For many people, their introduction to the work of Spanish architect Ricardo Bofill comes from the image of his grand social housing project, the monumental and colonnaded Espaces d’Abraxas, standing in as the dystopian headquarters in Brazil and The Hunger Games. For others, the pastel pink walls of La Muralla Roja serve as a frequent Instagram photo-shoot location, or more recently, as a visual reference for the interlocking stairs in Netflix’s Squid Game series. While the dystopian associations with Bofill’s work may be cemented by pop culture, there’s a lot of color and wonder that’s missing from that imagery, which is perhaps unfair to those projects that were intent on making great architecture for all (and, in many cases, were successful at it).

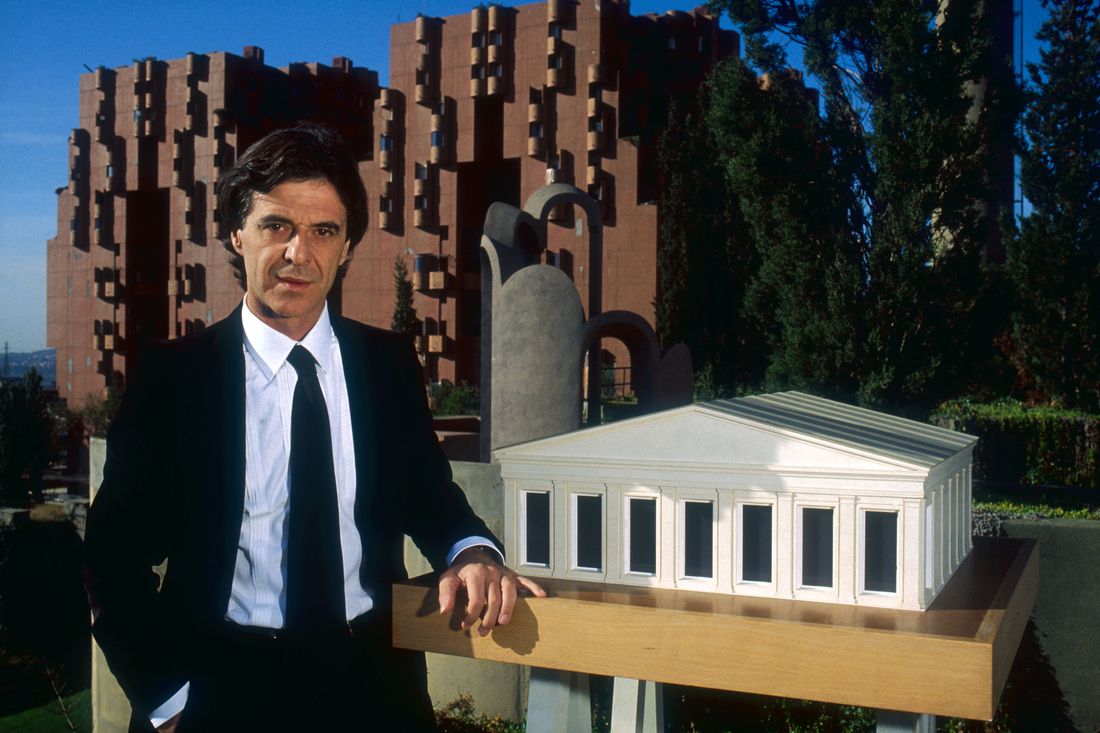

I first learned of Bofill’s work in the same place I learned about most of my favorite architecture — on the floor of the community college library, where my mother dropped me off after school, while paging through a minor (though physically quite large) 1982 coffee-table book by Charles Jencks called Architecture Today. It was one of the first books I bought as an adult, and it still takes up the entirety of my lap. The examples of Bofill’s work inside are more obscure, the first being the cozy yet intricate nesting forms of the 1964 housing project Barrio Gaudí, a massive complex of 600 apartments compiled in a sea of terraced balconies, which somehow draws to mind both Habitat 67 and Miami Vice, both the epitome of cool. Next are the Arcades du Lac, a waterfront housing project outside Versailles. Only Bofill could come up with something as weirdly fanciful as a giant colonnade of apartment towers extending into an artificial lake like some kind of mass-housing aqueduct. Finally, a full-color page is devoted to Le Parc de la Marca Hispanica monument, commissioned to mark the highway border crossing between Spain and France, in which a temple sits atop a pyramid made up of highway rubble, a combination I find both playful and surreal. As I examine the fantastical images, feelings from long ago resurface — feelings of awe, curiosity, disorientation, smallness. However this time, they mingle with sadness, for Ricardo Bofill has died at age 82, a casualty of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite his international fame, Bofill was first and foremost a Catalan architect. The region’s political program of autonomy and defiance against the fascist Franco regime is present throughout the late architect’s legacy and much of his work, which is often filled with homages to the Catalan vernacular — in the use of terra-cotta, intricate terracing, and delectable colors. Hence, he is considered part of the architectural movement known as critical regionalism, which described architecture that was specific rather than universalist — responsive to site, climate, and local material culture. After stints abroad in France and Switzerland, he lived and worked with his multidisciplinary firm, Taller de Arquitectura, in Catalonia for most of his life.

Second to this, Bofill was a socialist, so much so that he got kicked out of the Barcelona School of Architecture (as well as jailed during his brief tenure in the Spanish Army) for flirting with politics, and was exiled to Switzerland, where he completed his studies. This socialist undercurrent drew Bofill toward the mass social housing projects for which he is best known, and his beliefs were considered dangerous enough that one of these projects, the City in Space, was stopped in 1970 by a Francoist mayor. Socialism also instilled in him the utopian desire to imagine new ways of living, freed from the confines of capital, ownership, and the institution of the nuclear family, and this extended beyond the design itself to how his social housing projects were owned and managed. Even today, his most famous housing complex, the jagged, sprawling, modular Walden 7, is still self-managed by its residents and owned collectively rather than by a single entity. (Though Bofill admitted to the critic Oliver Wainwright that the residents had become a bit insular and conservative.)

