The hell of it was, the kidnappers had taken the wrong brother.

Arthur Fried was a 32-year-old sand-and-gravel-company manager living with his wife and son in White Plains. On December 4, 1937, he’d gone to his mother’s for Saturday-night family dinner, and then to a movie with Elsa and Harold Daniels, his sister and brother-in-law. When the show ended, with a snack at the Daniels’ place planned, Arthur asked to be driven back to his mother’s house. saying “I’ll get in my own car and follow you.”

He never made it. Witnesses saw a man force Fried’s car off the road and take him at gunpoint. In the middle of the night, the phone rang at the Daniels’ home: “Don’t worry about Arthur. He’s had too much to drink, but he’ll be all right. You’ll hear from him in a day or so.”

That set off all of the alarm bells: Arthur didn’t drink. Gertrude, his wife, insisted on speaking to him. The caller refused. “If I don’t call back in 15 minutes, I’ll call you later in the day.” A note demanding $200,000 in ransom soon appeared, followed by dozens more phone calls asking for varying (and declining) dollar amounts. But there was no sign of Arthur. Six weeks in, his family gave him up for dead.

That changed in July 1938, when 19-year-old Norman Miller, home for the summer from Franklin & Marshall College, caught a movie with a friend in South Brooklyn. By the time they realized they weren’t alone on the drive back from Quentin Road and Coney Island Avenue, and that two men had pounced upon the running boards on either side of the car, it was too late.

Miller, however, was coolheaded enough to notice and retain as many details as he could. “A Tisket, A Tasket” on the radio as the kidnappers crossed the bridge into Manhattan. Going up steps to the room where he was held overnight. Church bells clanging outside. The distinctive sound of cues hitting balls on a pool table.

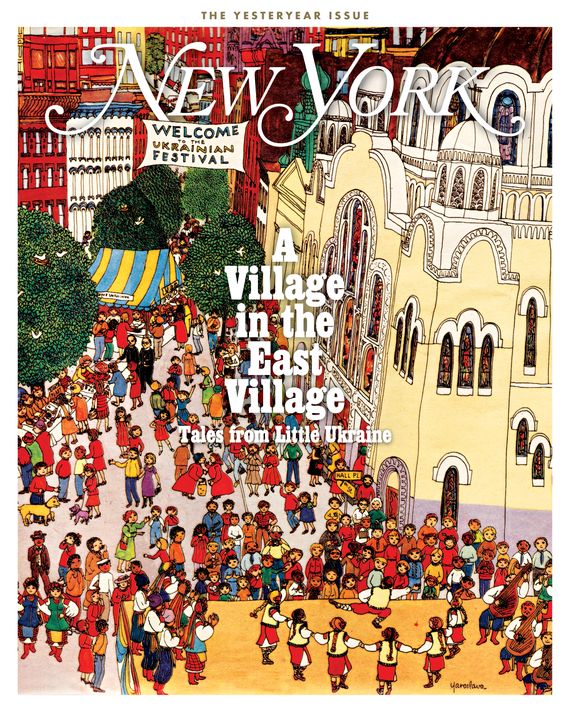

Miller would be released on a $13,000 ransom the following evening. With those details – and the fact that Miller’s father, Charles, apparently knew one of the kidnappers – the FBI traced things to Ukrainian Hall, a meeting space and settlement house at 217 East 6th Street. It was operated by Denis Gula, an immigrant with rumored ties to fascistic groups. One of the four kidnappers turned out to be his son, Demetrius. All of them—Gula, Joseph Sacoda, John Virga, and William Jacknis—had served various stints at Sing Sing prison throughout the 1930s. (Jacknis was the kidnapper who’d been acquainted with Norman Miller’s father, Charles, described this way decades later by someone claiming to be his grandson: “Let’s say that he was a fruit importer in the same way that Tony Soprano was in “waste management!”)

As they confessed – almost certainly through coercion and beatings, not that it mattered, certainly not to the jury who would convict them of various offenses – the quartet admitted involvement in several other robberies not previously reported to police.

In the process, the feds finally learned what happened to poor Arthur Fried. Sacoda had served time with Fried’s older brother, Hugo, the original kidnapping target. A misreading of license plates led to the accidental sibling swap. Sacoda and Gula had stashed Arthur in an apartment on 19th Street, near Gramercy Park. Four days later, when the news hit the papers, Sacoda shot him. He and Gula took Fried’s body to Ukrainian Hall, where they burned it in the furnace.

The FBI would raid the place on November 2. The Daily News first reported that police found “at least twenty bones” as well as “a cleverly-hidden 10x10 execution chamber, the walls of which were pock-marked with bullet holes.” Only later did the coroner’s office reveal that the bones were not human, and that the killing had happened elsewhere. None of it was enough to make murder charges stick—but thanks to a six-year-old “Lindbergh law” in New York State, if a kidnapping victim couldn’t be found alive at the time of trial, he was presumed to be dead. And if the jury convicted and made no recommendation for mercy, Sacoda and Gula faced a mandatory death sentence.

On January 27, 1939, Sacoda and Gula were the first to be sentenced to die for a crime other than murder. Both were executed almost a year later, on January 11, 1940. Gula, smirking, went first. He reportedly leaned over to an official, muttered a wisecrack, and the grin remained as the black mask went over his face and he was strapped into the chair.

Ukrainian Hall outlasted the two of them, but not for long. According to the New York Post, business at the bar was ruined by the notoriety. During the trial, the building’s restaurant operator, the senior Gula, lost his liquor license for violations nominally unconnected to the kidnapping. The building itself is no more: It was torn down in the 1950s, and the church school on 6th Street now occupies its site. The Ukrainian National Home, around the corner, fills an array of its non-murder-related community functions.