This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

For a minute there, things looked grim for New York City landlords. The pandemic caused an exodus of such proportions that building owners were forced to cut rents to their lowest levels since the bad old days of 2011. But then a miracle happened. (Or at least one seemed to!) Not only did New York’s expats return; they came — in the eerily identical words of the real-estate industry and the credulous reporters who cover it — “flooding back.”

“What started as a trickle earlier last year has become like a geyser of demand,” exclaimed one broker in early 2022. Suddenly, there were lines around the block for open houses and bidding wars over unrenovated walk-ups. The vacancy rate in Manhattan fell below 2 percent, and median rent passed $4,000 for the first time. “I’m not exaggerating when I say that I’ve never seen the rental market as crazy as it is right now,” said another broker in July, right before prices went up again.

What could explain it? Even if all of New York’s deserters had soured on country living — like the publicist profiled by the New York Times who came crying back to Harlem after beavers flooded his yard in Saugerties — that still wouldn’t account for why there seemed to be fewer apartments available than before they’d left. Real-estate experts tried to identify factors that might be aggravating the shortage. Maybe the Fed was discouraging home sales with higher interest rates, so more people were renting. Or the couples that had split up during lockdown were separating and moving into all the one-bedrooms. Or single people had gotten claustrophobic and were spreading out into all the two-bedrooms. Or remote workers from other cities were coming to New York just because they felt like it.

Whatever the cause, the crunch left renters with two options: Pay through the nose or leave. Tenants who had scored pandemic discounts got renewal letters demanding double. Those seeking new places were advised to offer above asking price (i.e., “cuck money”) on apartments they hadn’t even seen in person but that nevertheless included outlandish broker fees and abased themselves accordingly. If they didn’t, they were told, plenty of other chumps would.

In other words, New York City — which in the first pandemic summer had been declared “dead forever” — was back! As long as you had not personally been ejected from your home, you might have even found it inspiring.

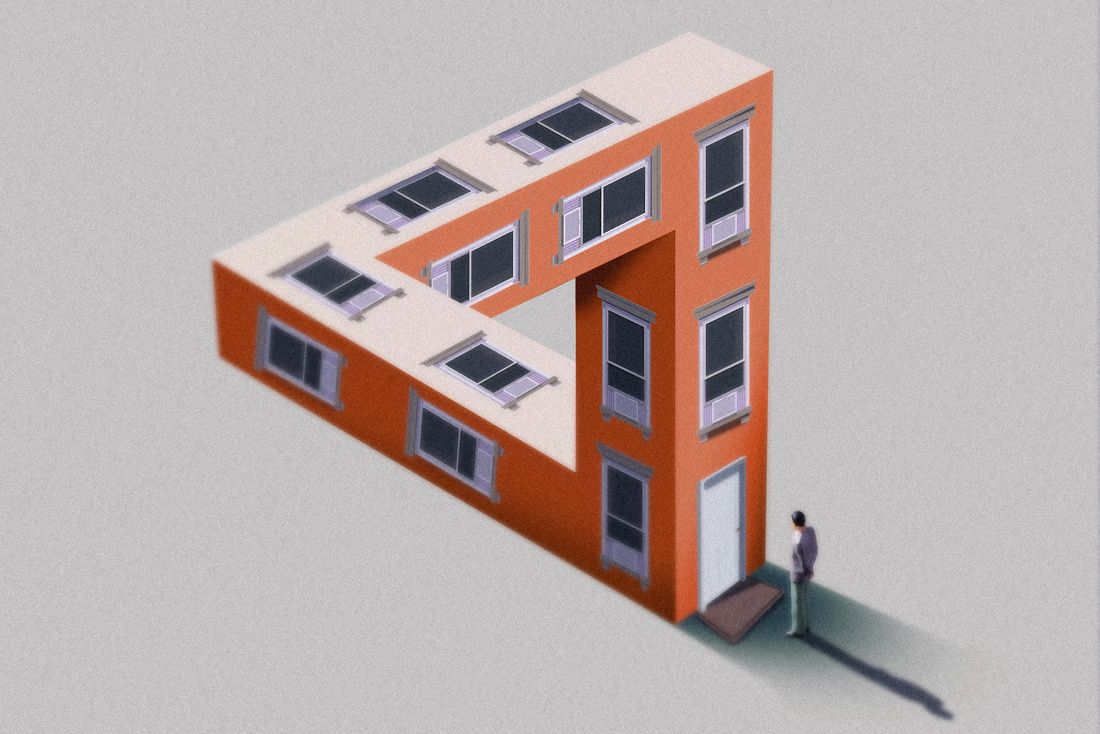

There was only one problem: None of it made any sense.

