In 1971, Faith Ringgold received a grant to create a public work of art. She went around New York, searching for venues that would welcome her vision for an installation dedicated to women. After colleges turned her down — with dismissive “who are you?” comments — Rikers Island welcomed her proposal. “I asked myself, ‘Do you want your work to be somewhere where nobody wants it, or do you want it to be somewhere it is needed?’” Ringgold said in a 1972 interview about the artwork, titled For the Women’s House. The eight-foot-square canvas is divided into eight scenes, showing women as a doctor, a teacher, an athlete, a bus operator, a performer, a bride, and a president — an inspiring vision of women of different ages and races living happily on their own terms. “I wanted to give the women some reason to be proud of themselves and to believe in themselves,” Ringgold said.

In one of her final acts as First Lady of New York, Chirlane McCray announced that the city would move For the Women’s House to the Brooklyn Museum, a plan that was approved by the Public Design Commission last week. It’s a reminder that there is actually a good deal of artwork on Rikers Island, the future of which is uncertain, especially ahead of the jail’s planned 2027 closure. (And given the recent hunger strike protesting the worsening inhumane conditions at Rikers, it strikes me that the city is withdrawing artwork ahead of people.) McCray’s plan represents the first public gesture to preserve the visual history inscribed on Rikers’s walls. But what about the rest of it? Rikers artwork represents a range of perspectives, from pro-prison propaganda to institutional critique, all of which deserves a sensitive preservation strategy. If the city cherry-picks what enters public memory, the work that reveals the most about the effects of the jail may fall through the cracks — if it hasn’t already.

First, what’s actually there?

Rikers is deliberately opaque to outsiders. Photography isn’t allowed, and there are few published images from inside the jail. What imagery does leave the jail is often leaked as evidence of the brutality that detainees endure. But here’s what we know. There are a few main categories of murals: publicly commissioned pieces by famous artists, like Ringgold, and the pieces created by programs like the Works Progress Administration; collaborations between outside organizations and incarcerated artists; installations that officers or Department of Correction programs initiate with incarcerated artists, like hand-painted signage; and then the art that incarcerated people make on their own, often covertly.

The department doesn’t have a catalogue of Rikers artwork, but estimates that there are around 60 murals. “The artwork and murals found throughout the island have become part of our culture and history, and we take pride in showcasing the creative abilities of people in our care,” a DOC spokesperson told me. “We look forward to working with PDC to discuss ways we can best preserve each and every piece of art.” The Public Design Commission doesn’t have a list, either. Keri Butler, the commission’s executive director, relayed that its archive contains documentation only of WPA artworks approved for Rikers and that only publicly commissioned work falls under its jurisdiction. But she added, “While the PDC does not typically review community murals, if DOC wishes to include us in the plan, we are happy to help.”

When famous artists have gotten works into Rikers, it’s usually been through publicly funded programs. In the 1930s and 1940s, the WPA commissioned a handful of murals for Rikers Island, but they’re pretty much gone now — either demolished, like John Xceron’s abstract painting for a chapel, or removed, like Harold Lehman’s Man’s Daily Bread mural, a scene that peddles the myth of redemption through hard work that once hung in a cafeteria. (Lehman only got the commission after the city’s Municipal Art Commission rejected the original commission from the socialist painter Ben Shahn — who proposed a visual timeline of prisons that began with the depiction of their inhumane conditions and ended with Rikers as a model of reform — on the grounds that it depicted “psychological unfitness.”) The only WPA-era mural that is still around is a portion of artist Anton Refregier’s 1941 painting Reconstruction, Home and Family, which shows a frontier family building a home in one scene and gathering for dinner in another. It’s aesthetically (and politically) restrained compared to his other murals. However, famous artists aren’t always successful at bringing their work into the jail. The city’s Arts Commission rejected an abstract mural by Balcomb Greene in the early 1940s. Arshile Gorky designed a stained-glass window for Rikers, but it was never installed.

And sometimes, pieces enter Rikers because an artist makes it a point to bring their work to the jail, like Ringgold did. A Salvador Dalí painting wound up in Rikers after the artist sent it as an apology for falling ill the day he was supposed to lead an art-therapy class in 1965. It hung in one of the jail’s lobbies before it was stolen, and never recovered, in 2003. That painting — a hastily drawn canvas of Christ on a cross with a few splatters and the inscription “for the dining room of the prisoners of Rikers Island” — pales compared to the rest of Dalí’s work.

