hotel and the Verizon Tech Executive Education Center, the fourth and fifth buildings to open on the Cornell Tech Campus. The Skidmore, Owings & Merrill master plan won’t be fully embodied until 2043, but these two buildings, designed by Snøhetta, mark the end of its first phase. After opening in 2017, the campus has had a quiet energy befitting sleepy Roosevelt Island, but things will likely become a little more lively with its first hotel and the return of travel.

St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, World Trade Center: The first development at the site that isn’t a mall, memorial, or office towers, the Orthodox church is, after years of financial difficulties and delays that could literally be called “byzantine,” nearly done. St. Nicholas, designed by Santiago Calatrava, has a white marble exterior and is slated to open this spring. Right behind it, in early 2023, will come the Perelman Arts Center, a $500 million venue for dance, theater, and music designed by Joshua Ramus’ firm Rex. (Its translucent white marble panels are already up.)

130 William Street, Financial District: David Adjaye’s first residential tower in New York, although not his first building the the city (he designed an affordable-housing project in Harlem), 130 William is not inherently exceptional — an 800-foot condo tower developed by the Lightstone Group, it has two bedrooms priced in the mid–$3 millions and a $20 million penthouse. But Adjaye’s design, a masonry building that feels fresh while also referencing the fabric of old New York, is. The city needs more alternatives to glass towers and Robert A.M. Stern neoclassicism. If Don Peebles’ Affirmation Tower ends up getting built, Adjaye may soon be working on another project twice 130 William’s height.

Greenpoint Landing: The final two of four residential towers by Brookfield and the Park Tower Group, designed by OMA, will open this spring along the Greenpoint waterfront. They make up 2,000 of the 5,500 units on the 22-acre site, all of which adds up to some affordable housing, more esplanade, and a less old-Greenpoint vibe, low-rise, low-key, and a little scruffy around the edges. Some salvaged maritime pieces found at the site will be incorporated into the open space.

270 Park Avenue: JP Morgan Chase’s new supertall Midtown East headquarters, which involved the largest voluntary destruction of a building ever, is starting to go up. Although opening isn’t expected until 2024, the structure’s rising frame is either a case of chasing after sunk costs or a sign of confidence in the top end of the office market — and thus of the relevance of midtown Manhattan.