It was late in ’64 when I finally had a little income that I decided, Okay, now I can get rid of Mother’s castoffs,” says Andrew Alpern on a tour of the one-bedroom co-op in the Penn South middle-income complex in Chelsea he’s lived in since 1962, when it was new. “And I went to B. Altman” — the long-gone department store whose genteel building still stands on 34th and Fifth — “and bought that couch you are sitting on. I paid $468, on sale, which back then was a lot of money.”

Alpern, 83, often digresses in the course of conversation, one thing leading to another that reminds him of any number of references and stories relating back to his original topic, because he is an expert in excavating the history of life in this city, where he has lived all his life (as did his parents).

Alpern grew up on West 82nd Street. He went to Columbia University, where he studied architecture; as a student, he bought this sensible 17th-floor apartment when it was still being built. After working as an architect for more than 20 years, he had a second career as a lawyer. But he is well known for his 11 books on Manhattan’s architecture since around 1860 and has written about, among other subjects, Rosario Candela’s buildings and the Dakota. (His most recent book, Posh Portals: Elegant Entrances and Ingratiating Ingresses to Apartments for the Affluent in New York City, was published in 2020.) He’s written them all while living in Penn South, which was sponsored by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, where resale prices are capped, as are the incomes of buyers, in order to maintain affordability. (There is a long waiting list.) Meanwhile, the blocks around it, especially adjacent to the High Line, have become home to some of the fanciest buildings of our current Gilded Age.

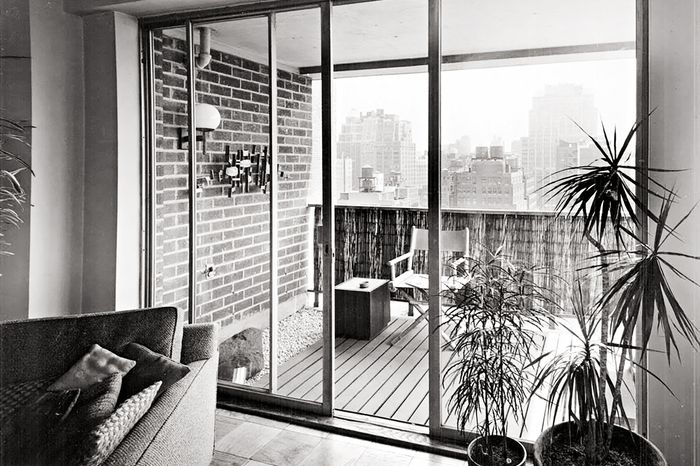

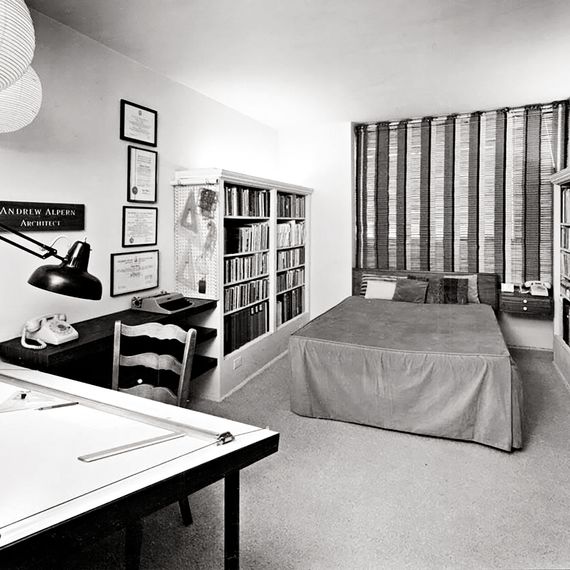

Alpern paid just $3,000 for this apartment. When he moved in, he took down — by hand with a small mallet — two walls that enclosed the eat-in kitchen. He built bookcases; filled the walls with posters from the now long-gone Wittenborn art-book shop; and bought paper lanterns from Azuma, the beloved and also long-gone venue for Japanese paper lanterns and home accessories — as well as one small cubic lantern by Isamu Noguchi. He covered the concrete floor of the balcony with redwood duckboards from the lumberyard across the street (redwood was still legal at the time). But it was his decision to skew the furniture at a 45-degree angle within the south-facing living room that really opened up the space.

His apartment was featured in House & Garden’s Guide for Young Living in 1969. The black-and-white photographs by Louis Reens show it very much as it looks today. Over the years, as the books and collections of skulls, claws, and toy soldiers have accumulated, more shelves have been added, and he donated his underused harpsichord to the Berkeley Carroll School to make room for more storage.

The balcony was enclosed, adding more space for books. Today, a dramatic carved-oak throne in the shape of a skeleton resides near the unsigned portrait of Francesco Maria della Rovere, the fourth Duke of Urbino. (“I have a threevolume set of all six dukes of Urbino,” Alpern says, “so I know he was born in 1490. He died, probably poisoned, in 1538.”) The portrait “was in wretched condition. I had it relined, restretched, cleaned, repaired, and framed,” he says. “The only other known painting of him was done by Titian in 1538, the year he died. It hangs in the Uffizi.” If the skulls, claws, and the possibly poisoned duke all sound a bit macabre, it’s worth noting that Alpern had a notable collection of Edward Gorey drawings, books, and ephemera he donated to Columbia in 2010.

Was Alpern ever tempted to move? “When I bought the place from plans when I was 21, my intention was that it be my permanent home,” he says. “And knowing the Manhattan real-estate market, I knew that once I had my own place, it would be forever. We Alperns don’t move around a lot.” And that B. Altman sofa hasn’t moved from where he first put it, either.

More Great Rooms

- The Selby’s New Book About Creatives With Kids at Home

- ‘If I Had to Leave This Place, I Would Probably Leave New York’

- I’ll Never Forget the Apartment Gaetano Pesce Did for Ruth Shuman