This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

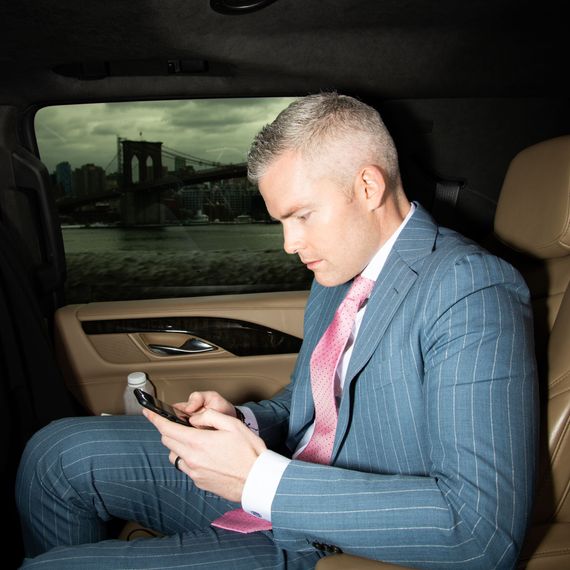

Ryan Serhant wanted to elevate. On an unseasonably beautiful winter morning, the real-estate broker was gliding around the rooftop terrace of a penthouse in Soho, trailed by a two-man camera crew and sizing up the angles. He hoisted himself above the terrace wall, placing one Prada boot on a planter, the other on a piece of wicker furniture. “This way,” he said, “I’m in the sun.” Serhant wore a light-blue pin-striped suit, a baby-blue Hermès tie, and a brilliant white smile, which I could see because he had stripped off his navy-blue mask, which was branded with an S. From the knees down, he was contorting to hold himself steady. But his upper half was bathed in light, with the Empire State Building framed over his shoulder.

Serhant, who is 36, makes his living selling luxury apartments, and he does it through the force of his personality, which flows like a torrent through many channels. A longtime star of the Bravo series Million Dollar Listing New York, Serhant has 1.5 million followers on Instagram and a million subscribers on YouTube. He is into video production and motivational speaking. The self-promoting performance is all meant to support his new brokerage, Serhant. (that’s not the end of this sentence — the period is an emphatic part of the brand). He calls it “the future of where real estate, tech, and media collide.” Launching a firm to cater to a tiny, ultrawealthy stratum may sound counterintuitive at a time when spindly new condo towers stand empty and swaying and the city’s status as the global center of culture and wealth is uncertain. But Serhant knows how to create his own reality.

“Rolling,” said one cameraman, who was perched above him on the building’s roof.

“Rolling,” said the other.

Serhant breathed deeply and composed his face. He has the perfectly proportioned features of a soap-opera actor, which he once was, and a prematurely silver shock of hair.

“Boy oh boy, do I have a surprise for you,” he began, eyes widening. “You don’t even know what’s below my feet right now. Like, you have no idea. Right now, you see me on this terrace. Maybe you know where I am. If you tilt it a little bit this way” — he paused as one cameraman panned to the water tower on top of a neighboring cast-iron building — “you can see that I’m actually in the heart of Soho, and what I’m standing on is 1,163 square feet of private roof space in Soho in a brand-new penthouse that we’re going to be bringing to market very, very soon. It’s 4,270 square feet interior, four beds, four and a half baths, amazing outdoor space, private hot tub, outdoor TV, fireplace, everything! I am going to blow your mind. Here … we … go!”

The sellers, a California couple, had purchased the penthouse as a pied-à-terre in 2018. “I sold it to them for 14,” Serhant told me when the camera was off, “and now they’re not here anymore.” With the exception of a few personal accents — the model of a private jet, a framed photo of the couple in front of the actual jet — there was little to suggest the place had ever been inhabited. Serhant said he thought he could sell the apartment for around $15 million, which seemed optimistic considering the pandemic had driven away foreign investors while pushing wealthy New Yorkers to out-of-town retreats. But Serhant claims he can still find buyers where they really live: on their phones.

