In the early days of the war, Bogdana Ferguson felt like her body was being controlled by an outside force. At dinners with friends in New York, she would find herself suddenly getting up and leaving the room when the conversation turned to frivolous matters — something she would only recognize as a subconscious reaction later on. Her friends were talking about NFTs; she was thinking about the massacre in Bucha and worrying about her 54-year-old father, a retired coal miner who had just decided to enlist in the Ukrainian army. Ferguson, 28, is a fashion photographer who moved from eastern Ukraine to New York nine years ago. She loves the work, but after Russia invaded her home country on February 24, 2022, she began to feel how detached her job was from her and other Ukrainians’ new reality. “The fact that the world’s life still goes on,” Ferguson says. “Well, how could it?”

In the year since Russia invaded Ukraine, millions of people living in that country have been displaced, and the U.N. estimates at least 8,000 civilians have been killed, with thousands more injured; although it’s difficult to confirm exact numbers, some government sources believe that the Ukrainian and Russian armed forces have each suffered as many as 100,000 to 200,000 casualties. The war has also brought a jarring sense of dislocation to those in the diaspora — including in New York, the city that’s home to the most Ukrainians and Ukrainian Americans in the country.

Many Ukrainian New Yorkers in their 20s and 30s say the past year had changed how they see their identity and splintered their social lives. The war has led to online fights and unexpected tensions with friends, family, and colleagues — but it’s also led to more connections with other Ukrainians, especially as some have become involved in relief efforts. They know they’re the lucky ones: Unlike the people they know in Ukraine, they can’t hear the air sirens. They have no need to hustle off to bomb shelters. Many will tell you that a form of survivor’s guilt has taken hold — and a constant hum of anxiety.

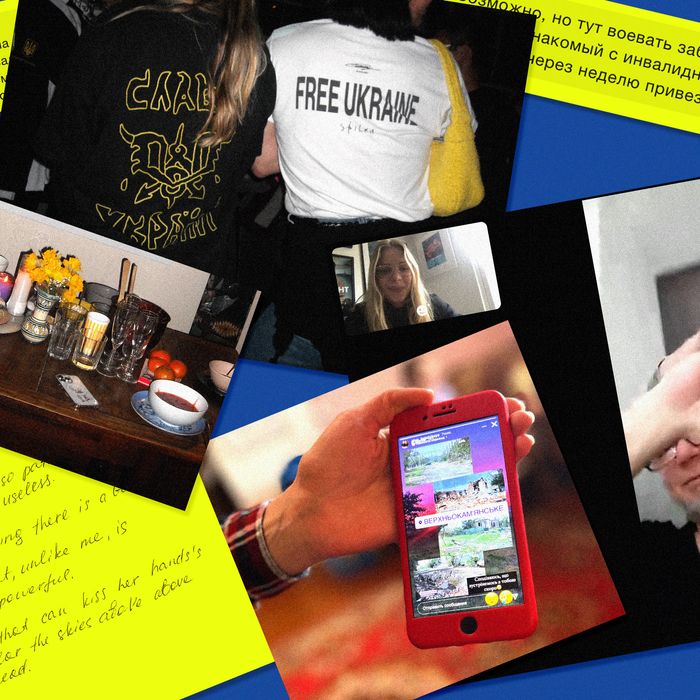

“In Ukraine, everyone knows someone who’s fighting or been killed,” said the writer Megan Buskey. Iva Verba, a student at Brooklyn College who moved to New York City just a few months before Russia invaded last year, volunteers with relief efforts and attends protests but still feels that she is “not doing enough, all the time.” To her, it seemed as if Ukrainians in New York were more anxious than people in Ukraine, a sentiment many shared — and one exacerbated by the seven-hour time difference. “My friends say that they’re safe, but it almost feels like they’re calming me down when they say that,” says Betty Roytburd, a 33-year-old Odesa-born artist and co-founder of the collective Spilka, which was formed after the invasion to support war-relief efforts. “They joke that it’s less stressful for them to be there than to be having to experience this threat from a distance. They compare it to being in the eye of the storm, versus being on the outside of it and being sucked in.”

As soon as Ferguson heard the news last February, she started trying to reach her family and friends in Ukraine. “I waited for their answers, but my body would, like, shut off,” she says. “For quite a few weeks, a lot of people wouldn’t sleep until their families woke up.” Like many Ukrainians, Ferguson says that this war started in 2014 when Russia invaded, then annexed Crimea, and Russian-backed separatists took over swaths of the Donbas region. Ferguson had grown up in the Donbas, in the province of Luhansk, and left it shortly after the conflict began. As she tried to settle into New York, a city where she knew no one, her parents fled their hometown to move further away from the Russian border — to a place where seeing tanks roll down the street was a less common occurrence. With the invasion last February, Ferguson realized her parents were in danger again.

