In November 2018, a wall of flames 14 miles wide hopped the 101 freeway in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley, ripped through the canyons of the Santa Monica Mountains, and charred a path through the hillside mansions of Malibu all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The Woolsey Fire destroyed 1,600 structures, burned nearly 97,000 acres, and caused $6 billion in damage, making it the most destructive fire in L.A. County history and the 30th wildfire in the city of Malibu in 90 years. Speaking at the first city-council meeting after the fire started, Malibu’s mayor, Rick Mullen, who had worked as a captain for the L.A. County Fire Department, said his top priority was to rebuild as quickly as possible. As flames were still eating the chaparral and wealthy Malibu homeowners began asking why firefighters had failed to save their cliffside estates, Mike Davis reiterated the 20-year-old thesis of “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn” from his book The Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster: “I’m infamous for suggesting that the broader public should not have to pay a cent to protect or rebuild mansions on sites that will inevitably burn every 20 or 25 years. My opinion hasn’t changed.”

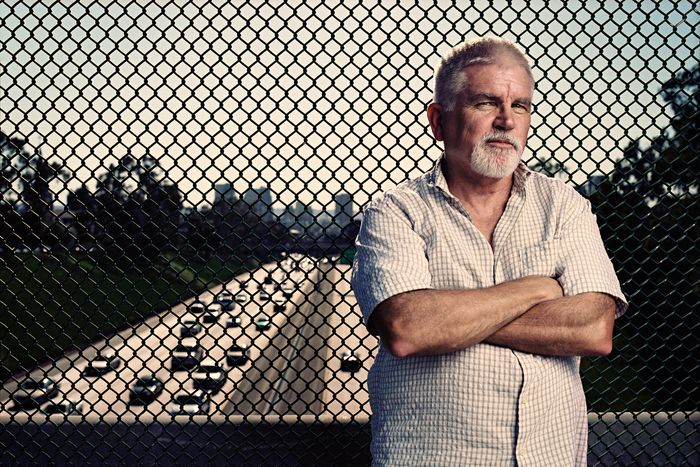

Davis, who died of complications from esophageal cancer yesterday at 76, served as both the reluctant prognosticator-in-chief for L.A. and a guide to the overlapping urban crises that now cascade across U.S. cities with alarming frequency. In his immensely influential 1990 book City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Davis dispenses with L.A.’s typical dichotomies — sunshine and noir, utopia and dystopia — yet provides the first clear framework for understanding the city’s blistering inequality: “spatial apartheid,” wherein white single-family homeowners collude with developers and law-enforcement agencies to banish and criminalize the city’s Black and brown, working-class, and poor residents. The oft-cited chapter “Fortress L.A.” is a wry tour of how this carceral urbanism manifests in an unwelcoming civic landscape, and it provides a visual explanation for why so many places that Americans design, from malls to schools, also feel like jails. On the cover of the book, symbolically, is a federal prison that occupies some of the best real estate in downtown L.A.

Born and raised in suburban Southern California, where working as a truck driver drew him to the labor movement, Davis was an activist historian with an unapologetically Marxist bent. Yet even among those who don’t find their views politically aligned with his, Davis’s books have remained required reading for Angelenos. City of Quartz and The Ecology of Fear are best read together as kind of a one-two punch that lets the history of L.A. splay across two volumes — the construction of a megalopolis that’s an ecological disaster destined to be surrendered to either an earthquake or an impending climate crisis that the city’s leaders have no urgency to address. Some of the assessments (the lionization of Frank Gehry and the homestead as bunker) haven’t aged well. But what’s shocking — or perhaps not so much, once you learn how exactly we got here — is how little the physical L.A. has changed since Davis made his initial observations: The city remains mostly asphalt and concrete, there are few trees and parks, and there’s still nowhere to sit.

Picking away at L.A.’s sheen when the city was desperate to rebuild its image after the 1992 uprising and the 1994 Northridge earthquake meant Davis was seen as a liability. His writing “exposed L.A.’s social fractures and disquieted its most ardent boosters,” as Carolina Miranda wrote in the Los Angeles Times, and the boosters retaliated. Critics who were furious at him for shattering the glittery artifice were eager to point out his factual errors, most of them minor, some of them less so. Writing about L.A. had generally been deemed unserious, but when Davis came along, his takes were too serious. The New York Times, customarily obtuse about anything California, was blithely dismissive of Davis’s description of L.A. at face value: “It’s all a bit much.”

During the past few years, Davis’s words, always prescient, have proved ever more so. The climate disasters arrived with regularity, as promised. His book Planet of Slums traces how those disasters exacerbated poverty for the billion people worldwide who live in informal housing. And then came the pandemic — which Davis has also written a book about, of course. (Jon Wiener, writing Davis’s obituary for The Nation, argued that Davis was not so much reading the writing on the wall as reading the right white papers: “When he wrote about climate change or viral pandemics, he was not offering a ‘prophecy’; he was reporting on the latest research.”) Still, a nearly 800-page behemoth that Davis wrote with Wiener, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, about a city on the precipice of the Watts Rebellion, was published in another strikingly synergistic moment — just weeks before George Floyd was murdered by police, plunging the country into another chapter of civil unrest. Unlike Davis’s previous books, though, Set the Night on Fire is filled with page after page of examples in which Angelenos managed to overcome the spatial apartheid (however tenuously), founding radical art spaces, organizing school walkouts, and — the most essential L.A. challenge — fighting to keep people housed in a city that now has the largest unsheltered homeless population in the country.

Letting Malibu burn (literally or metaphorically) is sound climate and housing policy, but it’s only part of what Davis proposes in that essay. Highlighting the disparities between coastal and inland L.A. — higher Westside rents buy a microclimate that makes life at the beach 20 degrees cooler — Davis compares a 1993 Malibu blaze with another horrific fire that same year in an apartment building in L.A.’s Westlake neighborhood. There, dozens of families, mostly Central American immigrants, were unable to escape their overcrowded apartments. Babies were thrown out of third-story windows by parents trying to save their lives. Ten people, including seven children, were killed. Like the fires in Malibu, fires such as this kept happening in Westlake, too, but for different reasons, writes Davis:

The two species of conflagration are inverse images of each other. Defended in 1993 by the largest army of firefighters in American history, wealthy Malibu homeowners benefited as well from an extraordinary range of insurance, land use, and disaster relief subsidies. Yet, as most experts will readily concede, periodic firestorms of this magnitude are inevitable as long as residential development is tolerated in the fire ecology of the Santa Monicas.

On the other hand, most of the 119 fatalities from tenement fires in the Westlake and Downtown areas might have been prevented had slumlords been held to even minimal standards of building safety. If enormous resources have been allocated, quixotically, to fight irresistible forces of nature on the Malibu coast, then scandalously little attention has been paid to the man-made and remediable fire crisis of the inner city.

It may not be a fire next time — that earthquake, guaranteed, is still somewhere on the horizon — but for a city in crisis, which L.A. certainly is, Davis’s words are a mandate. In a postscript appended to the essay after the Woolsey Fire in 2018, Davis describes the diverging futures of the two L.A.’s in the most dire terms: “Those who can afford (with indirect public subsidies) to rebuild and those who can’t afford to live anywhere else.”