The property in Soho had not been officially listed for sale. “Nobody knows about this yet,” Serhant told me. But once it did go up, the broker intended to blast out the video to his many millions of fans and followers. The tour continued down to the living room, with its wraparound windows, through a pair of pocket doors, which he opened with a stagy flourish, and into the kitchen, which was clad in white marble. The owner had “completely ripped it apart,” Serhant said, “because he wanted to create the greatest chef’s kitchen in the world here in Soho.”

Serhant continued down to the apartment’s lowest floor, where there were three bedrooms, including one that was outfitted as a mini-gym with a Peloton, and another terrace with a green wall. “We gotta go, gotta go, gotta go,” he said, urging on the cameramen as they set up the shot. Serhant was late for his next appointment. He finished up in one fast, extemporaneous take. Before he left, though, he pulled out his camera and shot another bite-size video clip to post to his Instagram Stories. “So beautiful, so big,” he said, as he walked through the bright living room.

“Where’s that emoji?” Serhant asked. He found the one he was looking for: a yellow face holding up a shushing finger. COMING SOON, the text over the video read. DM FOR DETAILS.

I was still with him a couple of hours later, when he looked at his phone and told me he had just gotten a message: A former client had forwarded the Instagram post to a couple that was looking to buy in Soho, and they wanted to see the place before it listed. A few days later, he would tell me, the interested party had taken a tour and, shortly after, had made an offer. The penthouse has never hit the market.

“I mean, 2020 was the greatest opportunistic market I’ve ever seen,” Serhant said. “It’s about finding good deals and presenting them to people who are looking for good deals, and I’ve kind of become, like, the billionaire go-to when it comes to real estate.”

You should never totally believe your eyes when you look at reality television or social media or, perhaps most of all, New York real estate. While the sales on Million Dollar Listing are real, I was told by people who have appeared on the show that some of the negotiations are reenacted with the treachery amped up. And the world of luxury real estate — where no one ever seems to be at home, everything is owned by anonymous shell companies, and figuring out transactions is like following the coin in a magic trick — is itself a realm of illusion.

It would, however, be wrong to assume Serhant. is just an act. “It’s definitely performance art,” says luxury residential developer Michael Stern, who is friendly with the broker. “But there’s a seriousness underpinning it.” And real-estate opportunities really do abound in New York City right now — although, as always, there’s a catch.

According to the most recent market report from the brokerage firm Douglas Elliman, more than 8,000 properties were for sale in Manhattan at the beginning of this year (more than double that if you count unlisted shadow inventory), a glut comparable to levels last seen in 2008. But the excess of supply hasn’t brought down the cost, in part because most affluent people are doing fine financially. If you have a classic six on Park Avenue or a condo in Battery Park City on the market, you’re probably not selling at a discount right now unless you’re leaving the city for good or going broke. Consequently, the median sale price of a Manhattan apartment in the fourth quarter was a little more than $1 million — actually higher than what it was during the same period in 2019 and not too much below the record of a few years ago. In most segments of the real-estate market, it’s not a bloodbath. It’s just blah.

The exception lies in the luxury market, which is generally defined as the top 10 percent of any property class. The reasons stretch back more than a decade before the pandemic. After the 2008 crash, there were more than 10,000 co-ops and condos on the market, many of them in new developments started during the debt-fueled speculative mania. But the real-estate industry was rescued by a great flood of investment capital, much of it from overseas sources. A new global plutocratic elite was emerging, and it wanted to buy in New York, which was perceived as a safe haven for wealth. Developers erected skyscrapers like One57 and 432 Park Avenue, and they were marketed to an absent superrich clientele so successfully that the title Million Dollar Listing would come to seem as quaintly dated as Dr. Evil’s ransom demand.

