This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In this article

Electchester technically comprises just 38 buildings — squat brick towers tucked neatly between the Long Island Expressway and NYCHA’s Pomonok Houses. But residents of the co-op complex know it’s really about what winds among the actual apartments: two shopping centers, a bowling alley, a public school, a library. A nearly century-old Jewish club that meets in an imposing office building with its original mid-century phone booths. The “rumpus rooms” in residential basements, where a Cub Scout pack gathers and children’s birthday parties are held. On any given night, a handful of clubs — the Motorcycle Club, the Electrical Welfare Club — might assemble. There’s no real need to ever leave Electchester except to commute into Manhattan for work, the same way it’s always been — a slice of 1950s middle-class utopia smack in the middle of Queens.

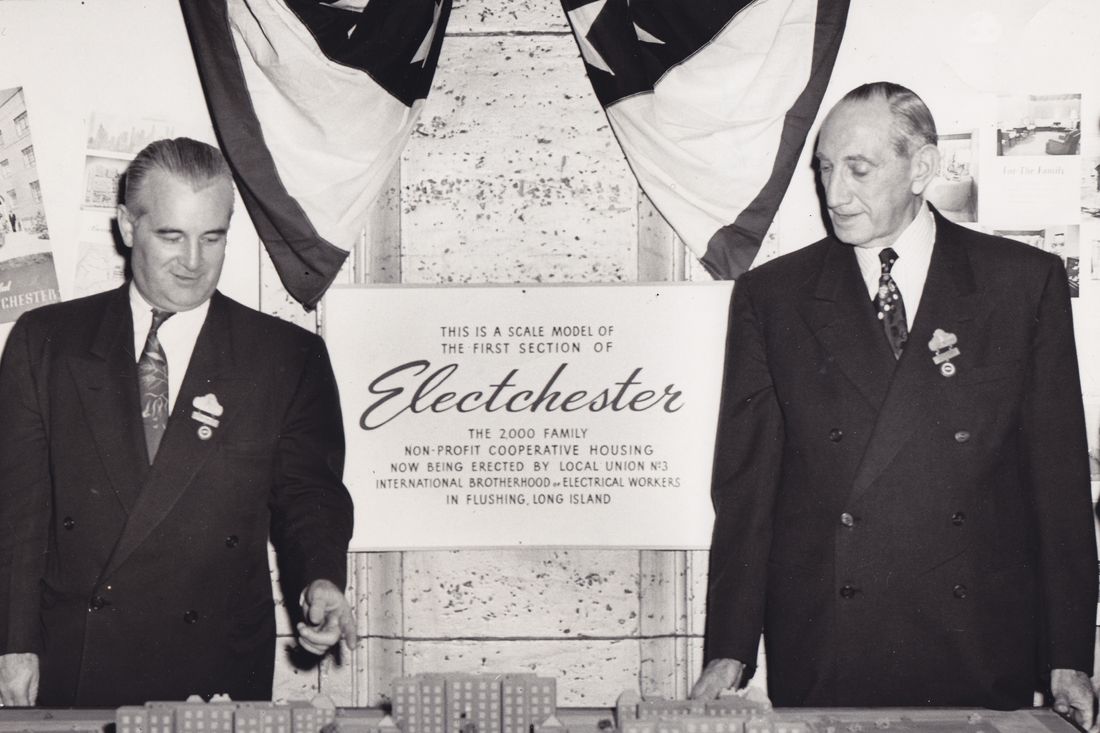

Electchester was established in 1949 for a very specific group of people: electricians. Or, more specifically, the members of Local No. 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. It wasn’t unusual at the time for unions to create affordable worker housing. The meat-cutters had an apartment complex in the Bronx, the ladies’-garment workers a co-op in Chelsea and on the Lower East Side. (Support for these began to die out in the 1970s amid the city’s financial crisis and a national retreat from subsidized housing — Electchester is the rare one that remains even close to its original iteration.) Local No. 3’s business manager at its founding, Harry Van Arsdale Jr., chose what had been a country club in eastern Queens to eventually become Electchester. He liked the area for its size — a 103-acre plot of land where thousands of laborers could grow their families in actually big-enough apartments. By 1953, a lucky batch of mostly working-class white second-generation New Yorkers had moved into this quasi-suburban development, a big step up from their overcrowded city apartments and public-housing projects. Apartments in the red-brick buildings were grouped into housing companies Nos. 1 through 4 and were scattered along Parsons Boulevard, 164th Street, and 65th and Jewel Avenues. They don’t appreciate in value the way traditional homes do — when residents leave, they simply get their down payments back (minus wear and tear). In the early days, those down payments began at $470, and the monthly carrying charges were at most $28.27 per room. (Those vary by apartment size, and sometimes income, and stayed especially cheap until the late ’90s, when the co-op lost state-tax abatements helping subsidize costs. Today, carrying charges remain well under market-price rent, and down payments range from $7,000 to $16,250.)

