No one who works at Lumon Industries knows exactly what the company does. The fictional corporation at the heart of Apple TV+’s Severance is a massive place — and massively opaque. Why are there baby goats running loose? Why are people 3-D printing hatchets and watering cans? (Surely there are more effective ways to make gardening tools!) What the hell do all those coded numbers sent to the Macro Data Refinement office actually mean? As enigmatic as their work is, one thing’s for certain: They’re expected to perform their duties happily, respect the chain of command, and treat procedure like gospel. It’s a posture of corporate professionalism that’s reflected in the architecture of Lumon: an enormous mid-century mirror-glass box with an atrium that looks like a modernist cathedral. The building is dead center in an elliptical suburban office park where the roads leading up to it and the parking that surrounds it are arranged in perfect symmetry.

Lumon is imaginary, but the building is not. It’s in Holmdel, New Jersey, and it was the home of Bell Laboratories, the research operations of AT&T. Designed by Eero Saarinen and opened in 1962, it was a showpiece for the monopolistic, cash-rich corporation that dominated American communications for the telephone’s first century. This iteration of Bell Labs was — in the words of the institution’s biographer, Jon Gertner — an idea factory, the place whose thousands of scientists and engineers discovered or created so much that makes the modern world what it is. The laser, the cell phone, the Big Bang theory: They all came from here. Its researchers won nine Nobel Prizes. It was an extraordinary technology incubator. It wasn’t accidental, of course, because Bell Labs represents the height of an era when offices were designed as a sort of corporate utopia, at least in the eyes of the people who made them. “I always felt a sense of power in these [corporate] spaces,” says Jeremy Hindle, the show’s production designer. “They’re there to dominate you and make sure that you know the rules.” It was the perfect backdrop for a show about a workplace with near-total control over its employees.

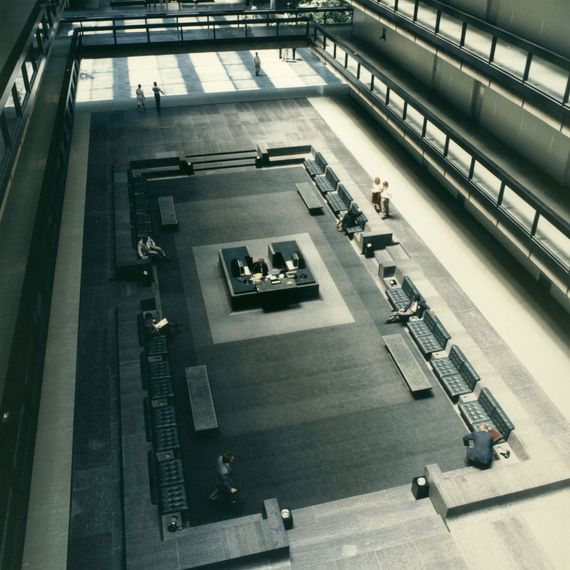

When Hindle talks about Bell Labs, he sounds almost rapturous. “They really did try to create this perfect working, living world,” he says. “People had dance shows, their own farmers’ markets — they had everything in that place. It was amazing. When I look at buildings like that, there’s pride in the corporation and pride in being part of it.” And it is beautiful. When the late-afternoon sun hits the building’s reflective facade, it glows golden. Historians called it an “Industrial Versailles.” Inside, you’re met with a six-story-tall glass atrium that once held 3,600 trees, shrubs, and plants. AT&T leadership wanted its scientists to have “serendipitous” encounters — a buzzword that designers and CEOs still use — with one another, so Saarinen gave them wide hallways and employee lounges and generously sized balcony ledges with built-in ashtrays every few feet overlooking the atrium. “The individual, emerging from concentration in laboratory or office, will come upon magnificent, uninterrupted views of the surrounding countryside and the winter-garden interior courts as he walks, in moments of relaxation, down these periphery main corridors,” Saarinen said.

But Hindle says the mid-century aesthetic wasn’t written into the script. “It read just like an episode of The Office, and was budgeted for a show like The Office,” he explains. The only cues he received ahead of planning the show was that there would be a dance scene and that the ceiling would need to light up. Otherwise, it’s a fundamentally sinister workplace: One of the few established bits of information about Lumon is that “severed employees” have microchips implanted in their brains that separate who they are inside Lumon (the “innie” version of the characters) from their personal lives outside (the “outie”). The innie and the outie are the same person, with the same temperament, but with no memory or recollection of the inverse world, and presumably none of the emotional baggage. As workers with the chip descend in an elevator to the “severed floor,” the chip kicks in and they assume their innie persona. When they leave, the chip turns off and they resume their outie lives, with no memory of work, including their co-workers or the relationships they have with them. (By the end of the first season, we learn that these chips can be overridden by their managers even when they’re not at Lumon, but the full truth of how the chip works is still unknown.)