No one saw fit to stop and ask whether there were enough billionaires out there to absorb all the ultraluxury product. Eventually, reality intruded. Sellers began to outnumber buyers. New developments, which have to sell out quickly before developers’ loans start coming due, were especially imperiled. At the end of 2019, the median sale price of a Manhattan luxury unit, $4.8 million, was 30 percent off its high. And that was before the lockdown, which sent the entire market into paralysis. Manhattan sales activity saw its steepest decline in 30 years during the second quarter of 2020 and remained at that level through the summer. This created an opening, though, for a very specific type of New York buyer — the luxury-deal hunter. As usual, the people who have the most money are getting the bargains.

After he finished his video shoot in Soho, Serhant climbed into a chauffeured SUV and was off to his next stop, 565 Broome Street, a new luxury-condo development designed by Renzo Piano. “I just sold the penthouse,” Serhant said, “and apparently I have to check and see if the pool’s been winterized.” He represented the buyer, whom he identified as a “New York finance” person. (Property records indicate the buyer was an entity called Feynman Point LLC, which appears to be associated with the manager of a New York–based hedge fund.) The penthouse next door sold for $36.5 million in 2019 to Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick. This one listed at $30 million before the pandemic. Serhant’s client knocked the price down to $22.5 million.

The 25 percent discount was large, but such deals are not unheard of. During the fourth quarter, luxury units sold on average at almost a 10 percent discount from their list price. As a result, there has been a notable uptick in sales activity. This January, there were 52 apartment sales of more than $5 million apiece recorded in Manhattan, compared to 38 in January 2020.

Serhant and I rode the elevator to the penthouse. The doors opened to a 16-foot window wall with views across Manhattan. The space was completely empty. He took me up a flight of stairs to show off the view from a mezzanine that projected over the living room. “This is your master-and-commander position here,” he said, looking west. “That hole is Disney,” he added, pointing to the site of the company’s future headquarters on Varick Street. “Those cranes,” he said, pointing toward the West Side Highway, “that’s Google.” He went up to the roof to check the pool for his client.

“A big part of my job is trust with high-net-worth people,” Serhant said. “He’s never been here.”

Wait a minute, I thought. A New York financier bought a $22.5 million apartment he had never visited? That seemed implausible even in a pandemic. “The only time he ever saw the apartment,” Serhant later clarified, “was for the six minutes when I showed it to him.”

Was that normal?

“For me,” Serhant said, “yeah.”

Other brokers speak of Serhant with a mix of respect and enough competitive cattiness to indicate his arrogance is justified. When Million Dollar Listing first came on the air, he was completely unknown in the industry — just another handsome striver selling condos in the Financial District — and many still sniff at the show’s cheesier elements. For the series, Serhant wears silly costumes and stages entertaining stunts. He takes off his shirt a lot. “These reality-TV shows are great for launching the careers of people who otherwise might not have had much of a career,” says Leonard Steinberg, an executive at the brokerage Compass. “What it does that makes me crazy is it’s bastardized the profession.” He complains that the show leaves out all the boring, respectable work, making it look as if every deal were filled with cutthroat antics — although, come on, this is real estate. “Our industry is not exactly known for employing nuns and monks,” Steinberg admits. He recalls that he once appeared with Serhant at an industry panel discussion held at the penthouse of 212 Fifth Avenue (subsequently bought by Jeff Bezos). He remembers Serhant saying there was little difference between salesmanship and acting: “He says, ‘This is just bullshit — it’s all bullshit.’ ” (Serhant recalled the event but denied saying this.)

When I told Steinberg about my visit to the penthouse in Soho, the Instagram post, and the serendipitous message from an interested buyer that just happened to come in my presence, creating a perfect distillation of the Serhant way of real estate, Steinberg laughed. “It might be a good idea to check it,” he said. “Very few deals happen, especially in the Manhattan market right now, before something gets listed.” When last we talked, Serhant said the deal was “still in negotiations.” He swears it is all happening, but there is no way to verify it — real-estate transactions don’t become public record until they close.

