Even if an idea does not strictly start here, New York is, disproportionately often, the place where it is dropped off, trimmed to size, matted and framed, and displayed to everyone with an explanatory wall text.

Certain types of people are drawn to a place like this. They tend to be young, smart, and ambitious. Definitionally, they are dissatisfied with their hometowns. (Otherwise, why leave?) Home to authors and academics and musicians, art galleries and fashion houses — how exactly did this majestic confluence of creativity appear here? One explanation is New York’s sheer size: Big ideas are magnetic, and in a big town rather than a small one, you can gather enough Trotskyites or avant-garde poets at an event to make waves. There’s a self-fulfillingness to these things too: Self-confidence begets self-confidence, and centrality draws people who want to be at the center, which makes the center bigger. Not to mention the fierce competition.

It is, of course, not a place for everyone. People come here to try to shoot the moon. If it doesn’t work out, a lot of them go back to where they came from, or sometimes to New Jersey. Those who hang on are a self-selected subset, intent on making something never before seen. You can hardly go a day without encountering something that started here. The list is, you might say, encyclopedic. And, in fact, the entries that follow have been adapted from the forthcoming Encyclopedia of New York, a book compiled by the editors of this very magazine. It’s a history of New York’s core power — innovation — and of the ways in which one city exports the intentions, whether corporeal or intangible, that have shaped our everyday existence for hundreds of years. It was always a terrible, great idea to move here and shoot your shot, and it still is. The apartment next door to you may be cramped, but the ideas that will define everyone’s life a few years hence may lie within.

A

Abstract Expressionism

Acrylic Paint

ACT UP ▾

By 1987, the AIDS epidemic had claimed almost half a million lives worldwide and over 6,500 in New York City. Early that year, the playwright Larry Kramer spoke at the LGBTQ Community Center on West 13th Street and told a roomful of primarily gay men that two-thirds of them would be dead in a few years if they did not take radical steps. Two nights later, about two dozen people met at Kramer’s Greenwich Village apartment and launched the activist collective ACT UP (for AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which went on to score some of the biggest gains against the epidemic before an effective treatment emerged in 1996. With its unapologetically queer rhetoric and aesthetic — the signature chant was “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” — ACT UP effectively defined what it meant to be LGBTQ and political in the U.S.

Air Conditioning

Algonquin Round Table

Alt-Weekly

Amazon.com

Anchorman

Anthora Cup

Atomic Bomb

Auteur Theory

Automat

Automated Teller Machine

B

Bagel

Barbicide ▾

As a teenager, Maurice King was disgusted that barbers simply used water to clean their combs. In 1947, after earning a degree in chemical engineering, he started mixing batches of chemical disinfectant in the bathroom of his Brooklyn apartment. He dyed it electric blue to signal purity, leaving a permanent stain on his bathtub. He then began lobbying for a law requiring the use of disinfectants in barbershops. The states bit, and many wrote legislation requiring the product by its name, Barbicide — which, King joked, means “Kill the barber,” a nod to his teenage distaste.

Baseball

The Beats

Bebop

Bike Lane

Birth-Control Clinic

Bloomberg Terminal ▾

Bodega

Brassiere

In 1913, Mary Phelps Jacob, a 21-year-old New York debutante, was dressing for a dance. Repeatedly frustrated with the corset that was, at the time, the literal foundation of a well-dressed woman’s attire, Jacob asked her maid to bring her two silk handkerchiefs, a ribbon, and a needle and thread. The garment she assembled, she later said, “was delicious. I could move more freely, a nearly naked feeling, and in the glass I saw that I was flat and proper.” Although a variety of similar garments predate her patent, she is generally credited with the invention of the bra.

After her underwear breakthrough, she moved to Paris for a while; co-founded the Black Sun Press, publishing Ernest Hemingway; married three times; changed her name to Caresse Crosby; worked as an antiwar activist; dabbled with opium-smoking in North Africa; owned a dog named Clytoris; and died in 1970 at the age of 78, not far from the castle she owned in Rome.

