Last October, a gray wolf with a purple radio collar was spotted wandering in the mountains about 50 miles north of Downtown Los Angeles. OR-93 — named that because he had traveled from a pack near Mount Hood, Oregon — was the first gray wolf to roam into Southern California in a century; the last one observed in the region had been trapped in 1922. But after weeks of excitement from wolf-watchers, OR-93 was found dead by the I-5 freeway. According to the scientists who tracked his movements, OR-93 had crossed dozens of roads and even several highways during his 1,000-mile journey. This made his death all the more devastating: Had he made it to the other side of this final freeway, he would have almost certainly survived, and most likely thrived, says Beth Pratt, California regional executive director for the National Wildlife Federation. Directly across the freeway from where he was killed is the largest contiguous private property in California, a 270,000-acre nature preserve. “It’s our fault,” she says. “We failed him. I wish we had a crossing in place for him.”

Wildlife bridges have long been built over highways to protect roaming animals whose populations are threatened by the vehicle-centric lifestyles of humans. A network of crossings over the Trans-Canada Highway has reduced elk collisions to virtually zero; there’s even an adorable bridge for migrating crabs in Australia. For more than a decade, Pratt has been advocating for one particular piece of infrastructure that she says could protect Southern California’s local mountain lion population from vanishing forever. The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, proposed for the Route 101 freeway on the western side of Los Angeles County, will allow mountain lions to easily cross eight lanes of traffic, substantially expanding their habitat. As of this week, additional funding has been secured for the $87 million crossing, including a final $10 million allocated by Governor Gavin Newsom’s new budget. Now the project is planned to break ground this spring, and when completed sometime in 2023, the nearly one-acre bridge will be the largest of its kind anywhere in the world and the most ambitious in such a densely (human-)populated region.

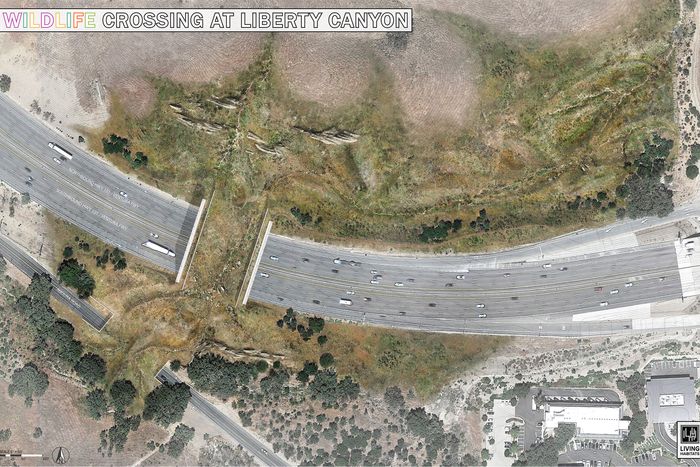

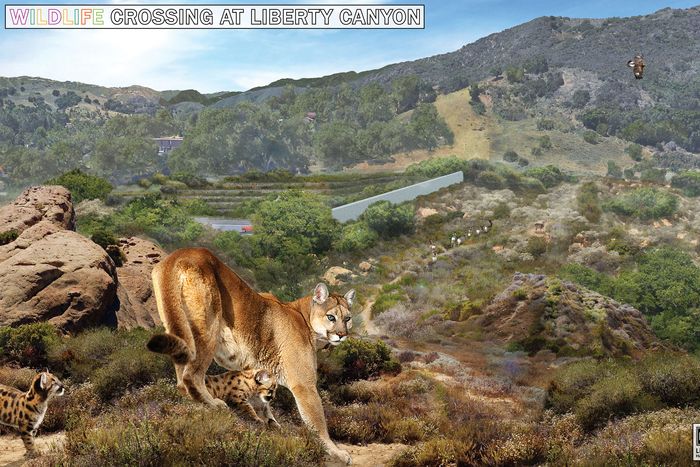

The crossing is planned for Liberty Canyon, where the 157,700-acre Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area extends over the 101 freeway, bridging a barrier that prevents wildlife from moving north to other open spaces. While many wildlife crossings have a more utilitarian design — a bridge in Utah with a viral webcam looks more like a gravel drainage ditch — the Annenberg Wildlife Crossing will be a lush, planted parkway with matte materials to deflect bright headlights and insulation to quiet the roar of cars below. Landscaping with native flora is currently being propagated in a nursery, ensuring that the 200-by-165-foot bridge will attract pollinators like butterflies and bees and that the naturalized path will provide safe passage for mountain lions as well as other animals — like coyotes, bobcats, rabbits, snakes, and toads — hemmed in by development. Restoring the biodiversity that once existed in this canyon, particularly in fire-prone areas, also happens to be an excellent climate-resiliency strategy, says Pratt. “What you’re really talking about with climate is fragmentation, this degradation of an entire ecosystem.”

Mountain lions are a protected species in California, but if the state’s populations are unable to interact with each other, they face a more existential threat than speeding cars or encroaching sprawl. The ability to roam over a wide region — males can have a 150-square-mile territory — helps prevent inbreeding; low genetic diversity can cause physical abnormalities that lead to reproductive issues and eventually extinction. For instance, P-22, arguably the state’s most famous mountain lion, has lived in L.A.’s 4,310-acre Griffith Park, an urban park ringed by freeways, for most of his 12 years; his journey directly inspired the crossing concept. Pratt calls him the “Brad Pitt of cougars” as a way of describing the middle-aged bachelor cat’s dilemma. He may look good, but without the freedom to safely reproduce, he’s not technically healthy. “It’s not that P-22 shouldn’t live in Griffith Park,” she says. “But he would be more likely to succeed if he could get easily in and out.”

Transportation planning largely does not take the habitats of species other than humans into consideration, but L.A.’s proposal could help change that. Wildlife bridges received $340 million in the federal infrastructure bill, and as Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg noted yesterday, preventing such collisions makes roads safer for humans too. According to the Federal Highway Administration, about 300,000 wildlife collisions happen on U.S. roadways each year — “Those are just estimates,” says Pratt, “and that’s just the big stuff” — but many are not reported. Pratt says the solution doesn’t necessarily mean building dedicated infrastructure for every animal; rather, it’s about creating more corridors similar to this one, where humans can move around safely without murdering other living things (or each other). “We don’t necessarily need a Yosemite on every block, but we do need to connect these parcels of open space,” she says. “We need these everywhere.”