“I don’t need that sale to justify myself as a real-estate broker,” Serhant said, adding that his competitors don’t understand his social-media power. “You give 3.5 million followers to any of these people, and all of a sudden, their tune is going to change.” The weird thing is even detractors of Million Dollar Listing and Serhant will admit that, over time, the show’s presentation of the industry has become more true to life. The bullshit reality has bent real reality, and a onetime nobody has transformed into a genuinely prolific deal-maker.

Early on, I was going to quit the real-estate business a lot,” Serhant recalled in mid-December, speaking into a large, radio-style microphone at a Zoom event for early purchasers of his new book, Big Money Energy. He described how he had learned to project the aura of “who I want to be” until that cloud condensed into a downpour of riches. Serhant describes his life as following a familiar uplifting arc: He grew up on a farm, he often says, worked on a ranch during his college summers, and lived a penniless existence when he first came to New York to try to make it as an actor. He scored a few parts in plays and on TV and got work as a hand model but decided to try real estate after a dispiriting production of Romeo and Juliet in a park next to the West Side Highway. He started to work at a small brokerage firm called Nest Seekers International. He could afford only one suit. He faked it and then he made it.

“In 2008 my annual earnings were $9,188,” he writes in the book. “After designing a whole new Ryan, and going BIGGER, ten years later I am earning a million dollars every month!”

Big Money Energy includes a chapter titled “The Art of Selective Communication,” so it’s not surprising that this history omits a few details. Serhant’s father worked at State Street Global Advisors, a Boston asset-management firm, and headed its department for high-net-worth clients when Ryan was a teenager. The family farm was in Topsfield, one of the richest towns in Massachusetts. The ranch, in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, also belonged to his parents.

“It was a nice farm, but we grew up on a farm,” Serhant told me. “And we had to work the damn farm, and it sucked.” He said his parents — his father, especially — had instilled him with his work ethic, which is truly Bunyanesque. He started out doing cheap rentals and clawed his way into selling condos, making a standard commission. “I remember distinctly people being mean to me,” he said. “Brokers were tough because they had never heard of my brokerage.”

Then Serhant saw an ad for a casting call. Million Dollar Listing, the Los Angeles–based reality show, was doing a New York spinoff. He had already appeared on a reality show that had contestants competing for a part on the soap opera As the World Turns. (He won and was cast as an evil biochemist who was quickly killed off.) Most large brokerages, meanwhile, were telling their agents not to audition, thinking the show would look déclassé.

Serhant said the first season, shot in 2011, was a ruthless competition. The producers cast four brokers and told them only three would make the final cut. To secure his spot, Serhant decided to behave outlandishly, like an untamed bro. “I saw Ryan’s casting, and I thought, Oh, I want to watch him,” recalls Shari Levine, a top network executive involved in production. “He’s an attractive man, he was aggressive, and he would do whatever he needed to make a sale.”

By the second season, Serhant had become the core of the series, along with Fredrik Eklund, a similarly brash and telegenic Swede who worked at Douglas Elliman. They invited Bravo’s cameras into their deals and their lives, or at least into a reasonable simulation of them. The cameras were there when Serhant got married to Emilia Bechrakis on an island in Greece. (A pirate ship was involved.) Later episodes chronicled the couple’s fertility treatments, and the most recent season began with a successful pregnancy test. At first, other brokers found the show schlocky, but then they started to notice Serhant was selling a lot of real estate.

“I’m a firm believer that you have to be the role before you are the role,” Serhant said as we drove around Manhattan, chauffeured by his silent Russian driver, Yuriy, a fixture on the series, who has 16,000 followers on Instagram.

When the market started to tank, it only enhanced the appeal of a broker like Serhant and his social-media influence. “Ryan is well positioned to say, ‘Well, the broken system that you had before wasn’t working, so why don’t you try something new, something more modern?’ ” says Michael Stern, whose current projects include Steinway Tower, a needle-thin skyscraper on West 57th Street. “He knows how to cut through the noise, get attention, and get eyeballs.” Sure, most of the people in that mass audience are just voyeurs, but it includes a lot of real-estate brokers, and at least some of them represent buyers who, though rich, still get a thrill at the prospect of meeting someone from TV.