She soon discovered and began volunteering with a group called Helping to Leave, an international network that started as a Telegram group chat aiming to get people out of Ukraine. The work became a full-time job. (Although she notes that the pay she gets from it now “would not even cover my rent.”) Her life splintered in two: There was Ferguson the photographer, who continued to schedule shoots and pose models, and Ferguson the relief worker, who helped to coordinate the evacuation of a Ukrainian soldier captured and tortured by Russian forces and was figuring out the logistics of obtaining a wheelchair for a grandmother who needed one to be able to get on a flight and flee Ukraine.

The disconnect between the two worlds has been jarring. Her social circle in New York has both constricted and widened; she doesn’t see many people other than Ukrainian Americans who have thrown themselves into relief efforts. She’s envious of those who can put the war aside. “It takes a toll on you, but I do not see any other way right now,” she says. “I’m volunteering my time. But people are actually volunteering their lives.”

“There’s very few people who don’t have family on both sides of this thing,” says Sofia, a Brooklynite in her late 20s. “At least for us.”

When she says “us,” she means New Yorkers like herself — people she describes as post-Soviet-era Jews whose families came to the U.S. from Russia or Belarus or, like her parents, Ukraine and Moldova. Sofia, who asked to use a pseudonym, grew up jokingly calling herself “Jewkrainian,” though even that could be fraught. “Especially when it comes to Jews from Ukraine, we’ve never really called ourselves Ukrainian. Historically, we’ve always been separate,” she says. “We’ve experienced genocide at the hands of all these people” — meaning, she says, both ethnically Slavic Ukrainians and Russians. She still flinches when she hears the protest slogan “Glory to Ukraine, glory to the heroes,” a patriotic phrase first used over a century ago. Because of one of those past “heroes,” she notes, “I’m pretty sure at least three of my great-grandparents were orphaned.”

But after Russia invaded Ukraine last year, she began asking herself if she should describe herself as Ukrainian American — a question she says has been common among her friend group. “Specifically for those who are Jewish, there’s been a real reevaluation of who we are and our identity in the wake of all this,” she says. “It was easier, for decades, to call this conflict not our issue. That it was a ‘brother war’ — that Russians and Ukrainians are both Slavs, they can go fight it out.”

That’s changed for her. Early on, her grandfather’s neighborhood in Kyiv was bombed, and her family in New York didn’t hear from him for three days. She’s also seen these shifts play out among her family members in Brooklyn. One day last year, she recalls, “my grandmother took the remote and changed the TV from the Russian channel to the Ukrainian-language channel. And she never changed it back. I’ve never heard her speak Ukrainian in my life — apparently she’s fluent.”

When the war began, Sofia was working for a prominent Jewish social-service agency in South Brooklyn. Her supervisor was a Jewish woman from Kharkiv whose younger brother was unable to leave Ukraine: “I remember my boss looking at me with tears in her eyes and saying, ‘I’ve never really distinguished between Russians and Ukrainians. Now I distinguish them quite well.’”

The war kept spilling over into Sofia’s life. One day at work, she had to intervene in an argument between a Jewish client from Ukraine and a Jewish volunteer from Russia: “The client was just like, ‘She thinks of herself so highly. She’s Russian, and she looks down on Ukrainians.’” Meanwhile, at her grandmother’s senior center in South Brooklyn, the war was “a forbidden topic,” Sofia says. “There had already been fights, like, actual fist-throwing fights.”

Sofia identifies as a leftist and says that over the past year has gotten into her share of debates with other leftists about Russia’s history as an imperialist power, and with those who sneer that she’s a “liberal” when she criticizes Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “People don’t really seem to think that there is colonization because Ukrainians are ethnically similar-looking to Russians,” she explains.

Fights over what to do about the war and what would be most helpful to Ukrainians have become a point of tension for many in New York. Ferguson recalls getting into a heated debate with a former friend about the war, who questioned Ukraine’s desire to join NATO. To her friend, joining NATO was akin to supporting “Western imperialism.” Ferguson remembers her own response: “You’re protected by NATO — you have no idea.”