Because so much of the show involves formal workplace etiquette and protocol, Hindle instantly pictured postwar offices on his first read of the script. During the 50s and 60s, there was a clear division between your work and your personal life — a less extreme version of what’s happening at Lumon. Saarinen’s design for the John Deere Headquarters in Moline, Illinois, finished posthumously by Kevin Roche in 1964, was one of the first references Hindle used as he was beginning to design the show. “Who doesn’t want to work in that space?” he says. “It’s so powerful and prestigious and beautiful. It’s just work, but you feel like you’re doing something awesome.” As he and his team researched other offices from the era, Hindle learned that Bell Labs had been restored, and got permission from the new owners to film there.

The real-life mid-century corporation did not have microchips to influence their employees, but they did have design. In theory, environments that made workers feel happy, energized, calm, productive, relaxed, and collaborative could attract the most talented people, who in turn would do better work. Bell Labs certainly aimed to be that kind of place, starting with its site in the “countryside” an hour’s drive southeast of Newark. “Corporations were convinced that the landscape settings of their campuses attracted the best engineers and scientists and fostered innovation,” writes Louise A. Mozingo in Design for the Corporate World, 1950-1975 about the invention of the suburban office park. At the time, they were competing with universities and governmental labs for employees, so they mimicked the look and feel of a college campus, with monumental buildings surrounded by grass and trees. Prior to Holmdel, Bell Labs scientists worked in an old factory on West Street, in Manhattan, where they griped about all of the city noise and activity — dust, vibrations, and electrical signals — that interfered with their work. (In 1970, that building was converted into Westbeth, the artists’ housing complex.)

In old publicity photographs of Bell Labs, the employees are smiling, happy team members. But while the labs worked pretty well as labs, the “serendipitous encounters” that Saarinen had tried to engineer didn’t really work. Most of the 6,000 people who worked at Bell Labs used the smaller interior aisles instead of the wide hallways to get to and from their offices, and they complained about how isolated they felt. And it turned out that the organization itself didn’t have all that long to live. In 1984, the Bell System was broken up by the Department of Justice, and after decades of corporate reorganization, it left the Holmdel complex in 2007. After a developer nearly demolished the building, it was remade into a mixed-use building by Somerset, Alexander Gorlin Architects, and NPZ Style + Decor in 2013. The rechristened “Bell Works” welcomed its new tenants in 2016.

Bell Labs was meant to look futuristic in the 1960s, and still does. Hindle and his team used visual effects to strip back changes to the building that the 2013 renovation introduced, like signage, and switched the gold carpet to the Lumon green. “We had to take away all of the personality that was inflicted on the building over the last 30 years,” Hindle says. There are only a few scenes where the real architecture of Bell Labs is used in the show: We have a dramatic aerial view of the exterior and see the atrium when Mark is arriving at work and a shot of its parking lot when he leaves and discovers a note on his windshield explaining why he injured his head. (The note was a lie.) The atrium makes another appearance when Helly R. (who turns out to be the daughter of Lumon’s CEO) receives her brain implant. Beyond these scenes, however, most of the show was shot on three sound stages in New York. No actual building could stand in for the “severed” floor where the microchip-implanted employees work, with its labyrinthine hallways, hyperspecific proportions, and the meticulous details the story required. Hindle knew he’d have to do a build out like Jacques Tati did for Playtime, a 1967 comedy about living in the modern world that was another influence. Still, the show’s interior aesthetic is fully indebted to Saarinen. The illuminated coffered ceiling in MDR is a dead ringer for the one in the lobby of GM Tech, a building he completed in 1955.

Many of the details in the Lumon offices are markers of theoretically “good” workplace design, but have a disquieting effect in the show. Greens and blues are supposed to be soothing colors, but the Macro Data Refinement office’s deep-green rug (inspired, Hindle says, by Oscar Niemeyer’s use of vibrant, monochromatic carpets) feels like a forcible imposition of “Serenity Now.” The office vending machine only dispenses healthy food packaged in plain, uniformly shaped pastel boxes with Helvetica labels. How unappetizing. The stark, blindingly illuminated white hallways are disorienting places to be, as if to say: You shouldn’t be here; just stay in your office. I nearly lost it when Mark visits Wellness, a room where therapylike sessions take place, which is paneled in dark wood, has birdsong piped in, and a tree illuminated by a skylight grows from the floor. The natural world is a reward for the innies. I can picture an interior designer pitching this concept to the Apples and Facebooks of the world.

There’s one detail in Severance that exemplifies the tension between Lumon and its relationship to its employees: the seats in the waiting area by Wellness. There, Hindle set the backs at 90-degree angles and made the seats too shallow to sit at ease. “It’s the most uncomfortable space — I’m not coming here to hang out, I’m just walking through,” he says. “We use those same tricks as designers, just heightened a little bit because Lumon is experimenting on these people.” It’s a fitting parallel to all of the amenity-filled, ergonomically furnished, performance-optimized offices of today. They’re designed to make you feel a certain way, or, at least, nudge you to do what your employer wants. The microchips, thankfully, are still out of bounds.