What is maddening, Serhant said, is that in early 2020, the luxury market seemed like it was picking up. “Everything was going to be great,” he said, “and then boom.” In March, he was shooting Million Dollar Listing and had just sold Marc Jacobs’s West Village townhouse at a (reduced) price of $10.5 million. “We closed on a Friday,” Serhant said. “A week later, Cuomo shut down the city.”

Bravo halted production of the ninth season. (It restarted in the fall.) The governor’s lockdown order prohibited in-person showings. Serhant was just trying to hold existing deals together. He and Emilia have a toddler — their daughter, Zena, is almost 2 — and his mother-in-law was living with them. They got out of their apartment in Soho and drove to New Hampshire, where Serhant’s parents owned a cottage on a lake. He typically wakes up at 4 a.m. to get in an intense gym workout and hurdles through his day in 15-minute increments. Suddenly, he was grounded. “I was stuck in the woods,” he said.

Out of this Walden, he said, came Big Money Energy and a bold plan for his future. In September, he announced he was launching his new company. At Nest Seekers, he had overseen a team of 65 agents, which he said generated $1.4 billion in sales in 2019. Still, Serhant wanted to have his name on the marquee.

“I consistently put myself in uncomfortable situations,” he told his Zoom audience at the book event in December. “Like, what am I doing? Am I starting a real-estate company in the middle of a pandemic in New York, when a million people just left the city?”

“What am I, nuts?” Serhant said. “Yeah, I am kind of nuts.”

Serhant’s books — before the latest one, there was Sell It Like Serhant — are full of motivational parables about the lengths to which he will go to sell himself. There’s the story, for instance, of an unidentified developer who was building a project in Brooklyn that Serhant wanted to represent. He writes that to get the developer’s attention he shipped him a large “architecturally interesting” bookcase and sent him a book for it every day, each with a thoughtful inscription. Finally, the developer texted, “U WIN. LET’S DO IT. BOOKS CAN STOP NOW.” I assumed this story could not possibly be true, but then Stern told me he was the developer in question. “I think he sent me a thousand books,” Stern said. “At first, I laughed. And then it was annoying. And then I came around to respecting it.”

Serhant once threw a Back to the Future–themed party, complete with a DeLorean, to promote a townhouse with 1980s décor. He hired a marching band to perform at an open house for a property located next to the racket of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. He has used skywriters, daredevil stunts, and hundred-foot banners of nude models in body paint. Roxanne Donovan, the chief executive of Great Ink Communications, recalled that when Serhant was brought in to revive a stalled residential development her firm was representing on 59th Street, he suggested spicing up its tasteful interior renderings by Photoshopping in women in G-strings. “But it didn’t make me hate Ryan, which is what was surprising to me,” Donovan says. “He is unapologetically an animal at selling things.” (Serhant said he never would have proposed something so crass but agreed he was an animal.)

People who have worked with Serhant say his Bravo-style showmanship coexists with a careful business instinct. “He’s very sophisticated in his approach,” says Al Tylis, a former commercial-real-estate executive who has used Serhant as a broker for five personal transactions over the years, including his purchase of a $31.5 million condo at 520 Park Avenue. “It’s very workmanlike and non-showbizlike. It’s all business; it’s getting it done.”

“The guy has a great work ethic,” says Oren Alexander, a star broker at Elliman who specializes in selling trophy properties. “Ultimately, he just worked it and figured out how to play his character and work that character into creating a big business.” Alexander makes sure to add, though, “He’s more of a volume guy.”

At the moment, with so much business activity still frozen, most people in real estate would kill to say they have volume. This winter, many brokers have followed the action to Florida, which is swelling with wealthy COVID refugees. Serhant and Alexander recently negotiated a deal for a $33 million penthouse in Miami. (Serhant said the buyer, a New York financier, found him via his daughter, one of Serhant’s YouTube fans.) This month, Serhant represented a relocating New Yorker who bought a newly constructed Palm Beach mansion for a reported $132 million, according to Bloomberg. (The beachfront property was formerly owned by Donald Trump, who flipped it to Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev, who ultimately sold the land to the mansion’s spec-home builder. Florida!)