Break-dancing

Brill Building

Broadway

Brownstone Rowhouse

C

Café Society

Cel-Ray Soda

Chabad Judaism

Chemex Coffeepot

Christian Realism

Christmas Lights

Club Kids

Club Sandwich

College Entrance Exam

Cooperative Apartment Building

Crayon

Credit Reporting Agency

Cronut ▾

The Cronut, a cross between a filled doughnut and a croissant, invented by French-born pastry chef Dominique Ansel, made its debut at his Soho bakery on May 10, 2013, heralded by Hugh Merwin on New York’s Grub Street blog as a “Hybrid That May Very Well Change Your Life.” The tourists are still lining up for it.

Crossword

D

Department-Store Holiday Window Display

Deuterium

Digital Ad Exchange

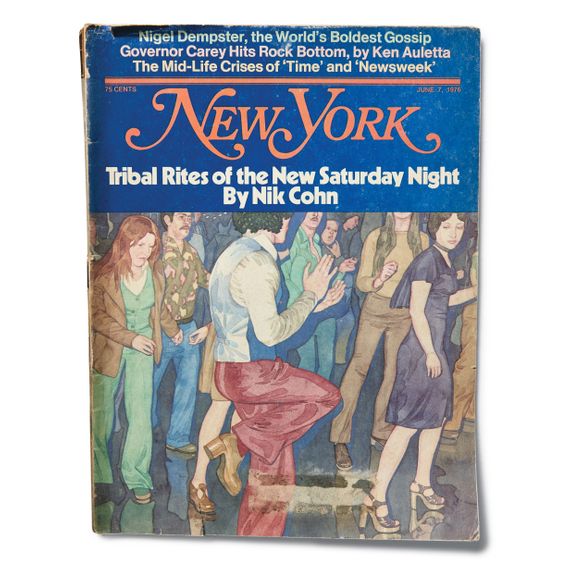

Disco ▾

Discount Store

Dollar Slice

Double Dutch

Dow Jones Industrial Average

Downtown

Dry Cleaning ▾

“Letters patent being granted under the Great Seal of the United States of America unto Thomas L. Jennings, Tailor, 64 Nassau Street, New York” — thus ran a line in the New York Post on March 27, 1821, marking the first U.S. patent issued to an African American for Jennings’s system of “Dry Scouring Clothes, and Woollen Fabrics in general, so that they keep their original shape.” We’d call it “dry cleaning” today, and the advertisement says the technique “also removes stains from cloth.” Jennings was a free man, but his wife, born in slavery, was an indentured servant; he made enough money off his invention to buy her freedom.

E

Easter Parade

Egg Cream

Eggs Benedict

Electrical Grid

Elevator/Escalator

Ex-Lax ▾

A year or so after he graduated from Columbia University’s pharmacy program in 1904, Max Kiss fell into a conversation with a doctor who mentioned Bayer’s new drug phenolphthalein, which relieved constipation. Mindful of children who resisted swallowing their repulsive spoonfuls of castor oil, he embedded the phenolphthalein in chocolate and introduced his product in 1906. He named his product Ex-Lax for a Latinate phrase he’d picked up in Hungary that describes political deadlock: Ex-lex is a condition under which the Constitution is temporarily suspended and Parliament is dissolved, during which no legislation can, uh, move.

