This story was originally published by Curbed before it joined New York Magazine. You can visit the Curbed archive at archive.curbed.com to read all stories published before October 2020.

The story of how Paul Savidge and Dan Macey became the owners of Louis Kahn’s Esherick House in Philadelphia started decades before the couple even met.

“I knew of the house as a young child because my parents were interested in modern architecture,” recalls Savidge. “I distinctly remember looking at the Esherick House while riding in the car, when I was 9 or 10 years old.”

When Savidge returned to the Chestnut Hill neighborhood as an adult in 2014, he had Macey by his side and the keys to the house in his hand.

“Sometimes, we forget it’s our house,” says Macey. “We’re amazed every morning when we wake up, and find the light different every time. We pinch ourselves that we get to live here.”

The Esherick House is one of a handful of homes in the Philadelphia region that Kahn designed during his prolific career. But of those nine homes, the Esherick House is arguably the most recognizable and iconic.

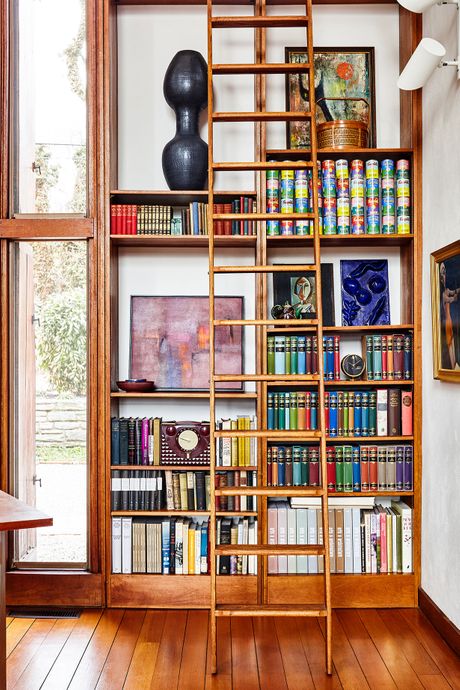

Kahn was a close friend of renowned sculptor Wharton Esherick, whose niece Margaret Esherick was in need of a house of her own, preferably one that could store all of her books. In 1959, Kahn agreed to design a boxy, two-story, one-bedroom house for the single woman, with her uncle taking the lead on the kitchen. Margaret was so eager to have her own place, she moved in before the home was even finished. Yet tragically, she died unexpectedly after living there for just six months.

Another family lived in the Esherick House for many years, until in 2008 it was put up for auction. Despite its claim to fame, the home languished on the market for years. A one-bedroom home is a tough sell, even with a pedigree. Over time, the asking price dropped little by little, with no bite.

Finally, half out of curiosity, Savidge and Macey decided to take a look.

“We went to see the house, walked out, looked at each other and said, ‘We can do this,’” recalls Savidge. “This would be really perfect for us, and we could be really good stewards of it — it could change our lives.”

It helped that, besides a few signs of wear and tear, the house was in remarkably sound shape. “It was in a very good state, for the most part,” says Macey. “The previous owners had taken care of it.”

But Macey, a professional food stylist, wasn’t sure he could work with the Esherick-designed kitchen. “It is a tough kitchen to use every day, just because of how beautiful it is,” he says. “The previous owners didn’t cook very much and went out to dinner a lot — take-out is a great form of preservation.”

So before they even closed on the house, Macey and Savidge sought help from the Philadelphia Historical Commission — the house is locally certified historic — and Bill Whitaker, a Kahn expert and curator and collections manager of the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. Almost immediately, they realized they’d need to find an architect willing to take on a Louis Kahn project.

“Finding an architect proved to be more difficult than we expected,” says Savidge. “We talked to close to 10, and some were hesitant to take on the project because of the responsibility of preserving Kahn’s design.”

Savidge and Macey ultimately found the right architect in Kevin Yoder of k YODER Design. The designer had experience in renovating modernist homes — he restored his own I. M. Pei-designed townhouse — and was willing to work with the couple and a large team of contractors, restoration experts, and the Historical Commission.

Yoder admits he took the project on with a mix of both excitement and apprehension. “My first thought was, ‘Do they know what house they’re buying? Do they understand the significance of the house and the kitchen?’ But it wasn’t too long into the conversation that I realized they had already done their homework and knew of its significance,” Yoder says. “They expressed their philosophy of stewardship to and conservation of the house, as well as a need to bring it up to date for their uses.”

The restoration’s biggest undertaking involved finding a way to preserve the Esherick kitchen while at the same time incorporating a second, 21st-century kitchen into the home. The most plausible fix, Macey and Savidge concluded, would be to turn the utility room into the new kitchen.

“We weren’t violating any of Kahn’s philosophies,” says Yoder. “So it was the perfect location to make that happen.”

It involved a lot of planning and engineering, though. Namely, the gas meter had to be moved from the inside of the house to the detached carport on the side of the property. Once that was taken care of, construction could begin on the new, galley-style kitchen.

Macey and Savidge wanted to ensure that the new didn’t detract from the old, so Yoder put a lot of consideration into the types and tones of wood used for the new kitchen. “We wanted to differentiate it from the Wharton Esherick kitchen and the Kahn cabinetry throughout the house, but not to the point that it felt discontinuous as you walked through,” says Yoder.

The kitchen cabinetry has a similar warm tone and features a continuous grain pattern to match the original wood finishes throughout the home. There are also no visible pulls or knobs, as Kahn’s cabinetry always used latches or finger holes instead. The soapstone counters are also in keeping with the materials used in the upstairs bathroom.

As for the original kitchen, the couple brought in experts from the Wharton Esherick Museum, who figured out which parts of the room were original and which were added over the years. When the more recent cabinetry was removed, they discovered that the original walls had never been painted.

“The entire house had been painted white inside,” says Macey. “But one of the walls inside the cabinets was not painted, which we learned was Kahn’s original intent. He didn’t like the white paint, and had instead wanted the natural plaster to be visible so that when the light hit it, it could read gray, pink, or purple.”

To restore the walls to their original state, Andrew Fearon of Materials Conservation created a special mixture of colors and faux-painted the rest of the kitchen to match the original plaster.

It’s a testament to the home’s previous owners — and Kahn’s work — that, for the most part, not much else needed to be restored or renovated. Says Yoder, “We basically got rid of years of wear and tear and left what we could in its original condition. We weren’t trying to make it look new. We were trying to bring it back in the best possible way.”

After the 17-month-long renovation, Savidge and Macey moved into the Esherick House. As the new stewards of a Kahn home, they have been ushered into a special community of homeowners — one where restoration advice and remodel stories are swapped.

In a way, the couple has also put themselves in the public eye. They’ll often see groups of people make their way down their leafy street and admire their house from the road.

“We understand that this house evokes a very emotional response from a lot of people — time and time again we meet people who have literally traveled from all over the world to Philadelphia just to see the house,” says Macey. “It’s one thing to see it in pictures, but to experience the light through the windows and have it embrace you and wrap its arms around you…you can only feel that by being there.”

Savidge says that even though they have lived in the home for three years, they are still discovering things about the house and its architect. “We learn all the time, and I hope that we never get to a point where we take it for granted,” he says. “We’re certainly not there now.”

Macey adds, “I think some people have called this the biggest littlest house in America and I certainly know why they say that. It’s a small space, yet it feels monumental.”

Interior Design by Louise Cohen Interiors.