In the beginning, nearly all of Electchester’s apartments were filled by electricians and their families; residents say the union strongly influenced who moved in and who didn’t, though the union denies this. “It was like growing up in an old-school coal-mine town; if you grew up there, you worked in the coal mine,” says Andrew Fischer, 57, a retired electrician who’s lived in Electchester for most of his life. (There were a few relative outsiders — Max Weinstein, for instance, who moved in with his wife, Miriam, and sons, Harvey and Bob, worked as a diamond cutter.) The union and the co-op became even more intertwined in the ’60s, when Local No. 3 moved its official office building right onto the outskirts of the co-op. Downstairs was a new bowling alley, JIB Lanes, named after the organization of electrical-union workers and contractors and christened by professional bowler Dick Weber. When, later that decade, “the Towers” opened — a more luxe set of buildings with picture windows, private terraces, and, in some apartments, multiple bathrooms per unit — it filled up quickly with union executives, among others.

The People Who Live There

Inside four apartments.

RESIDENT SINCE 1954

Charlie Fahlikman

Former local union president for the Social Security Administration

We moved in when I was 4 and a half years old from Crown Heights. My father was in Local No. 3; he worked for Leviton, which made all kinds of electrical switches. In 1977, I got my own apartment in the complex — 50 feet away from my parents. I paid $139.10 for a two-bedroom. Now it’s $1,250. I met my wife in the building. One of my childhood friends was just back from Vietnam, and he came to see if I wanted to play tennis in Cunningham Park with his girlfriend, Pat, and her friend. I’ve been married to the friend for 50 years. For our anniversary, we went to Valentino’s on Kissena Boulevard. The owner there calls me “Mr. Electchester.”

RESIDENT SINCE: 1991

Marcel Johnson

Gym teacher at Forest Hills High School

I grew up in First Housing in a two-bedroom apartment. The courtyard was downstairs, and it had great grass; Electchester is known for its great grass. I had the best and deepest relationships of my life in that building. Like the Gills — they’re this popular family in Electchester because Curtis Gill Sr. grew up here and raised his family here. We were like one family. My father cooked dinners for them; Curtis Gill Sr. cooked dinner for us. Curtis Jr. just moved down the block to Fourth Housing, and he’s still one of my closest friends. Like a brother. These days, he’ll come over with his girlfriend, and I’ll bring my girlfriend — social get-togethers that just happen to be in the exact same building we grew up in.

RESIDENT SINCE 1987

Tommy Prezioso

General manager at Electchester Management LLC

In ’87, I was working as an apprentice to an elevator mechanic. And he recommended I write a letter to Jerry Meyers, the director for First Housing, to see if I could get a place. I dropped it off at the union hall, and two months later he invited me in for an interview. It was a marvelous place to raise children. Especially during the holidays. Everybody had their doors open. I would take a milk can to prop mine open and cook my own food — sausage-and-pepper heroes, lasagna, sausage, meatballs — for hours and hours, and anybody who came down the steps and smelled it would come in. We still have a pretty great Christmas celebration. There’s a big tree lighting; I run electric with all the volunteers, set up the stage, prepare the grounds. Some of the cooperators and presidents make a 12-foot-long menorah with actual lights that work. And elevator mechanics volunteer their time to DJ.

RESIDENT SINCE: 1973

Helene Beides

Retired dental-office manager

When I met my husband in 1968, he was living in Electchester and so was his whole family. His aunts, his uncles, his cousins. Once we got married, I moved in too. It was very, very social. The women ran card parties. We’d sell tickets, and some Friday nights, you’d come down to the rec room and play mah-jongg, dominoes. I’m on the board of my housing company now — it’s 11 men and me. We vote on issues and discuss what’s going on, repairs. Everybody is a resident and, except for me, a union member. I’m the token lady; I bake and bring goodies. I really enjoy it.

Electchester Extracurriculars

There’s an Extremely Active Cub Scouts Pack

In 2018, Electchester Cub Pack 357, which has met in the basement of Second Housing since the 1950s, was on the verge of closing. Once counting 30 Cub Scouts (enough that at one point the pack had to split into two dens), it had dwindled to three — two short of the minimum required by Boy Scouts of America, according to Richard Mroz, a Local No. 3 electrician and Electchester resident who assumed the position of Cub master that same year. “It was just my two boys and one other kid,” Mroz says. So he went into high gear with recruitment. “Me and my boys would get dressed up in uniform and stand out in front of P.S. 200 and hand out flyers.” Between the flyering and an especially lucrative lemonade stand at the Electchester street fair (the funds from which Mroz used to buy a pinball machine and pool table for the Cub Scouts meeting room), membership increased rapidly. By 2019, the pack had grown to 14. Every Friday night, the group assembles in its basement meeting room, which Mroz repainted Cub Scout blue and yellow. They craft small wooden cars for the district’s Pinewood Derby (Cubs have been awarded Most Patriotic and Best Monster Cars in recent years) or practice leading the Pledge of Allegiance for an upcoming event like the co-op’s tree-lighting ceremony.