In late 2021 and early 2022, when demand for apartments was supposedly accelerating from trickle to geyser, New York was still besieged with COVID-related troubles. Return-to-office plans had been quashed by the Delta variant, then Omicron. Tourism was way down, and unemployment was twice the national rate. Crime was reportedly surging — people were getting shoved onto subway tracks — and outdoor dining had emboldened rats to live freely and openly among humans. Had all of the people who had presumably moved to escape these very concerns really come flooding back?

With every rise in the city’s median gross rents, my skepticism grew. I had lived happily in New York for more than two decades, through many disasters and rebounds, and I wanted to believe the story of its glorious post-COVID recovery. But why did it seem like all of the people telling it were also trying to lease me overpriced apartments?

I began to pick up faint dispatches from a distant, numbers-based reality, where a more plausible counternarrative was taking shape. “Manhattan Lost 6.9% of Its Population in 2021, the Most of Any Major U.S. County,” said a March 2022 headline. “NYC’s Population Plummeted During Peak COVID — And It’s Still Likely Shrinking,” said another from a couple months later. According to these stories, New Yorkers hadn’t come flooding back at all. In fact, they were probably still leaking out.

If that was the case, then the city’s rental frenzy defied not just laws of supply and demand but also conservation of mass. All of the people who fled the city over the past three years should have left behind a surplus of empty, habitable apartments. What happened to them? And why is it so difficult and expensive to lease one now?

The Exodus

While I am not technically a statistician, I do pay $7 a month for Microsoft Excel, and over the past year I’ve become somewhat obsessed with the U.S. Postal Service’s database of change-of-address requests, which tracks — across massive, laptop-choking spreadsheets — the number of people who forward their mail to and from every U.S. Zip Code each month. (Extracting just the data I wanted was a weeklong chore that involved filtering out all non-city Zip Codes including, most annoyingly, Nassau County’s, which are intermixed with those from Queens. But I think I got all of them.)

As you’d expect, USPS stats show that lots of New Yorkers skipped town during the pandemic. Between March 2020 and December 2021, there was a net loss of 317,107 permanent movers from across the five boroughs. In July 2020 alone, when moving companies were reportedly so busy they had to turn away customers, a net 25,439 movers left the city. Outbound migration has slowed since then, but it hasn’t changed direction. By my count, the city lost another 97,794 in 2022, ranging between about 6,000 and 11,000 per month.

But that’s not all, because New Yorkers were leaving before COVID. Change-of-address stats show there have been more departures than arrivals in every month since at least June 2017, the earliest month for which I was able to find data. Between then and December 2022, USPS data says 2,878,212 came to the city and 3,548,982 bailed, for a total net loss of 670,770.

Admittedly, change-of-address data is not a perfect gauge. Some business moves are sprinkled in. It captures moves to other countries but misses those to the city from abroad. (The Census Bureau estimates the city gained 33,818 international movers in 2019 but probably less in 2020 and 2021 owing to COVID-related travel bans. Last year saw the arrival of 40,000 asylum seekers.) It doesn’t track deaths (there were over 44,000 from COVID alone) or births (negligible for my purposes, since babies can’t rent apartments, at least not without guarantors). It can’t tell us how many movers within the city took up with roommates or got their own places. It doesn’t distinguish between renters and owners, although elevated outflows in summer months seem to imply many are leaving when their leases expire. And obviously it only includes people who remember to forward their mail, but we can probably assume movers are forgetful in both directions.

But while USPS data can’t give an exact count of how many people are in the city right now, it’s still a solid indicator for broad migration trends. It agrees directionally with the Census Bureau’s estimates, which show that the city’s population has been shrinking since 2016. And it correlates with other metrics such as declines in public- and private-school enrollments (down 9.5 and 3.6 percent, respectively, since 2019), subway ridership, and restaurant patronage.

If there had been any drastic surge in return traffic to New York in 2021 and 2022 — if all of those real-estate experts were telling the truth — it should’ve registered at least a blip in the USPS stats. After all, if so many movers had remembered to change their addresses on their way out, surely most of them would’ve remembered to change them on the way back, right? Instead, USPS data merely shows a gradual return to 2019-size losses.