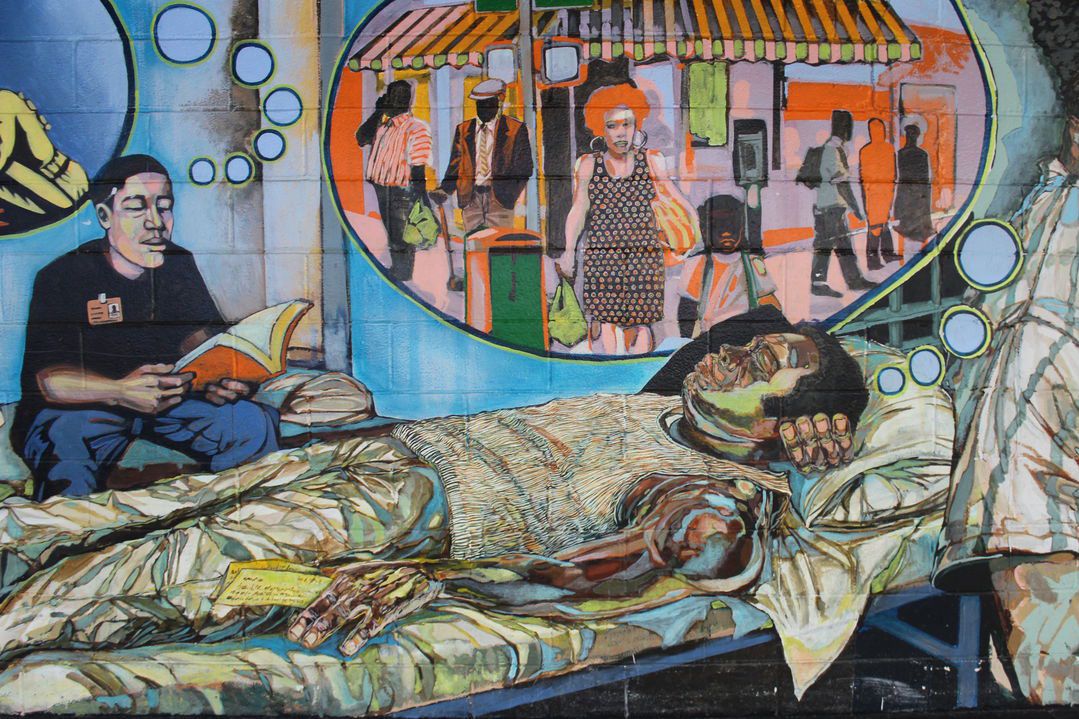

Arts organizations have contributed murals to Rikers as a form of social practice. Among them, Groundswell has initiated at least 40 murals with young people incarcerated at Rikers since 2008. To the organization, the process of making murals, not the end result, is the most important, as an avenue to talk about restorative justice. “These murals aren’t decoration,” says Robyne Walker Murphy, Groundswell’s executive director. “They are about healing, about expression, about sharing voices. We want to acknowledge the circumstances of these young people.” On Rikers, Groundswell partners artists with justice-involved youth to research, conceptualize, and paint large-scale works together. Christopher Cardinale, a Brooklyn-based artist, has painted murals in at least five facilities in Rikers through Groundswell. His first was Incarcerated Minds, which he worked on with the artist Bayunga Kialeuka and 12 teens at Rikers. Painted on a long hallway, it depicts four of those youths daydreaming about their lives outside of the jail with images of their neighborhoods, siblings, and children. “Even though they are young, some of them have children or families of their own,” Cardinale says. “I hope that [our work] with the young people was helpful for them to express themselves and to have relief from the stress they were under.” However, while these murals get much closer at reflecting the experiences of the people on Rikers than the pieces by famous artists, DOC reviews and approves each mural before it’s painted, effectively acting as a censor.

Then there are the murals that are initiated by staff and painted by people held at the jail. As the art historian Parker Field has noted, “The majority of murals created at Rikers are made by artists who are unpaid and incarcerated, which, unlike works made by outside artists, do not circulate widely … and are not recorded.” One of those artists, Anthony Jones, received some public recognition when the Times profiled him in 2001. The reporter detailed dozens of murals Jones made to take people “out of the jail mentally,” which were mostly trompe l’oeil works that turned walls into portals to palace hallways, snowy villages, and landscapes. On his visits to Rikers, Cardinale remembers seeing hand-painted signage and embellishments throughout the complex, like Greek columns and a Looney Tunes character around a doorway and a mailbox painted on the wall of the post office. More disturbingly, he saw stenciled signs on the walls telling detainees where to place their hands during searches and pat-downs. He hopes all of this will be documented before the complex is demolished.

Finally, there are works of art that the people held on Rikers create that are neither officially sanctioned nor publicly commissioned. Art supplies, like paint, are seized as contraband. One art therapist learned that one of her Rikers patients used bars of soap to draw on the walls of her cell while she was held in solitary confinement. No doubt these drawings were scrubbed away as soon as officers saw them.