F

Façade Law

Federalism

Federal Reserve System

Flashmob

FM

Freak Show

Free Verse

G

Game Show

Gay-Rights Movement

General Tso’s Chicken

Gentrification

Gin Rummy

Gossip Column

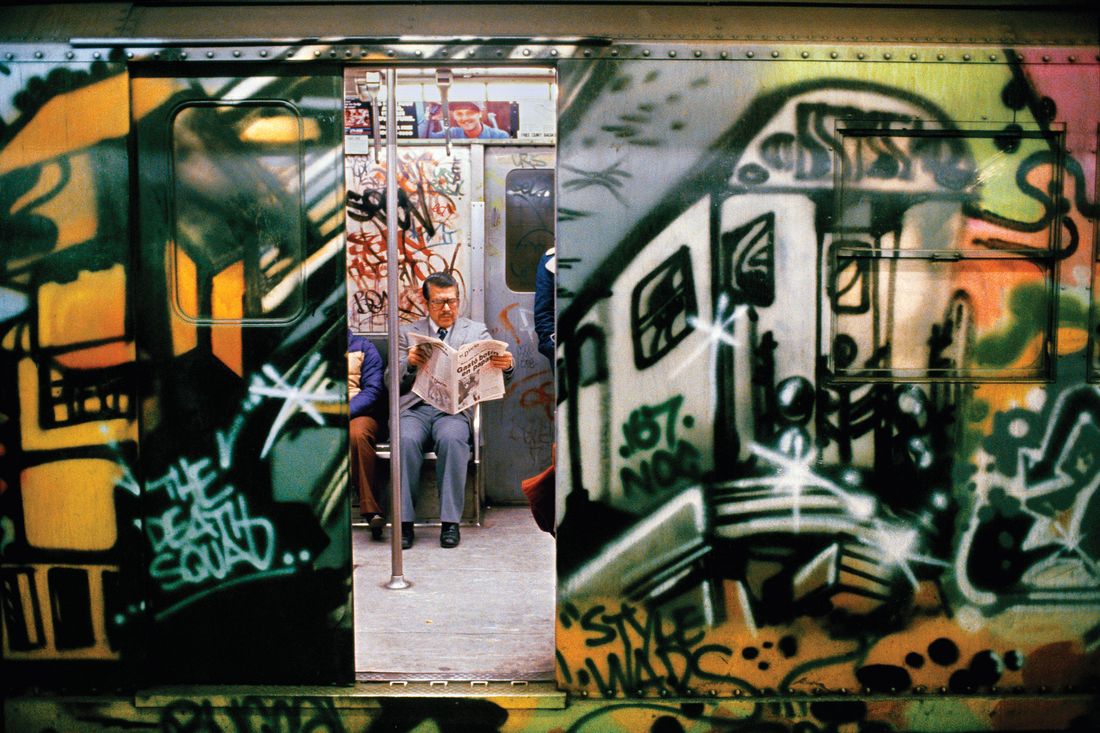

Graffiti As Art

Gum

H

Halal Cart

Hare Krishna

Halligan Bar ▾

Virtually every fire department in the U.S. buys its men and women the same tool: a steel bar a couple of feet long with a forked chisel at one end and an adz and spike at the other. It’s called a Halligan bar, and it can pop open a door, break a window and clear the frame of glass shards, bash through a Sheetrock wall, and provide the leverage to open a stiff water valve. The FDNY chief Hugh Halligan designed and patented it in 1948, improving on a cruder predecessor known as a Kelly tool (invented a generation earlier by another New York fire captain, in fact).

Hall of Fame

Harlem Shake

Hedge Fund

Highway, Elevated

Hip-Hop ▾

Cities are a lot like bodies. Proper circulation keeps cities alive; cut off access, and rot sets in. Robert Moses — the famed “master builder” of New York City and, by extension, the whole urban United States — frequently decimated neighborhoods and shoveled families into public housing that displaced Latino and African American residents with surgical precision. And hip-hop is the child of the disorder that Moses visited on communities of color. In those decaying neighborhoods, Bronx youths created their own infrastructure and then their own culture.

In the summer of 1973, the Jamaican-born Bronx kid Clive Campbell, a.k.a. DJ Kool Herc, cleverly crossed Kingston dancehall and soundsystem culture with thriving American funk music. Herc, while DJing his sister’s birthday party, decided to show off a trick he’d been practicing. Instead of playing songs all the way through, he cued up two copies of the same record, zeroing in on the dance break and using two turntables to run it back on a continuous loop. He was looking for the perfect beat, whittling leaner, tighter dance-floor routines out of hit records. Herc’s isolation of the white-hot instrumental sections of James Brown and Incredible Bongo Band records is the backbone of the sound of rap music. The practice made maestros out of children who couldn’t afford instruments and/or a musical education. The music made party planners out of anyone who could jack enough juice to power turntables, microphones, and speakers.