The Phantom Rebound

Even so, there are many undercurrents to New York City migration, and it’s possible that the USPS data could’ve missed some rogue influx. So with an open mind, I looked far and wide for statistical evidence — besides soaring rent prices — of a rebound in 2021 and 2022.

In August 2021, the Census Bureau announced that its 2020 count had found more people living in New York (8.8 million) than in 2010 (8.2 million). A few tried to spin the results as a sign of the city’s COVID-era resilience, including Mayor de Blasio (“The Big Apple just got bigger!”), but, alas, the numbers had been tallied only a few weeks into the pandemic and all gains had come pre-2016. Then the bureau announced that New York City lost 305,000 residents between July 2020 and July 2021 (which is more than USPS stats show for the same period) and that the 2020 U.S. Census had overcounted the population of New York State by an estimated 695,000.

In November 2021, the New York City comptroller issued a widely circulated report on pandemic migration, which cheerfully asserted that “since July 2021, USPS data has shown an estimated net gain of 6,332 permanent movers, indicating a gradual return to New York City.” I checked and double-checked the USPS data and couldn’t find those movers, so I asked the comptroller’s office to explain. A spokesperson directed me to an updated chart, buried in the middle of an October 2022 newsletter, but it showed no bump in 2021, just continued bleeding.

In June 2022, Bloomberg.com ran a feel-good story headlined “More People Are Moving to Manhattan Than Before the Pandemic,” which cited a report by the data firm Melissa. Melissa’s rose-colored analysis appears to hinge on USPS stats showing more permanent movers entering the borough between March 2021 and February 2022 than had in the year leading up to the pandemic. But that obscures the fact that by December 2021, monthly move-ins fell back below pre-pandemic levels and stayed there for all of 2022. Most important, according to USPS data, Manhattan’s net migration was still negative for the entirety of 2021-22.

I was intrigued when a company called Placer.AI published a study this past summer that found Manhattan’s population had recovered its pandemic losses, then followed it up this month with a claim that the borough is now 3.9 percent more populous than it had been in 2018. But the start-up’s core business is analyzing mobile data to estimate foot traffic for retailers, not measuring who lives where. I asked Ethan Chernofsky, the company’s VP of marketing, how sure he was of his findings. He told me that because Placer.AI is mindful of privacy concerns relating to location data, “we very aggressively remove our ability to estimate residential well.”

I called more than a dozen New York moving companies, including tristate and national ones. They all told me they’re still moving more people out of the city than into it. And I spent a long time trying to make sense of data from the New York City Water Board, which shows that the amount of waste treated by the city’s processing plants jumped in 2021. (Maybe everybody had shit their pants when they found out how much their rent was going up?) But it turns out those plants treat not just human waste but stormwater too, and 2021 was rainier than usual. At least I think that’s the reason — the Water Board quit returning my emails after a while.

Actually, a lot of city employees stopped returning my calls and emails. I started to get the feeling that they were wary of acknowledging what seems like a pretty clear trend of negative migration. One source told me it might not be my imagination: “I think policy-makers do have an interest in downplaying the population-decline story. Federal resources are allocated based on U.S. Census numbers, and they want those resources to be as great as possible and deployed to their districts.”

The Inventory

In 2017, I moved to a new rental tower in Downtown Brooklyn into what the leasing agent promised me was the very last available one-bedroom. But after living there a couple months, I began to get suspicious. I was the only person in the gym most mornings. And there was surprisingly little competition for washing machines in the laundry room. There were more than 500 units in my building — were all of my neighbors sedentary nudists?

One night, on my way home from work, I pushed the wrong elevator button and got out on the floor below mine without realizing it. My key wouldn’t fit the lock to what I had assumed was my door, so I turned the knob and stepped, to my astonishment, into a completely empty, totally untouched one-bedroom. I turned around and beelined to the elevator, worried that I’d get busted for trespassing, when I noticed strips of masking tape covering the door frames on all of the other (presumably empty) apartments on the floor.

This was how I became aware of “warehousing,” the practice by which landlords keep unrented apartments off the market to create artificial scarcity. Building owners have always done this, especially in new constructions with lots of virgin inventory, because why give renters the upper hand if they don’t have to?

But they really started doing it during the pandemic. On a 2022 episode of the real-estate-industry podcast Talking Manhattan, Gary Malin, COO of the Corcoran Group, made a surprising claim: “At one point during the downturn, the vacancy rate in the city was close to 25 percent,” he said. “You had owners who were sitting on hundreds if not thousands of empty apartments.”

