/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/57083945/slack_imgs.0.jpg)

When 33-year-old Carolina Wong graduated from Florida State University in 2006, she had a plan. She would take her degree in advertising and her love of good design, work hard, and become a graphic designer.

The realities of the working world, and her industry, quickly altered her best-laid plans: Two years as a marketing assistant and then account executive steered her into a more marketing-oriented role, work that both “drained her soul” and wasn’t very well-paying.

Wong hit a breaking point, decided life was too short to do work she disliked, and made a move that is increasingly common among her millennial peers: She decided to move home, live with her parents, and reset. According to Pew Research Center analysis, 15 percent of 25- to 35-year-old millennials were living in their parents’ home in 2016, a much larger share than members of Generation X, born 1965 to 1979 (10 percent), and the Silent Generation, born 1925 to 1945 (8 percent), at the same age.

“I didn’t feel like I had any other option,” Wong says. She moved back with her parents in Hollywood, Florida, and ended up staying for five years, aiming to rekindle her love of film and pivot to a new career path.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9426963/cb17_tps36_young_adults.jpg)

Wong remembers hesitating at first; despite her close relationship with her parents—which was only strengthened by moving back in—she was unsure about the move.

“That was a big struggle from me,” she says. “I didn’t want to feel like I was leeching off them. At first I dreaded it. I remember crying to my mom and discussing why I didn’t want to do it.”

Now, at age 33, Wong has a much different viewpoint after living with her parents, in many ways mirroring how social expectations and views about “boomerang” kids coming back home has shifted in just the last decade. During her time at her parents’ house, Wong was able to save enough for a down payment and buy a home, located eight miles away in Sunrise, Florida. She also parlayed experience working for local production houses on commercials into a full-fledged career as a stylist, costumer, and costume supervisor designer for film and television; after working on shows such as The Walking Dead in Georgia, she’s on the cusp of buying a second home in that state, and will soon own two homes as she navigates a more permanent move north.

Like many her age, Wong saw moving home as a route to more financial security in an increasingly insecure economic environment. She’s even counseled younger coworkers who are agonizing over making a similar choice, assuring them that it’s not a bad idea.

“If you have somebody who’s willing to help you, don’t be embarrassed by it,” she says. “I think it’s a smart decision if the help is there. There are a lot of people who don’t have that kind of help. It’s like a stepping stone; it’s not a permanent thing.”

For a generation of young adults facing the hurdles of a changing and insecure economy, there are also the barriers of rapidly rising urban housing costs and staggering loan debt (education debt alone, which has doubled since 2009, has caused a 35 percent drop in millennial homeownership, according to a New York Fed study). Add the hangover of the Great Recession and the idea of moving back home has gone from Exhibit A of this generation’s ostensible entitlement, laziness, and narcissism to something more accepted, nuanced, and less stigmatized than it was even a few years ago.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9426927/preview13.jpg)

Last year, Pew research found, for the first time ever, living at home with parents had become the most common living situation for adults age 18 to 34. As census data suggests that young adults moving back home is more and more common, and many researchers believe it’s a trend that’s here to stay, it’s increasingly important to see the changes for what they represent, especially in terms of the real estate and housing markets, rather than as a sign that the kids simply aren’t alright.

“We don’t hear that stereotype of the lazy millennial discourse in the media like we did five or 10 years ago,” says Dr. Nancy Worth, a researcher at the University of Waterloo who helped compile Gen Y at Home, a 2016 study of young adults living at home in the greater Toronto area. “Now, you’re hearing how smart, strategic, and lucky young people are for staying home. It’s seen as the smart, strategic choice.”

As challenges with affordable housing and a lack of starter homes persist (inventory has plunged 40 percent since 2012), the millennial and Gen Y response—including living at home to save money and reduce debt in efforts to afford a home—can be seen as a strategic reaction to larger economic shifts.

“It’s not a reflection on the millennials; it’s a reflection of where we are as a society,” says Derrick Feldmann, a researcher who has conducted extensive studies on younger adults as part of the Millennial Impact Project.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9426951/geny.jpg)

An “idle” generation that’s actually more resourceful

Feldmann’s research and marketing firm, Achieve, has spent years working on a large-scale survey of millennial attitudes about social causes and values. Overall, their research has found that millennials see themselves as more socially engaged and active than their family members. He also found that there’s more acceptance toward living with parents, in part as a recognition of economic realities.

“It was never socially acceptable for boomer parents to go into debt to go to college,” he says. “Today, it’s socially acceptable, and, in fact, boomers are the ones encouraging young adults to go through with these sorts of arrangements.”

Expectations, not surprisingly, shape how young adults view their decisions to move home. Worth says her research found that in Canadian cities—which face many of the real estate price pressures common in big U.S. cities—the combination of high rents, the difficulty in getting a down payment together to “get on the property ladder,” and the increase in part-time and contract work in the gig economy has led to a record-high number of young adults living with their parents. In Toronto, for example, 1 in 3 young adults lives at home.

“If you’re putting together a freelance career, it’s hard to sign on a dotted line when you don’t know where the money is coming from,” she says. “A report from a Canadian group called Generation Squeeze found that, to get the standard 20 percent down payment on a house, it took young people five years in 1976. Today, that’s 15 years in Toronto (and 23 in Vancouver).”

