This year, we have devoted New York’s annual “Reasons to Love New York” issue to a celebration of the go-tos that have closed since the pandemic struck. A wake for the places that defined our lives here — that gave us community and let us try on new identities in return for our money. The bars where we came together for after-work drinks, the boxing gym where everybody thinks they’re in an action movie, the gallery that trusted you to build a cloud, the coffee shop where you were left alone to read, the restaurant with the full bar where you’d find yourself trying to eat after an all-night bender, the place that was so of its moment that it became a relic and then (deservedly) an icon. All gone. And sadly, probably, more to come before the city returns to its purpose: a place of gathering. We’ll be sharing these tributes all week on Curbed.

Back in the mid-aughts, before I got priced out of a studio off Malcolm X Boulevard, I lived ten blocks from the historic jazz bar Paris Blues. I would pass by but never stop in, curiosity always losing out to the anxiety of drinking alone. But plenty of other people braved those doors, and for 52 years, Samuel Hargress Jr. would descend from his apartment upstairs and get the place ready for them. The bar opened at 3 p.m., and the live music would start at nine o’clock and go on until one in the morning, though Hargress usually called it a day around 10:30. If he hadn’t gone back upstairs by midnight, he was having a good time. He died in April, the day after his 84th birthday, from what doctors, lacking tests at the time, presumed to be COVID-19.

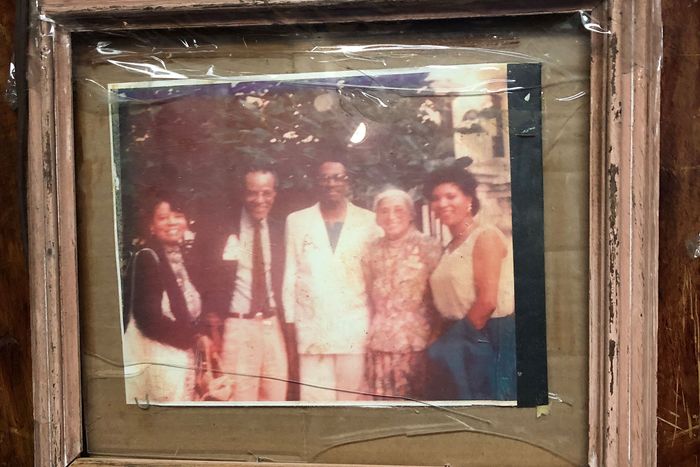

Hargress — Mr. Blues, as some called him — was a lot of things. He was a Black man from Demopolis, Alabama, who marched behind Dr. King and John Lewis in Selma on Bloody Sunday. (He learned to work wood in Alabama; the distressed-wood cladding that wraps the bar’s façade, the knotty rafters that surround the stage like a farmhouse porch, and pretty much everything else wooden in the bar he made by hand.) He’d been stationed at Checkpoint Charlie in Germany with the Army, a fact he never failed to mention to the tourists who posed with him amid a riot of nostalgic bric-a-brac and framed proclamations and portraits. Sam, stoic in his Army uniform. Sam standing beside Rosa Parks. Sam smiling with a then-unknown Kacey Musgraves. His dream had been to open a bar even though he never drank alcohol or smoked. He ran Paris Blues despite having no aptitude for music. “He can’t sing, he can’t dance, he has no musical talent,” said his son, Samuel Hargress III, whom his father called Little Sam. “But that was his love.”

Before Paris Blues opened for the day, Hargress would usually meet his friend William Palmer at IHOP with a piping side of political debate. “Oh God, I miss the guy,” Palmer told me. A “debate” often meant sparring with Hargress over his unflagging support for Donald Trump. They would continue their heated discussions into the evening at the bar, often drawing an audience before the music began. “He was a pain in the neck,” Palmer said. “But he was my pain in the neck.”

The Hargress family owns the landmarked building and has no intention of selling it. Little Sam, who has taken the reins of his father’s business while working full-time for New York City Children’s Services, intends to reopen it. But, still haunted by the memory of watching his father die alone over FaceTime in a medically induced coma — “To know that he got sick, went into the hospital, and eight days later he was gone, I think that shook me to the core,” he says — he’s in no rush. Meanwhile, the real-estate speculators are calling. “Every day I get a different offer.”

Alphonso Black, who grew up with Hargress in Demopolis and now lives on the fourth floor of the building, is eager to see the bar up and running again. Before COVID, you could find him every night singing and blowing his horn on the stage his childhood friend built. A contractor by trade, Black has been keeping an eye on the bar and managing the building since Hargress’s passing. Before we got off the phone, he invited me by to hear him play when it’s safe again. “I practice every day,” he said.

*This article appears in the December 7, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More Reasons We've Loved New York

- Farewell to That Gentrifying Harlem Restaurant I Really Won’t Miss

- Farewell to My Brick and Mortar Shops

- Farewell to China Chalet, the City’s Hottest Dim Sum Disco