Officially, during the peak of the COVID exodus, the vacancy rate in Manhattan was 4.3 percent, the highest in at least 14 years. But those “official” vacancy rates we hear so much about are sourced from market reports by brokerage firms like Corcoran and Douglas Elliman, and they only reflect the number of rentable apartments that landlords are advertising, not the number that actually sit empty. Given the incentives for underreporting, this is a little like calculating a city’s crime rate by asking criminals how many people they robbed and murdered last month.

I asked Malin to estimate the real vacancy rate post-rebound. “I think it’s close to 2 percent,” he told me, which would put it back in line with official rates. “Unless an owner is intentionally keeping units off the market for whatever their reasons — maybe they need to do renovations, maybe they plan to sell the building and think it’s better to sell it vacant — right now, if you have apartments available, you are renting them.”

Still, a 23-point drop in New York City’s vacancy rate would signal an inflow of hundreds of thousands of residents who haven’t yet appeared in any other data. Where are they? Or, perhaps more pertinently, if building owners were lying to us about the amount of their unused inventory as recently as a couple years ago, why should we believe them now?

We know that at least 20,000 rent-stabilized apartments are being warehoused because landlords have admitted as much. (A 2021 Census Bureau estimate puts the number at 42,860.) Owners blame a 2019 state law, the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, which limits the amount they can raise rents to pay for renovations. They say their warehoused apartments are in such poor shape that it would be impossible to recoup the cost of necessary repairs at rent-stabilized prices, so they’re holding them vacant until Albany repeals the law.

“Some of these apartments had been occupied for 20 or 30 years,” says Jay Martin, executive director of the landlord group the Community Housing Improvement Program. “They need gut renovations. Some have asbestos in them, some have lead.” But Linda Rosenthal, chair of the New York State Assembly Committee on Housing, is dubious. “I went into one of those units,” she tells me. “Turns out it needs a coat of paint, maybe a new bathroom sink.” (Rosenthal has proposed the End Warehousing Act of 2021, which would impose penalties for holding apartments vacant for longer than three months.)

Whomever you believe, it reflects badly on just about everybody that there are tens of thousands of empty rent-stabilized apartments in a city where more than 100,000 people slept in homeless shelters last year. But this is only one factor in New York’s rent-affordability crisis, and mothballing these units probably isn’t what sent the price of market-rate Manhattan one-bedrooms spiraling toward infinity. “These stabilized units are a completely different product,” says Martin.

The Dark Towers

I’m extremely curious about all the high-end rental buildings that have sprouted in Manhattan and rezoned neighborhoods like Downtown Brooklyn, Williamsburg, and Long Island City over the past decade. Many of these buildings went up around the same time — to take advantage of a popular tax break that expired in 2022 — creating an oversupply of so-called luxury units that were too expensive for most normal New Yorkers. For years, owners of these buildings were forced to offer concessions like rent-free months on their leases. (Although, to be fair, they were doing a bit less of this by February 2020, just before the pandemic.)

I spoke to one moving-company dispatcher who recalled making a deal with the management of a Downtown Brooklyn tower about becoming that building’s preferred service when it opened in 2017. “We were jazzed. They promised us all this work, and we hired more guys to cover it,” he said. “We jumped through all these hoops, but then we only got two or three jobs out of it. Nobody was moving in.”

It was the neighborhoods with these expensive high-rises that saw some of the city’s steepest peak-COVID population losses, and the people who fled were probably the types most likely to rent in them. According to IRS data, New York’s pandemic deserters had average incomes that were 28 percent higher than residents who stayed. One new rental tower in the Financial District reportedly saw occupancy drop 24 percent in 2020. And yet, somehow, by January 2022, the glut was gone as prices in luxury buildings reached all-time highs.

I have no proof that apartments in these towers are being warehoused and acknowledge that such a thing may seem counterintuitive in today’s allegedly red-hot market — or any market. But if demand for expensive units is softer than we’ve been led to believe, I wonder if landlords could be hiding supply to keep their rents up. Why not just list all of their vacant apartments, even if that depressed prices, since collecting some rent is better than collecting none at all? Maybe because owners take out large loans to develop these buildings, and their lender agreements often require that they charge minimum amounts. This is also the thinking behind the deliberately confusing “net effective rent” scheme whereby an apartment’s advertised price includes prorated rent-free months to soften the blow of its actual (potentially lender-mandated) asking price.