What actually happens to Rikers art depends on who has the resources and power to preserve or document it. Of all the groups, Groundswell is one of the few that has kept meticulous records of its murals and workshops, and is figuring out how to share them more widely. Robyne Walker Murphy is thinking of initiating a public storytelling project — like a 2017 discussion that Groundwell hosted with the prison abolitionist Angela Davis — and also wants to publish a book about the murals that focuses on “why the piece was done, what were the young people thinking about when they created the work, and a larger examination of the institution itself,” she says. “The constituents that are incarcerated must be centered.”

Art made by incarcerated people, without institutional oversight or that doesn’t pass through DOC reviews, offers the most honest accounting of mass incarceration and its effects on the people and the communities who are directly involved with it. It’s a cruel irony that this work is the most ephemeral and also the least likely to be documented or exhibited. Nicole Fleetwood, author of the book Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, coined the term “carceral aesthetics” to describe artwork that “reflects the conditions of imprisonment.” It includes handmade greeting cards, photographs, drawings, and sculpture made with everyday, ephemeral materials, and is often viewed as having little value by the art world. As Fleetwood writes, “To consider art by incarcerated people as existing outside art discourses or institutions rehearses the violent erasure of being imprisoned.” It’s a hierarchical value system that ought to be flattened.

And then there’s the fact that simply being located on Rikers often leads to art being devalued. The men who were incarcerated didn’t think much of Dalí’s painting (with such a patronizing inscription and lackluster appearance, it’s understandable). In the 1980s, someone chucked a coffee cup at it, damaging the glass covering the canvas. So the warden relocated it from a mess hall, where it hung for 20 years, to a lobby, from where it was eventually stolen. Lehman actually installed his Man’s Daily Bread mural on canvas since its location, a tiled wall, wasn’t ideal for painting directly on the surface. No one knows what happened to it once it was taken down in the 1960s. Refregier’s mural was supposedly moved to an office in 1978 after the warden wanted to replace it with something by incarcerated men. Ringgold’s painting was even whitewashed in the 1990s so the canvas could be repurposed for a DOC-initiated mural. By that time, the women’s house had become a men’s jail, and a guard told Ringgold that men complained that they were “tired of looking at all those bitches.” Eventually, she was able to convince the Department of Correction to restore and reinstall the piece. For a while, it hung behind plexiglass in a gym at the Rose M. Singer Center. Its most recent location was in a hallway.

Around the time Ringgold painted For the Women’s House, she was also protesting racist practices in museums and cultural institutions as a member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition. Her artwork at the time was confrontational, but in For the Women’s House, she preferred to offer an uplifting message to the women at Rikers. “If I hadn’t done it for the Women’s House, then it probably would have been more political,” she said in a ’72 interview. (After an uprising at Attica Prison the previous year, the BECC became heavily involved in cultural exchanges with incarcerated people, and we got a taste of what Ringgold’s more political artwork about incarceration looked like in her poster The United States of Attica.)

In the five decades since Ringgold painted For the Women’s House, she has become one of the most well-known and respected Black artists in America, her work highly coveted. It’s easy to see why a preservation plan for this mural would be created, especially considering the way it was treated in the past and how so much work was lost. “I’m looking forward to the people finally getting a chance to see my painting,” she says about the mural receiving a new steward.

However, she’s not the painting’s only author. Ringgold interviewed women at Rikers extensively to inform the piece. “They said they wanted to see justice, freedom, a groovy mural on peace, a long road leading out of here, the rehabilitation of all prisoners, all races of people holding hands with God in the middle, 85 percent Black and Puerto Rican, but they didn’t want whites excluded,” Ringgold said. She talks of “a kind of universality expressed by their feelings,” but these emotions are mediated by her distance from their experiences. Moving the mural to a museum will further diminish its message since it will no longer be viewed in the context of a jail.

Art offers a way to understand an opaque institution in a manner that words can’t. “If we just go to the public square and people say some words, it doesn’t have the same power as permanent symbols of collective memory,” Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, said in a 2018 interview about art’s unique role in confronting the history of mass incarceration. Rikers may eventually shut down, but the inhumane system that built it will remain. It would be a tremendous loss if only the preachy WPA murals and art-world-approved works were preserved, or if just the DOC-approved images of rehabilitation and reform made it into the history books.

The closure of Rikers is one step toward a reconciliation with the brutality of New York City’s criminal-justice system. But, as Stevenson said, “You have to create a consciousness around the truth before you can have any hopes of reconciliation. And reconciliation may not come, but truth must come. That’s the condition.” That’s why we need all of the art — not just the famous works — to endure in some capacity, because each type of artwork reveals different sides of the institution. The stories of artists who engage in prison-art programs will be different from the narratives that the people who are incarcerated tell themselves. All of it is the evidence of a system at work, as told from the top down, the bottom up, and everywhere in between. And by revealing these truths, they may nudge us to that next step.