The Flatiron Building is up for sale today, and if you can show up at Mannion Auctions on lower Broadway with a solid nine-figure bid, it could be yours. It’s an availability that stems from a long-simmering impasse. Five companies jointly own the Flatiron, four of whose plans for it are more or less aligned. The fifth, Nathan Silverstein, whose father bought 25 percent of the building in 1945, disagreed with them about its future use and imminent renovation — among other things, he reportedly proposed breaking it up into five individually owned units, condo style, which would have been even harder to manage — and after several years’ stalemate, a judge recently ordered that they sell, leading to today’s bidding. (This is the second time the building has been auctioned off amid difficulty. The first was when its owners defaulted on the mortgage during the Depression in 1933.) The buyer will receive it empty save for a ground-floor retail tenant, because one of the things the owners could not agree upon was precisely how to carry out the needed renovations after the last office tenant left.

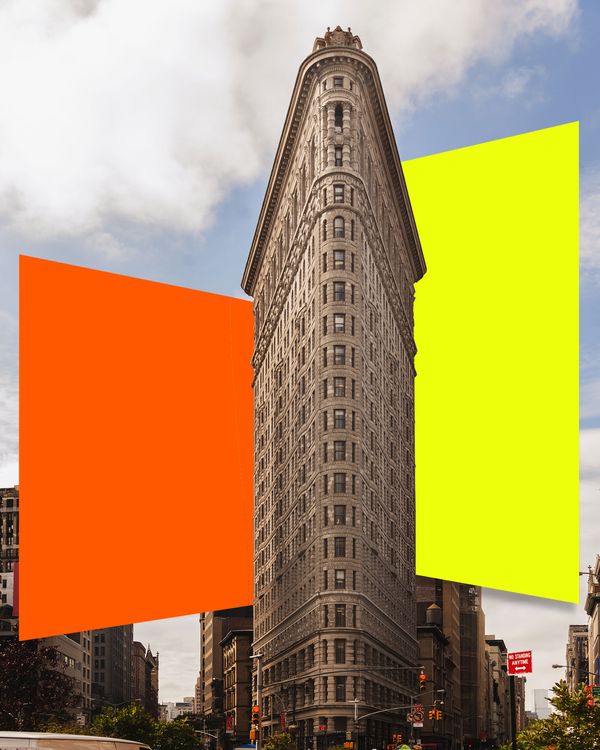

It’s a building that is easy to love from without and trickier to love from within. The Flatiron — officially called the Fuller Building in its early days, though that name never stuck — has been a magnet for photographers since it rose at 23rd and Broadway in 1901, and if you stand across the street from its prow in front of Eataly, you will see Instagrammers and other tourists adding to that countless tally of pictures. Out of its problematically small and oddly shaped site sprung a picturesque monument, one of the first tall steel-frame buildings in New York City. For several decades, starting in 1959, it was the headquarters of an array of book-publishing imprints, eventually owned by Macmillan, which went from renting a small amount of office space to taking over the whole thing. Its editors often remarked that they loved being there, not least because of the generous number of windowed offices around the perimeter of the floors. One of the house’s imprints was even named for the building.

But it also has its downsides. It’s really old, and its distinctive shape makes the subdivision of the small floor plates awkward. Many of those editors’ offices were tiny slivers, typically with room — and I can tell you this from firsthand experience — for exactly one visiting writer on one very small chair, and the ones on the Broadway side of the building had odd trapezoidal layouts. Holtzbrinck, Macmillan’s owner, didn’t spend much on creature comforts, and by the time the firm left, in 2019, much of the space was decidedly shabby. Until the windows were replaced in the early 2000s, the building was notoriously drafty, and well into the 1990s, it relied on the original elevator mechanicals, which were driven by water pressure and were painfully slow on the days when they were working at all. “If you had a meeting, you had to get there a half-hour beforehand,” recalls Verna Shamblee, then Macmillan’s vice-president in charge of facilities. It has 21 floors, but the main elevators go only to 20, so you have to switch for that last run. The men’s and women’s bathrooms are on alternating floors, and most of them are pretty bad. The outside, at least, is in good condition, because its terra-cotta was cleaned of a layer of sooty filth in the 1990s and more recently saw a thorough restoration, and right now it’s receiving further care. It’s landmarked, and any exterior changes have had to conform to strict preservation standards.

Disputes aside, a lot of that interior work has been proceeding: Walls and partitions have been cleared out, three of the elevators have been upgraded again, and (most visibly) the single exit stairwell at the core of the building, grandfathered in and no longer remotely up to code, is being replaced with a pair of twin scissor-style staircases. The building is also getting central air conditioning, which will finally do away with an array of clumsy window units. And there will be a cool opportunity for some lucky tenant: The stairs to a basement space that a century ago held a huge restaurant were uncovered some years back, and according to a Landmarks hearing held in 2021, there are plans to reconstruct an entrance and recover part of that space for retail use. It could make a snazzy little bar.

There has also been talk for years of turning the whole building into a hotel or an apartment building, partly because the very thing that makes this narrow site memorable is also what makes it less versatile as office space. Most first-tier tenants today want a giant open floor plate, not a stack of pie wedges.

So who’s going to get the building? Unless you’re extremely rich and wildly spendthrift, it’s probably not going to be you. Jeffrey Gural, whose family firm, GFP Real Estate, manages the building and is one of the current owners, confirmed that he and the other owners who own three-quarters of the building want the remainder of the pie: “I think everyone recognizes that we intend to bid for the 25 percent.” They are, he added, a little better positioned than outside buyers because they have to come up with only a quarter as much cash as anyone else. If they get it, he says, they’ll then decide what to do: convert it into a hotel, make it into apartments, or try something else. “The easiest thing to do is keep it an office building because we have all the approvals. For a hotel, you need a special permit and it takes awhile — that can take up to 18 months.” But, he adds, you never know how an auction is going to go: “Obviously, if somebody wants to come in and bid $300 million [for the whole thing], that’s up to them.”