But here, I admit, is where my conspiracy theory falls apart: If all of these luxury buildings were hiding supply, wouldn’t one smart landlord undercut competitors by opening their whole stock and making a killing at today’s artificially inflated prices? Of course one would. And so I almost ended this column with a deeply felt apology for impugning the honest intentions of the New York City real-estate community.

The Algorithm

But then, in October, ProPublica published what seemed like evidence of an actual conspiracy. It turns out that some landlords have been using the same software to do some very interesting things.

The app is RealPage Revenue Management Software, it’s made by the Texas-based company RealPage, and allegedly it works by collecting private pricing and inventory stats from competing building owners and then using that data to give them each recommendations for how to price their available apartments such that nobody undercuts the others.

Some argue — including the plaintiffs of over a dozen class-action lawsuits filed in the wake of ProPublica’s story — that RealPage’s software allows individual landlords to keep their hands clean while indirectly colluding to inflate prices. In 2021, a RealPage executive bragged at a conference that his company’s algorithm was responsible for rent increases nationwide. “I think it’s driving it, quite honestly,” he said, according to the article. “As a property manager, very few of us would be willing to actually raise rents double digits within a single month by doing it manually.”

Landlords are allowed to reject RealPage’s pricing guidance, although former employees of the company told ProPublica that up to 90 percent of suggestions are followed. The software discourages negotiation with tenants and has even been known to tell owners to goose prices by holding back supply.

On a 2017 earnings call, RealPage CEO Steve Winn described how a property manager saw revenues go up when their buildings that had historically been 97 or 98 percent full cleared out to 95 percent, “an occupancy level that would have made management uncomfortable before.” According to one lawsuit, “This is a central mantra of RealPage, to sacrifice ‘physical’ occupancy in exchange for ‘economic’ occupancy, a manufactured term RealPage uses to refer to increasing prices and decreasing occupancy in the market.”

RealPage’s algorithm was designed by a guy named Jeffrey Roper, who was the director of revenue management at Alaska Airlines in the 1980s, when that airline and others developed software that led to a price-fixing settlement with the Department of Justice in 1994. (The DOJ is now reportedly investigating RealPage.) Compared to RealPage, human property managers have “way too much empathy,” Roper told ProPublica.

Based on their delightfully candid comments elsewhere, it’s probably no wonder that RealPage’s press department declined to let me speak to any of the company’s executives. But a spokesperson told me in a statement, “Rent prices are driven primarily by supply and demand, and in New York, vacancy is very low, causing rents to rise.” RealPage’s own website, though, touts its “proven, cycle-tested, disciplined analytics that balance supply and demand to maximize revenue growth.”

The spokesperson also tells me that RealPage software is only used by property managers of approximately 1.8 percent of New York City rental apartments, but given the city’s estimated total stock of 2,274,000, that might span 40,932 units. And depending on what types of apartments those are and where they’re located, coordinating to set their prices could scramble market dynamics beyond just directly comparable homes. RealPage-driven rent hikes on higher-end rentals could push prospective tenants of those units to seek more affordable options, raising prices on the middle end.

It’s hard to know who all of RealPage’s customers are, but Greystar, the biggest property manager in the U.S., reportedly uses the software to set the rents of 168,000 units nationwide. Greystar’s website lists 25 buildings across Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, all of them full of apartments that are priced as reasonably as you’d expect. Know anybody looking for a $4,647 studio? (Greystar did not reply to repeated requests for comment.)

Look, it’s possible that my suspicions are baseless and all of these buildings are full. Maybe their tenants really did come flooding back to New York last year. Maybe some are former couples who broke up during the pandemic and needed twice as many apartments and others are remote workers from Milwaukee or Akron evading city taxes by claiming residency in their old states. Maybe they came without any furniture so they didn’t have to hire movers. Maybe they’re homeschooling their kids, taking Ubers instead of the subway, avoiding restaurants, and abstaining from all other activities that would expose them to public data collectors. Weirder things have happened here. But if you meet any of these people, give them a change-of-address form for me. They’re probably missing some good mail.

More on the housing market

- Steve Cohen’s Mega-Mega-Mansion Is Now Visible

- Settling, in Downtown Brooklyn

- That $8,000 Two-Bedroom Comes With a Week of Summer Camp