And a Very Well-Used Bowling Alley

JIB Lanes was overhauled in the summer of 2008 — the owners swapped out aging wooden lanes for synthetic ones and replaced the analog scoring system. But it still functions much as it did in the ’50s, according to general manager Marlon Enriquez. “The electricians-union bowling league still meets here on Monday nights,” he says. “Everyone calls each other brother.”

On the Second Thursday of Every Month, Hundreds of Electricians Gather in the Auditorium

These membership meetings are meant to follow conventions spelled out in the union constitution (financial updates, business reports, death notices) but have gotten a bit rowdy in the past. In the early 1930s, meetings tended to dissolve into brawls as members clashed over who should lead the local. Van Arsdale was once convicted of assaulting two members during a particularly violent meeting in 1933 (though it was reversed on appeal). According to Christopher Erikson, 67, the current business manager of Local No. 3 (and Van Arsdale’s grandson), they’re generally a bit calmer these days. “Anybody can comment on anything at any time; there are microphones on the floor, so when my report is done, they can say what they have to say. But when you’ve got 1,000 guys in a room, you don’t want to hear a guy get up and talk about how he had a bad day. By the time the meeting is over, most guys have heard what they needed to hear, and they go home,” he says.

The Place Inspired a Play

In 2018, the Working Theater at Urban Stages debuted playwright Adam Kraar’s Alternating Currents, based on Electchester. Soon, he says, the company plans to bring the performance back to the union hall for residents. Here, an excerpt.

LUKE: Babe, it’s for electricians.

ELENA: Really? You mean that whole complex with the lawns and the—

LUKE: Harry Van Arsdale Jr.?

ELENA: I know who Harry Van Arsdale is—

LUKE: (moving to her) Electchester was like his brainchild. He got it built back in the ’50s, so people from Local No. 3 could have affordable homes. We should apply.

ELENA: We’re gonna buy an apartment? Is this before or after you pay off your Expedition EL with the heated seats?

LUKE: The down payment for a place over there? Not that much — we’re not apprentices anymore; we’re making union scale. And the monthly maintenance for a one-bedroom? Less than half what we’d spend anywhere else. For what we’re paying now and what do we get? I love you, babe, but this place is so small it gives “up close and personal” a bad name.

JERRY: (to audience) The buildings at Electchester — 38 in all, over a hundred acres — are not remarkable. They have problems like any building would after more than a half a century. But then you meet the people.

How to Get an Apartment Here

Send a letter to 65-46 160th Street, Flushing, New York, 11365 requesting an application. Electchester management denies it, but some residents think Local No. 3 affiliates are still better off in the housing process, so definitely include mention of any union ties in your letter and application. “It’s my impression that those Local No. 3 connections live on a little,” says Andrew Fischer, who, in the late ’90s, got an apartment in a few months despite what he remembers as something like a one-to-two-year waiting list at the time. If you don’t have any connections to the union, residents recommend including a sob story. Levy, who grew up at the co-op but isn’t a union member, says she wrote several “tear-jerking letters” about her divorce and got an apartment within three years (less than the wait time for many, which management says can stretch up to ten years). Before receiving an offer, expect to come in for an interview, and be ready to show you can pay the monthly charges and the down payment in full immediately — with such high demand, the turnaround time for moving in is usually a few weeks.

But Good Luck Finding a Parking Spot

The issue of parking brings out “high emotions” in most residents, says Neal Siegel, 53, a Local No. 3 electrician and former resident who says he’s seen people leave nasty notes on cars parked in their spots and call tow-truck companies on neighbors. One woman says the union had her father’s parking spot taken away for a time as punishment when her baby made too much noise in the apartment above the family of a union executive. (The union denies taking parking away from residents — or having any influence over it.) Now neighbors routinely park a ten-minute walk away from their apartments and the wait for an outdoor spot is yearslong. “There are garages, but you’re not going to get a spot in there. Forget about that,” says Burka, who has been on the list for an outdoor spot for more than a year. To make matters more complicated, the boards are now dealing with electric-vehicle parking — an issue that’s become ironically challenging for Electchester, since many garages don’t currently have electricity (a holdover from the co-op’s early days that was meant to discourage residents from making a mess while tinkering with their cars). “An electrical union owns the space,” says Siegel, “so you’d think they want to promote electrical-vehicle charging.”

After Electchester, It’s Florida

A lot of former Electchester residents have since moved to the state — not an entirely uncommon situation for New York retirees. But there are so many that they find themselves running into one another. “A childhood friend of mine just bought a place in a development down the road,” says Ronni Manela, 67, who was born and raised in Electchester and brought her children up at the co-op before moving to Florida four years ago. “We’re going to get together soon. I haven’t seen her in over 40 years.” One entire Electchester friend group that moved in with the first wave of residents decamped en masse to Hawaiian Gardens in Fort Lauderdale.

More From This Series

- A Duplex is For Sale in the Coveted Villa Charlotte Brontë

- Inside Olympic Tower, Where Foreign Billionaires Have Long Flocked

- What It Was Like at Twin Parks North West Before the Fire