Master builder and installation artist Randy Polumbo wasn’t exactly looking for a lighthouse, or at least that’s the way he tells it. “I was on a government website late at night looking for decommissioned fuel tanks,” he says. “I was going to make a weird garden out of those tanks. And I clicked on a large cylindrical item for $5,000 and it was the lighthouse.” For most people, none of that makes all that much sense. But for Polumbo, it was the perfect next challenge.

He has never liked the easy or the obvious. His office is in a five-ton vintage Dodge Travco camper that is hoisted in the air inside his 4,000-square-foot Gowanus studio. (It just wouldn’t have been as fun if it had been left on the floor.) So the fact that six years ago he had to pay a sizable sum to get on the bid list for the lighthouse (“They wanted to weed out the tire-kickers”) didn’t give him much pause. And when Polumbo saw it in person, he knew this was a prize that needed to be saved. “It had peeling lead paint, cauliflowers coming out of the plaster, rust, mold, mildew, and a few dead birds and some bird crap, but it definitely was beautiful in that kind of decayed, weird way,” he says. “It was a legit hazmat situation, but it was gorgeous.”

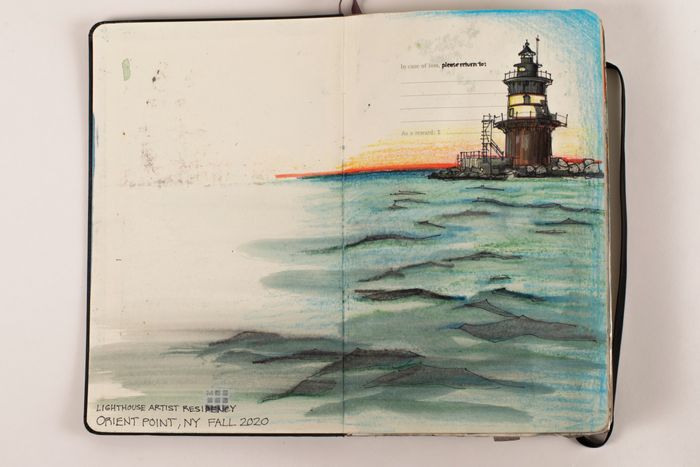

The lighthouse was built in 1899 on a rock pile, and the government no longer finds it cost effective to maintain such archaic structures. In any case, it was put up for sale. It’s hard to even get to. There’s only one way to reach the lighthouse, and that is to enlist Captain Bob Rocchetta to ferry you in his fishing boat from Orient. The approach is perilous, to put it mildly: His boat has to find its way through a narrow slip of jagged rocks to get near enough to dock; there’s no proper mooring, just a spit of concrete on the rocks with a metal ladder to scramble up. Once you’ve survived that, there are yet more rungs to climb to get into the lighthouse.

“I liked that it was doomed, and I felt that I could breathe new life into it, partly with other artists and creatives,” he says. “It had this incredible energy.” Polumbo hasn’t just salvaged the structure; he has made it into an art installation complete with electricity provided by solar energy, a composting toilet, and a silver-hued grotto above the level of the kitchen and sleeping area. “Cleaning it up wasn’t really the hard part. It took a lot of time figuring out the solar; I did different solar systems. I had two wind turbines that perished because the elements are so harsh — they literally blew apart. The one now is supposed to be a little more impervious.”

That settled, he turned it into an artists’ residency. To date, four artists have spent time there working on projects. Erin Currier was the first. She stayed for two weeks without leaving, save for a fishing trip with Captain Bob. “That was very exciting,” Currier says.

“I caught two striped bass at once on one line.” Currier saw a beluga whale one moonlit night, and the next night she saw a pair of them. “The whole experience was magical, and to stay in this living, breathing work of art of Randy’s was an honor.” The only thing she found daunting was not being able to take her two daily long walks. “So I ended up walking around and around the balcony a hundred times.”

If you want to get a lighthouse yourself, Polumbo has one piece of advice: “Make sure you get one with a real island,” not a pile of rocks. “Because then, typically, you own some land and you can have a water tank; you could even have a couple of goats and some chickens. It makes the whole sustainability thing easier.”

More Great Rooms

- The Selby’s New Book About Creatives With Kids at Home

- ‘If I Had to Leave This Place, I Would Probably Leave New York’

- I’ll Never Forget the Apartment Gaetano Pesce Did for Ruth Shuman