Worth says many of the respondents in her survey said that living at home “felt like a step sideways.” This wasn’t how they envisioned their late 20s or early 30s, but it’s the reality of today’s economic landscape.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9426973/time_to_save_2016.jpg)

Part of a larger developmental delay

Young adults are entering the workforce at a precarious time. The triple threat of high income inequality, high housing prices, and high student loans certainly comes into play, says Dr. Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and author of Generation Me, iGen, and a recent Atlantic article about the impact of smartphones. But another aspect of this larger shift is more cultural and psychological. Raised with a more individualistic culture, younger adults are delaying romantic partnerships, cohabitation, and having children.

“The entire developmental pathway has slowed down,” she says. “Younger kids aren’t given as much independence and responsibility as they used to, and it’s taken longer to grow into adulthood.”

Those young adults coming after the millennial generation, whom Twenge has called iGen, is “putting off adulthood in every way.” They’re less likely to get a driver’s license, date, have sex, and drink alcohol, at the same age as previous generations. Twenge doesn’t want to make predictions as to whether the number of young adults living with parents will continue at such high rates. But she says some numbers are telling; the U.S. birthrate is showing more births among women in their later 20s than early 20s.

“That’s a fundamental shift as to when people are having children,” she says. “That’s where I’m willing to make a little more of a prediction: I believe that’s going to continue.”

With this kind of big shift, there’s a lot less stigma for a 25-year-old to live at home, since so many of their peers are doing the exact same thing.

In addition, as young-adult populations in the United States and Canada become increasingly diverse, with larger numbers of Latin Americans and South Asians, the rise in intergenerational households, and adult children living at home, is also a factor of cultural choice and cultural norms. Worth’s studies in Canada found that 1 in 3 respondents said they wanted to be at home, and there’s a lot to be said about Generation Y making that choice instead of being resigned to it.

“It’s mutual reliance; it’s a two-way back-and-forth support, for housework, errands, getting the groceries, and sharing the tasks of running a home,” she says. “You’re starting to see the beginnings of intergenerational households.”

For Carolina Wong, being closer to her Peruvian-Chinese family, and even being “protective,” of her parents, was a huge benefit.

“The very first week I was in my own house, I went home to my parents’ house every day,” she says. “It didn’t feel right. I still call the parents house home.”

She’s not the only one to feel that way. According to 2015 figures from the National Alliance of Caregiving and the AARP, millennials now make up a quarter of the 44 million caregivers in the United States, defying stereotypes of older adults taking care of each other.

Worth says that the rise in intergenerational living is a result of more than just young adults living at home. Decreasing mobility in the U.S., boomers staying in their homes instead of retiring and moving, portends a future of much more intergenerational living. Worth says that North Americans have a lot to learn from places such as Japan and Scandinavia, where co-ops and shared space are more common.

“I think it’s important to go beyond the hard data, and talk to people about how they feel about these changes,” she says.

Diversity, minorities, and the wealth gap

As statistics show the “boomerang” millennial is in fact a more common occurrence than many think, and media perception is catching up to the reality of more young adults living with their parents, perhaps another aspect of this story will get wider appreciation: the diversity—both culturally and economically—of those moving back in with their parents.

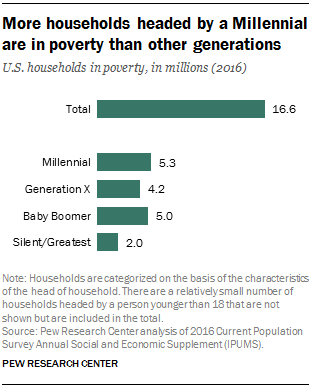

Running very contrary to the notion of millennials as a spoiled generation, Pew research notes that the number of millennial households in poverty is troublesome. In 2016, an estimated 5.3 million of the nearly 17 million U.S. households living in poverty were headed by a millennial, more than any other generation. And a majority of single-parent households were also millennials. Richard Fry, a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center, says this demographic difference is a big factor in the high number of millennials living at home: it’s not as much a failure to launch as a lack of resources keeping them away from the launch pad.

“It’s not the college-educated ones that are most likely to live at home,” he says. “It’s those who ended education with high school diplomas. It’s a disproportionately non-white, less educated part of the population. They’re doing this because they don’t have the skills and the wherewithal to live independently.”

Look at California, where 38 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds live at home (that’s 3.6 million young adults). According to research by CALmatters, a nonprofit media source, 70 percent of the 25- to 34-year-olds at home are working, and 20 percent are in school. This is not, for the most part, an idle population. But with California’s high housing costs, and median earnings for full-time working young adults in the state having dropped 11 percent since 1990, the economics of staying at home make more sense.

The collective worry found in headline portrayals of college-educated millennials returning home after school after having a hard time making it on their own obscures some serious issues of inequality, education, and job opportunities impacting a significant number of young Americans.

Fry found it was more revealing to break the demographic down by age range: 25 percent of people ages 25 to 29 live with a parent, up from 18 percent a decade ago, and 13 percent of people ages 30 to 34, up from 9 percent, with many struggling to find work, due in part to low educational attainment.

Every person’s story, and their housing decision, is an individual choice. But taken as a whole—looking at how a generation faces different economic challenges and expectations than their parents—a different narrative may emerge, one of caution, conservatism, and coming up without the same safety net.

“There’s a sense of feeling insecure about life, and not being able to know where you’ll be in five years,” Worth says about the results of her study. “It’s a sense that isn’t captured well in the numbers.”

Loading comments...