Hipster

Home Security System

I

Illuminated Advertising Sign

Immigration

Incubator

Iron, Electric ▾

“Ivy League”

J

Jaywalking

Jazz

Jeans, Designer ▾

The workingman’s denim pants, invented in 1873 by Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss, varied little for a century until Gloria Vanderbilt — designer and heiress to one of America’s great fortunes — was approached in 1976 by the Indian garment manufacturer Murjani. The jeans they came up with walked a line between sexy and accessible. Made of stretch denim, they “fit like the skin on a grape!” as one TV ad promised. But they were also comfortable and wearable for the average woman. Vanderbilt starred in the print and media ads and grossed $30 million in sales in the first year. As Gilda Radner put it, Vanderbilt took “her good family name and put it on the asses of America.”

Jell-O

Junk Bonds

K

Key-Lime Pie

Klieg Light

Knickerbocker

L

Labor Law

Lap Dance ▾

In 1973, Al Kronish, an enterprising accountant, convinced Fred Cincotti, an assistant D.A. for the State of New York, and Steven Katz, heir to a construction empire, to invest in a brand-new strip club in Times Square. The Melody Burlesk was supposed to be classier than the other dives in the area, and it bombed. To save the club, they started hiring porn stars to put on shows there. In 1978, the club introduced Mardi Gras, a raucous weekend event where, for the first time, strippers interacted directly with the audience, grinding on their laps for just $1 per sitting. Word spread, men began lining up to get one of these newfangled “lap dances,” and things devolved from there.

Late-Night Talk Show

Leotard As Streetwear

Lindy Hop

Loft Living ▾

M

Magic Marker

Manhattan

Mayhem

Mr. Potato Head

The Mob

Mortgage-Backed Securities

Muckraking

Musical Theater

N

NRA

Neoconservatism

News Blog

Nightclub

O

Occupy Movement

Oreo

P

Parking, Alternate Side of the Street ▾

The New York City Department of Traffic was established in June 1950 as the postwar auto boom threatened to swamp New York City with cars. Within weeks of its creation, the DOT was beseeched by the city’s Sanitation commissioner, Andrew W. Mulrain, to try out a new plan on the Lower East Side: a scheme to ban parking on each side of the street on alternating days, allowing the DOS to clean at the curbs. Fifteen hundred signs went up that July, and the law took effect on August 1. The local auto clubs howled, but by the end of the year, the arrangement had been expanded to the Upper West Side and over the next few months into Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Within two years, the city was declaring the plan a success because of the substantial parking-fine revenue and (according to Mulrain) cleaner streets.

Pastrami Sandwich

Penthouse

Period Underpants

Pickleback

Pilates

Pooper-Scooper Law

Pop Art

Power Lunch

Public Defender ▾

On March 8, 1876, a group of German-Americans met on Wall Street with the lawyer and former Wisconsin governor Edward Salomon, aiming to form an organization that would provide legal assistance to German immigrants who could not afford a private attorney. Out of that group, the German Legal Aid Society was born with the purpose of defending immigrants from, as its chief attorney, Leonard McGee, put it, “unscrupulous people, who, on one pretext or another, would manage to rob them of the little they possessed.”

The Society handled 212 cases in its first year; in its fifth, it took on 2,832. In 1890, the group began offering assistance to non-Germans who “appear worthy and at the same time [are] unable to pay.” The organization changed its name to the Legal Aid Society on June 1, 1896. Today, there is a similar society, if not more than one, in every state.

Public Relations

Puffer Coat

Punk

Q

Q-tips

Quant

R

Rabbit Ears ▾

Radio Broadcasting

Remote Control

Romantic Comedy ▾

The first onscreen kiss — 50 feet of celluloid, running about 20 seconds — was shown in New York in 1896. Appropriately titled The Kiss, it was among the first motion pictures ever shown theatrically to a paying public, produced by Thomas Edison and starring May Irwin and John Rice. (It also caused a brief uproar over the depiction of such wanton sexuality.) On film, the comedy-romance — an ancient theatrical form — developed organically through situational and romantic vignettes produced by such New York studios as Vitagraph, Mutoscope (later Biograph), and Independent Moving Pictures. But oddly enough, the city emerged as a popular setting only after the industry began its move west. Cecil B. DeMille, a New Yorker who had decamped for California (he directed Hollywood’s first feature film), re-created New York locations in Los Angeles for 1914’s What’s His Name and 1915’s Chimmie Fadden. DeMille would go on to make a series of successful remarriage comedies, including 1919’s Don’t Change Your Husband and 1920’s Why Change Your Wife?, both starring Gloria Swanson. It’s a fairly straight line from there to Meg Ryan in the deli in When Harry Met Sally …. Read more on Vulture.

