Penn Station is a terrible place — about that nobody’s arguing. Getting all the parties to agree on how to make it better, though, is less like herding cats than like herding herds of cats. Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and the MTA all have their separate lairs inside the the labyrinth, Madison Square Garden presides above, the development company Vornado owns much of the property all around, the state has partial jurisdiction, and the money to do anything would come from an assortment of lenders and government agencies. It’s a perfect recipe for infinite postponement. But something may be coming unclogged. The Italian infrastructure company ASTM and the architecture giant HOK, which is working on a fresh design, has recruited Vishaan Chakrabarti, founder of the boutique architecture firm PAU, to its side. That might seem like a minuscule shift in a big landscape, but it has a spark of significance.

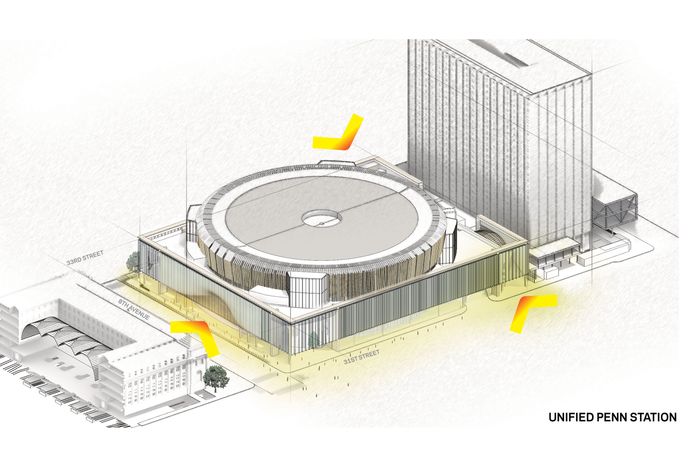

Chakrabarti came to wide attention back in 2016 for a speculative design that envisioned prying Madison Square Garden from its perch atop Penn Station and recycling the circular frame as the skeleton for a new light-filled train hall. He’s always insisted that moving the Garden was key to a worthy Penn Station—until now. The details are still being worked out, but broadly, the ASTM/HOK plan would demolish the 5,000-seat theater that now clings like a barnacle to the Garden’s underside and hangs down into the station. That would clear the way for a grand Eighth Avenue entrance and a wavy, high-ceilinged train hall with daylight, views, direct platform access, and clear, actually legible signage. A wide concourse would lead to another, more modest hall closer to Seventh Avenue. Smoother crowd flows would alleviate the acrid rush-hour tang of claustrophobia and panic and allow the place to handle even more passengers. (It would do nothing to add more trains to the schedule, though.) Crucially, all of that would leave the rest of the arena above undisturbed.

“I always said that I’d be willing to consider leaving Madison Square Garden alone if you could show me how to make a great station without moving it. This plan does that,” Chakrabarti said. The architect has no political or financial control over the future of the station, but his defection from the dwindling get-rid-of-MSG camp carries a certain moral weight. It broadcasts the possibility that a good compromise, if not a perfect solution, really does exist. “Our design had a 150-foot ceiling. This one has a 55-foot ceiling, but that’s a lot better than ten feet, which is where it is now,” he said. Chakrabarti insists he’s not just bowing to a disappointing reality but rather throwing himself into the most promising version of a future Penn Station that he’s seen: “If you can’t beat them, turbocharge them.”

One immediate consequence of that move is that it may encourage the City Council to renew the special permit, expiring this July, that Madison Square Garden needs to operate. The council already did so once, in 2013, giving the venue a ten-year window in which to find a new location. The Garden ignored that deadline, gambling that legislators would never force the issue. Now, the council may be off the hook.

There’s still plenty of murk in the offing, though. Governor Hochul remains nominally committed to a terrible and seemingly moribund urban-renewal-style plan that would pay for the rehab with a cluster of enormous office towers. The MTA is plowing along with its own master plan, which does not involve excising the theater. For now, the ASTM proposal is still just an idea floated by a private company that has no claim to the site and no political backing. But the company does have several aces in the hole. It comes to the project bearing $1 billion in its own seed money, enough to buy the theater and start construction without having to wait for all the other sources of financing to align. It’s also put in two years of engineering work fleshing out conceptual designs with a high degree of technical specificity. It’s promised a lower price tag for the whole project (though how much lower is still unclear) than the current $7 billion estimate. Amtrak, NJT, and the Garden — each of which has different logistical requirements — have signaled that they’re amenable to the proposal, leaving the MTA as the main dissident holdout. The cats are falling into line.

With Chakrabarti now onboard too, ASTM says it plans to release a more fine-grained design and more financial details within the next couple of months — at which point, it could still join the towering stack of discarded plans. Whether it does or not, you’ll be reading about it for years to come.