Roytburd, the co-founder of Spilka, has been similarly frustrated with progressives she’s encountered here. It upset her when the People’s Forum, a local left-leaning organization that calls itself a “movement incubator,” held an event in November called “The Real Path to Peace in Ukraine” and featuring speakers like Jeremy Corbyn, Jill Stein, and Noam Chomsky but no Ukrainians. “I have had several experiences of talking with people who I know believe in Russian conspiracies, like that Ukrainians are persecuted for speaking Russian in Ukraine” — a false claim that Putin has made to justify the invasion. “It just, like, makes me feel more isolated.” (Many Ukrainians speak Russian, both within Ukraine and in the diaspora. Several interviewees noted that they know other Ukrainians who have decided, because of the war, to speak Ukrainian more often instead.)

For everyone interviewed, the question of how to interact with Russian culture — and assumptions about similarities between Russians and Ukrainians — has become a pressing issue. Last year, Verba, the Brooklyn College student, was working as a waitress at a Times Square restaurant when her manager, who is not Russian or Ukrainian, asked where she was from: “I told him that I’m from Ukraine, and he started telling me that my country doesn’t exist and we don’t have our own culture and language and, like, we’re just part of Russia.” Moments like that have hardened her, she says: “I don’t feel empathy for Russian people at all.”

Ferguson said she didn’t have many Russian friends to begin with, but she’s watched her Ukrainian friends sever ties with Russians they know. “A lot of those friends had to shed like ten friends, just because they did not feel any support whatsoever,” she says. “Like, these Russian friends would tell them, ‘Just chill! Why worry? You’re safe here.’” In the cultural sphere, Roytburd says she didn’t think that U.S. institutions should be working with Russian artists at the moment. “I don’t think people realize how violent it is for Ukrainians to see people celebrate Russian culture right now,” she says. “Russian culture has always been Russia’s greatest export, and a tool that delivers the message of greatness of the Russian Empire.”

Some cultural institutions in the U.S. have responded by cutting ties with Russian artists over the past year. Last February, the Metropolitan Opera canceled the planned appearance of a Russian soprano who had previously expressed support for Putin. But Russian artists who are critical of the regime have faced blowback as well — such as when, last March, galleries associated with the School of Visual Arts pulled out of an international exhibition focused on “the repression of Russian artists, journalists, and citizens for voicing their opposition to the war in Ukraine,” after facing criticism that the show was, as one Ukrainian American artist put it, “exploiting Ukrainian pain and flag to promote Russian voices.”

The calls to ban Russian artists don’t sit well with everyone, including Misha Tyutyunik, a 38-year-old muralist and illustrator born in Kyiv and now based in Bay Ridge. (His work has appeared in New York.) To Tyutunik, the problem is Russian warmongers, not artists. “Canceling people because of where they’re from?” he says. “That’s rich coming from Americans.”

He says that the war has had the unexpected effect of bringing more attention to his art — and more tension. Within two weeks of Russia’s invasion, the commissions started pouring in: “Ukraine became the ‘It’ subject. And Ukrainian artists became the ‘It’ artists for a second.”

He appreciated the influx of jobs — he and his partner had a new baby — and rarely turned anything down. His bigger concern was the well-being of his friends and relatives in Ukraine. Just a few weeks before the invasion, he’d been in talks with local government officials to paint a mural in the southeastern city of Zaporizhzhia. On the eve of the invasion, he heard from his contact there: “He was like, ‘Unfortunately, we just went into martial law because supposedly Russia is invading.’” Zaporizhzhia, and its nuclear plant, would soon be on the front lines.

At times, he says, the attention from American clients felt “a little exploitative,” like people were hiring him to burnish their liberal bona fides because he had “Ukrainian-born” in his Instagram profile. He thought that this must be how Black artists felt during the protests after George Floyd’s murder. He bristled when people would tell him that he was a “shoo-in” for a project because he was Ukrainian. He wondered: Did his clients even like his art or value it for its artistic merits? And where were all these people in 2014? “You didn’t care about Ukraine a year ago,” Tyutunik says. “It makes you feel othered, in a way.”

He has struggled with walking the line between supporting Ukraine and its people and the easy villainizing of Russians. Last spring, after the war began, Tyutunik had a solo show at an uptown gallery titled “Kyiv,” featuring paintings that had been inspired by his time in the capital city. One day at the gallery, an older man, who was not Ukrainian, proudly told Tyutunik that on his way there he had walked by the Russian embassy and told someone standing outside to “go fuck himself.” Tyutunik was startled that the man seemed to think he would be happy to hear he had cursed out a random stranger.

“I was like, ‘What? Man, why would you do that?’” he recalls. “I think he wanted to show solidarity. But fighting with no knowledge behind it is just dangerous.”