Rush Tickets

S

Safety Pin

Scrabble

Singles Bar

Sitcom ▾

In November 1947, the DuMont television network aired the fifteen-minute premiere of a show called Mary Kay and Johnny. It was the first American television sitcom, appearing several months before the first officially programmed season of network television, and it was unlike anything viewers had seen before. Most early experimental shows were either adaptations of radio programming, coverage of sporting events, variety shows, or stand-alone fictional stories like those on Kraft Television Theatre. But Mary Kay and Johnny returned every night to the same two characters (played by real-life couple Mary Kay and Johnny Stearns) in the same tiny New York apartment. It was an ongoing comedy about an American family at home and featured short, funny stories about domestic life and minor marital squabbles. In the show’s one surviving episode, Johnny chides Mary Kay for buying a small brush from a door-to-door salesman, only to get suckered into buying a much more expensive vacuum when the salesman returns. Read more on Vulture.

Sketch Comedy

Socialite

Steamboat

Subway Series

Supermarket

Suspension Bridge

T

Tabloid Newspaper

Ticker

Toilet Paper

Tootsie Roll

Traffic Regulations

Tuxedo

U

Unions

United Nations

Urinal

V

Vaudeville

Vermont

Voguing

W

Waldorf Salad

“Walk” Sign

Wine List

Wrap Dress

Wrecking Ball ▾

Instead of succeeding his deli-owner father, Sussman Volk — inventor of the pastrami sandwich — in the construction of edible high-rises, Jacob Volk went into high-rise destruction, becoming New York’s foremost expert in the demolition of tall buildings. In his early days in the business, these structures were painstakingly taken down by hand, mostly by men with crowbars. But in the 1930s, Jacob and his brother Albert began knocking down walls and columns with a hanging slab of scrap iron suspended from a crane. By 1936 the Volks were using a 3,000-pound “iron cannonball” swung from a 90-foot-tall arm.

As the low-rise 19th-century city gave way to the high-rise 20th, the wrecking ball became ubiquitous. In recent decades, its use has begun to fade: Although it hasn’t vanished from the demolition trade altogether, for big buildings implosion is faster and more efficient. It’s used today less as a physical tool than as a convenient metaphor, most notably by Miley Cyrus, whose 2013 single “Wrecking Ball” was accompanied by a video of her riding one as it swung from a chain. A smash hit.

X

Xerography

Y

Yellow Journalism

Yuppie

Z

Zipless Fuck

Zoning ▾

When yet another super-tall tower pokes past the Empire State Building, New Yorkers routinely ask, “Who let them build that?” The answer often involves zoning, a rulemaking art that goes back to New Amsterdam, when Peter Stuyvesant issued a code limiting the number of taverns, designating certain areas off-limits to pigs and goats, and preventing shacks and fences from spilling over onto public streets.

Modern zoning, however, was precipitated by one particular event: When the 40-story Equitable Building went up in 1913, eating up a whole block and looming over lower Manhattan’s old, narrow streets, New Yorkers clamored for more regulation. Two well-connected reformers, George McAneny and Edward Bassett, wrote the nation’s first zoning resolution, a revolutionary document enacted in 1916 that shaped growth for decades.

The regulations can get detailed and arcane, but they express the way each place and period sees the challenges of living in close proximity; the political cost of trying to change that is formidable. Today it’s often the urban frontier where battles over gentrification, equality, and justice are waged and the future of the city is defined.

From The Encyclopedia of New York, by the Editors of New York Magazine. Copyright © 2020 by Vox Media, LLC. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

*This article appears in the October 12, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!