While Bofill’s work was explicitly ideological, he himself was no rigid ideologue, and his architecture reflected that sense of unrestrained experimentation. He borrowed heavily from psychology, behavioral analysis, and the work of Michel Foucault (all very un-Marxist). He didn’t just design socialist housing projects, but luxury commercial developments such as the sail-like W Hotel in Barcelona and the high-PoMo 70 West Wacker Drive in Chicago. When the times changed, stylistically speaking, he changed with them, integrating the modernist social project (although much of his work is too surreal for the starkness of modernism) with the postmodern aesthetic one (whose forms he made monumental to the point of distortion), most explicitly in Les Espaces d’Abraxas in Noisy-Le-Grand.

Many of his most famous works, despite their vernacular ties, are otherworldly and decidedly unsubtle, a departure from the other architects designated as critical regionalists such as Tadao Ando and Carlo Scarpa. However, like Scarpa in particular, Bofill was also capable of nuance in adapting and reusing existing buildings. Perhaps his most sensitive and most personal work is La Fábrica, the derelict cement factory on the site of Walden 7 that he delicately transformed into his home and the studio of his practice, which will now be inherited by his sons. He did this not with the modernist’s fetish for industry and technology (i.e., Le Corbusier’s love of grain elevators), but with the 19th-century architect’s love of picturesque ruins — he does not attempt to rebuild the factory but accepts its dilapidated condition as the starting point. Of the project, he once said, “I wanted to live there for the pleasure of the challenge.” And looking at pictures, the challenge ended up being quite pleasant indeed.

It is no coincidence that the buildings Bofill is most remembered for are those that were the most explicitly idealistic, the ones he built as late as the 1980s — long after the great housing experiments of the first half of the 20th century had begun to lose steam. Many late modern architects such Paul Rudolph and Kisho Kurakawa had since confined such ideas to paper architecture in the ’70s, but Bofill got them built. Abraxas, despite its depiction in film as the headquarters for totalitarian states, was built as public housing, designed to shelter the poor and often migrant populations who sought refuge and employment in nearby Paris, inhabitants who still live there today despite the building’s fame, and who were key in organizing against its first threatened destruction in 2006. As Bofill told SSense: “I have spoken to many people from France, Africa, China — people from all over the world who live in Abraxas — and they are all immersed in it, they all participate in the theater. The space has a magnetic effect, and people do not want to abandon it.”

He shifted the conception of mass housing away from bleak tower blocks toward colorful, inventive spaces of surprise and discovery. The success of projects like Walden 7 and even the resiliency of Abraxas deserve to be revisited at a time when the idea of building mass housing has been sidelined for decades due to cuts in public spending and the increased privatization of state assets, not to mention the stranglehold of urban planning laws that make such projects less feasible. While some of the great works of the welfare state, such as Erno Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower, have been turned into very, very expensive condos, the people who lived in Bofill’s projects loved them so much they kept them alive through collective management, organizing against decay, and yes, through the joy of many parties. Contemporary critics may look at social housing as one big human experiment — one decidedly impossible or undesirable to replicate — but in Bofill’s case, he proved it could be done and with great fun, too.

Still, even he acknowledged that perhaps the times had changed so drastically that the scale of his monumental projects were no longer possible anymore. As he said in this SSense interview, “Up until the year 2000, the most well-prepared individuals were capable of making future predictions or providing prognoses. Since the year 2000, this capacity broke. And it is in times of uncertainty small gestures — writings, statements, concise and diverse actions — are necessary. Small monuments in a world of flux. These are, in a certain way, the only type of works that can be done today.”

Indeed, Bofill’s influence lives on in piecemeal in our contemporary architecture. His formal complexity and dedication to social housing can be seen in the work of Peter Barber; his drive to rehabilitate “failed” projects is taken up by the French practice, Lacaton and Vassal; his playfulness toward classical form can be read in the projects of Amin Taha’s Groupwork. However, all of these things, wonderful as they are, resist being integrated so perfectly into one firm.

In the wake of his absence, I am left with a certain gnawing feeling that something irreplaceable is gone. The general state of our architectural “heroes” — of those with such a strong social conscience and so explicit a political program — seems bleak. Yesterday’s greats are fading fast; the deconstructivists, like Frank Gehry and Peter Eisenman, are entering their twilight years, and Rem Koolhaas, the last really popular architect-polemicist, is getting on in age. Who is left to inspire us? Not Bjarke Ingels, whose “theory” feels like excellent marketing slogans and not much more — Yes Is More! Hedonistic Sustainability! — or Thomas Heatherwick, whose insipid and often failed follies (remember the Vessel, the beehive-like monument to itself that benefited no one and in the end became a suicide magnet?) continue to foist themselves on cities around the world.

Perhaps the only light at the end of this dim tunnel (ironically within an article mourning a great man) lies in the end of “great men,” and in the democratization of the field from the bottom up, from the academy to the megafirm. It feels oddly historic that Bofill should leave us on the eve of strikes at universities, at the precipice of the unionization drive at SHoP, at the recognition of Peter Barber’s works by RIBA, of Lacaton and Vassal winning the Pritzker Prize (as worthless as it is), of Kshama Sawant beating back Amazon in Seattle and taxing it to build public housing. These are things that speak profoundly to the truth that just because architecture is losing its great ideologues of the past does not mean it isn’t carving out for itself an ideologically charged future. I think it’s one that hopefully, and with great effort, Bofill himself would be proud of.