The Serhant. office is located in a renovated five-story townhouse in Tribeca. When I arrived there on a weekday in January, the first thing I noticed was there were a lot of people in it. Since the governor allowed the real-estate industry to go back to work in June, it has basically returned to business as usual. Brokers really have little choice; they are merely intermediaries between wealthy parties, and they can easily be replaced.

Serhant was in the room he uses as a studio, taping an episode of the Big Money Energy podcast he is developing. One of his team’s cameras was trained on his naked face. Everyone else in the office kept their masks on, but Serhant takes his off when he’s on-camera, which is often, because he is constantly shooting content for his in-house video operation, Serhant. Studios. Besides his own marketing content, the venture produces a series of reality-style programs for Listed, Serhant’s YouTube channel. “I now get more business from YouTube, mixed with Instagram, than I do from Bravo,” he told me, adding that Listed also serves as a tool to recruit brokers to his company. “I can give them their own shows.”

Serhant is proud to note that the office has no desks for agents, just couches. In a cafélike room on the top story, people were working on laptops at closely spaced tables separated by plexiglass barriers. On the ground floor, I sat in on a brand-strategy meeting in a conference room with Serhant and a half-dozen members of a broker team he had lured away from a competitor.

Brokers report that, with the New Year and the hopeful news about vaccines, they see signs of a rebound. Serhant made the argument that being confined for months on end has made many people crave better surroundings, and many of them have been getting their vicarious fix from him. “I am a passive friend for people around the world,” he said. The scale of that social-media following, he explained, is his market advantage. “As I look at other brokerages and agencies, as they cast a net, they all cast a net in the same exact place,” Serhant said. “If they are going to pay a brokerage commission anyway, why not hire the guy with the biggest net?”

This pitch holds desperate appeal for New York’s residential developers. Such projects are extraordinarily expensive to build and are financed with loans that must be paid back within a relatively short time. Already, one very active developer, HFZ Capital Group, has lost several buildings to foreclosure and, according to Crain’s New York Business, appears to be on the verge of relinquishing its high-profile project next to the High Line, a pair of twisty towers designed by Bjarke Ingels. Because the yearslong schedule for construction lags behind the market, there are more buildings on the way, and they’re about to arrive at the worst possible moment.

Marketing new developments is a major focus of Serhant’s firm. During our day together, he zipped from one construction project to another, donning a hard hat to check out the progress at 101 West 14th Street, then heading to a sidewalk marketing meeting outside 199 Chrystie, a new building by Danish architect Thomas Juul-Hansen. The design called for 14 “interlocking villas” with floor-to-ceiling windows looking out on Sara D. Roosevelt Park, that brick-and-Astroturf island that runs from Houston Street to Canal. “We’re marketing it as a dynamic neighborhood,” Serhant said. A man pushing a cart full of junk passed us in the bike lane. “Irrespective of economic cycles, there’s always a flight to quality.”

The market appears to have turned decisively against the super-tall condo towers that symbolize the excess of the past decade’s luxury-building boom. If you are interested in living at 432 Park Avenue, now may be a good time to make your offer. The New York Times recently published a front-page story describing a devastating litany of plumbing and engineering complaints from residents of the nearly 1,400-foot Rafael Viñoly building. “Listen,” Serhant said in its defense, “if you take a significant amount of superwealthy people and you stack them all on top of each other, for the slightest thing to go wrong — they’re very, very needy people, and if things are not perfect, perfect, perfect, then they’re terrible.” But the depreciation isn’t limited to one shaky building. At One57, the first tower built on midtown’s “Billionaires’ Row,” apartments have lately been reselling at deep discounts, according to real-estate appraiser Jonathan Miller. In December, Unit 58A, originally purchased for $34 million in 2014, sold for just $16.8 million, a 50 percent loss. Serhant represented the buyer.

“That is a blip in time,” Serhant said as we rode past storefronts covered with deathly brown paper. “That type of deal won’t ever exist again.”

We next headed to Brooklyn Point, a new tower near Fulton Mall, built by Extell Development, the firm behind One57. The apartment tower, now the tallest building in the borough, was Extell’s first in Brooklyn. The company’s chief executive, Gary Barnett, is a famously secretive former diamond trader, and he had used his own sales team to discreetly market developments like One57. Of course, that was in a different time, in Manhattan. After opening Brooklyn Point in the midst of the pandemic with predictably middling sales results, Barnett hired Serhant.

Serhant announced that he was taking over sales in the building in November with a whoosh-filled YouTube video. “Boom!” he says as he signs a contract, slaps his hands on a table, and high-fives an employee. “Our first new development signed as a new firm.” Then the video cuts to a brainstorming session, where Serhant and his team bounce around wacky marketing ideas. (Parachutes?) After a tour of the building that shows off its incredible gym and other amenities, the video culminates next to the rooftop infinity pool, which is purportedly the highest in the Western Hemisphere. A string quartet plays “Empire State of Mind,” and a ballerina dances en pointe. As one of his assistants sends the scene live to Instagram, Serhant introduces three masked Extell executives, who look awkward.

“I think it was a very creative and effective way of highlighting one of the attributes of the building,” says Ari Goldstein, a senior vice-president at Extell who appeared in the video. But he says reaching people through social media is just an initial step. The real trick is conversion: turning that brand attention into actual transactions. This is where Serhant’s new approach meets the true reality of the marketplace. Ultimately, most real-estate sales come back to fundamentals; it’s a physical business.

“Ryan acknowledges that,” Goldstein says. “That’s the first thing he says: ‘My job is to get people to see how great the building is by coming to the building.’ ”

Another fundamental is location, which would look to be a challenge for this building, which is located in a charmless commercial district. Serhant had invited a couple of brokers from competing firms to have a look-see. As we waited at the front desk, Serhant mentioned he would soon be moving to nearby Boerum Hill. “I bought Jonathan Safran Foer’s house,” he told me. The novelist was asking $9 million for the place with Serhant as his broker. Serhant decided he liked the building’s bones. (He paid $7.6 million.) He has spent the past two years renovating, ripping the whole house apart and installing a gym in the basement.

The other brokers arrived, and we took the elevator up to the model apartments, instinctively moving to the four corners of the box and riding for what seemed like an uncomfortably long time. The views were remarkable, as advertised: a perspective on New York like I had never seen, with Manhattan splayed out in one direction and a glimpse of the Atlantic Ocean in the other. “This apartment starts at 2.7,” Serhant said, speaking without any salesmanship since these were other professionals. “We’re getting a lot of investors.”

The other brokers seemed mildly impressed behind their masks. When Extell hired Serhant, only 10 percent of the building’s 458 units had closed. Goldstein says there has been “a giant uptick in every statistic” since then. “People are able to get great deals now,” he says, “that they weren’t able to get before.” Still, there’s a lot of inventory to burn through. And given the pandemic, constraints on travel, and the changed geopolitical climate, it seems unlikely that outsiders will be coming to save the market again. The New Yorkers will have to work it out.

“What it’s doing is, it’s wiping the slate clean,” Serhant said. The crisis gripping the city is opening up opportunities for those willing to commit to it (or at least the select group of people who have the ability to spend millions on an apartment). In the process, it is introducing new characters, new ways of thinking, to the show. Serhant walked out of Brooklyn Point still talking, crossing the street without looking in either direction and coming close to being hit by a car. “It’s supercool now,” he went on, after we got back into the SUV. “I am such a firm believer that the agent brand comes before anything else.” Then he pulled out his phone and took off his mask so he could speak, unmuffled, about Big Money Energy with a producer for Dr. Oz.

*This article appears in the February 15, 2021, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!